After the usual quota of bedtime stories, songs, sips of water and nighty-night kisses, our 4-year-old daughter, Eva, finally drifted off to sleep. My wife and I tiptoed from the tiny bedroom, left the door ajar to admit a slant of light from the hallway and then crept quietly downstairs to watch the new president deliver his first fireside chat.

It was February 2, 1977, a Wednesday. This was back when winter still felt wintry in southern Indiana, and our old house creaked from the cold. Ordinarily on a workday evening Ruth and I would have been heading toward our own bedroom to read for half an hour before sleep. But I was curious to hear what Jimmy Carter had to say, for there was much in his background and values that appealed to me. Like my father, he had grown up on a farm, and his Georgia accent resembled my father’s Mississippi drawl. He was an outspoken opponent of segregation, a rarity among white politicians from the South in those days. As a graduate of the Naval Academy and a former submarine officer, he knew enough about war to be wary of military adventurism, especially in the age of nuclear weapons and in the aftermath of our nation’s bitter defeat in Vietnam. Trained in science, a rarity among politicians of every stripe, he recognized that humans were upsetting the balance of life on Earth, a sobering truth that I had learned as a teenager from Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, and which, as a father, I worried about steadily.

I stoked up the woodstove in the living room, careful not to bang the firebox with the poker lest I wake the light sleeper upstairs. Then I opened the cabinet where we stored our black-and-white television, which we kept hidden from Eva except during the hour of PBS children’s programming we allowed her to watch on weekday afternoons. Our TV stealth might seem quixotic today, when screens are more abundant than butterflies, but in those pre-internet, pre-laptop, pre-cellphone days, parents could still shield young children from the electronic barrage. Ruth and I wanted to protect our daughter from all forms of pollution, including the violent cartoons and sugary ads aimed at kids from the device my father called the “one-eyed monster.”

Ruth sat on the couch with her head tilted back and eyes shut, weary from running our household, studying for her master’s degree in education and keeping up with a whirlwind 4-year-old. I sat down beside her, curled my arm across her shoulders and drew her close. I knew she was not only tired. She was also let down, as I was, from having learned earlier in the day that she had cycled through another month without becoming pregnant. We had been trying for the better part of a year to conceive a second child. Our decision to try for a first child had come slowly, in the face of misgivings shared by many of our friends, who had grown up during the Cold War with its threat of instant annihilation, and who also worried about the planetwide impact of a rapidly expanding human population. Eventually, Ruth and I had followed our affections, and no doubt our instincts, and she gave birth to Eva.

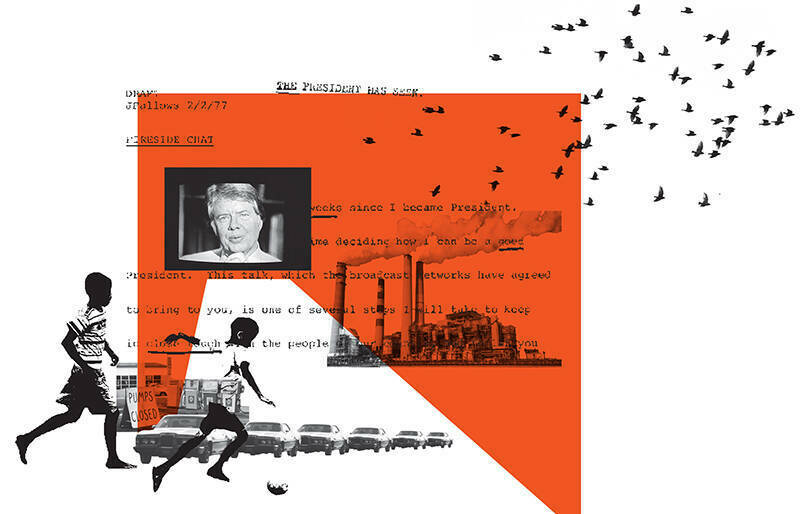

Our daughter was very much in my thoughts that evening, and so was the sister or brother we hoped to provide for her, as we watched President Carter deliver his “Address to the Nation on Energy.” He sat in an armchair next to a fireplace where low flames danced. Over the customary dress shirt and tie, he wore a cardigan that reminded us of the sweaters Fred Rogers wore on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, Eva’s favorite show. It pleased me, as a teacher and lifetime reader, that our new president had chosen to speak from the White House library, against a background of shelves crowded with books.

What he said surprised me. Only three years before, the OPEC oil embargo had reduced the supply of petroleum entering the United States, driving up prices and leading to long queues at gas stations. Many stations limited the number of gallons each customer could buy, and even with rationing some pumped their tanks dry. As the cost per barrel of oil doubled, then quadrupled, homeowners wondered if they could afford to pay their heating bills in winter. Since oil figured in the manufacture and transport of almost every product, inflation rose.

In light of that recent history, a politician wishing to curry favor with voters would have announced plans to defend us from runaway prices and reliance on imports by opening up public lands for drilling from the Arctic to the Gulf of Mexico, and he would have vowed to lower the cost of electricity by waiving clean air requirements for power plants. But instead of promising Americans more oil, Carter exhorted us to use less of it. He urged us to insulate our homes, drive smaller cars, rely more on trains and public transportation and develop renewable sources of energy such as solar power. Instead of promising to reduce regulations, he suggested new ones, such as imposing a luxury tax on gas-guzzling cars; and instead of vowing to reduce government bureaucracy, he proposed creating a new federal agency, the Department of Energy.

I listened to his words with a rising sense of hope. Here at last in our nation’s highest office was a champion of conservation instead of another cheerleader for consumption; here was a leader calling for us to preserve Earth’s abundance, and to do so for the sake of future generations. When the speech ended, my eyes were damp.

That evening came to mind lately when I found Jimmy Carter’s appeal for conservation listed on the Encyclopedia Britannica blog among the “Top 10 Mistakes by U.S. Presidents.” The author claimed that Americans had been depressed and irritated by the “Cardigan Sweater Speech,” and this widespread disapproval had played a part in denying the president a second term. Another blogger recently summarized public reaction by claiming, “Americans hated the speech and hated him for giving it.”

Troubled by these assessments, which ran so counter to my own, I looked up the text of the fireside chat to see what had moved me so deeply. I found the key to my response within the first few lines: “We must not be selfish or timid if we hope to have a decent world for our children and our grandchildren.” As a young father, fervently wanting a decent world for my child and for all children, I took that appeal to heart and listened sympathetically to everything that followed. My sympathy kept me from registering, or at least remembering, that as part of his plan for conserving oil, the president had called for increased reliance on nuclear power and “plentiful coal,” our nation’s most abundant fossil fuel. Had I paid closer attention to those proposals as I listened to the speech, I would have opposed them, and I would oppose them today. But what came through to me back then, what inspired me with hope and determination, was his call to make sacrifices for the sake of our children.

The press picked up on that word, “sacrifice,” which appears 10 times in the speech. That was 10 times too many in the opinion of the more cynical commentators. This Georgia peanut farmer — as pundits often referred to him when they wished to emphasize Carter’s naïveté — had failed to read the national character. America was the land of perpetual growth, the land where bigger meant better. Americans didn’t like being told that “Ours is the most wasteful nation on Earth.” Americans didn’t like hearing that “Those citizens who insist on driving large, unnecessarily powerful cars must expect to pay more for that luxury.” Americans resented being asked to use less oil, less gas, less of anything — the words “conserve” and “conservation” appear 11 times in the speech — and they didn’t want to see the president wearing a sweater in the White House because he had lowered the thermostat to 65 degrees. The cardigan made him look like Mister Rogers, for God’s sake, as if he were speaking to kids.

The pundits’ cynical response to the fireside chat has proven more prophetic than my hopeful one. Far from conserving petroleum, today the U.S., with just over 4 percent of the world’s population, accounts for more than 20 percent of global oil consumption, devouring this nonrenewable resource at a rate of 20 million barrels per day. President Carter’s fear was that we would run out of oil; the fear of climate scientists is that we won’t run out soon enough. They warn us that if we burn all the known reserves, we could trigger disastrous levels of global heating. Undeterred, the major oil companies, here and abroad, keep drilling for more.

The heat-trapping properties of carbon dioxide were first documented in the 1850s. A century later, in 1957, researchers for Humble Oil (later renamed Exxon) published a paper arguing that the burning of fossil fuels was increasing the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. A 1968 report to the American Petroleum Institute predicted that this increase in atmospheric CO2 could cause icecaps to melt and sea levels to rise, with unforeseeable impacts on marine life. In 1978, a scientist working for Exxon submitted a paper to the company’s management committee entitled “The Greenhouse Effect,” warning that an emissions-driven rise in global temperatures could disrupt agriculture by altering patterns of rainfall and drought. In 1982, an internal Exxon primer warned that continued burning of fossil fuels could lead to “potentially catastrophic events.” Alarmed by the threat these findings posed, not to the planet but to their profits, Exxon and other major oil companies formed the Global Climate Coalition in 1989, and under cover of that benign title they set about casting doubt on climate science, lobbying against legislative efforts to reduce carbon emissions and funding politicians who would keep the game going.

I’ve given the briefest summary of this disturbing history here, but you can find it thoroughly documented in dozens of books and hundreds of investigative articles published over the past 10 years. A friend of mine who knows the history told me about attending a daylong meeting that brought together climate activists like herself with oil company executives in an effort to find common ground. By the end of the day she had grown angry, because it was clear to her that the executives in their thousand-dollar suits were merely going through the motions, acknowledging the crisis without committing to any actions that might curb emissions. At the end of the meeting, as my friend was heading back to her car, she caught up with one of the CEOs in the parking lot and stopped him to ask, “Do you have grandchildren?” The man’s face hardened. “Don’t try that on me,” he told her. “I know all your arguments, and none of them matter, because this country runs on oil. If you stand in the way, you’ll get crushed.”

Perhaps the CEO has no children or grandchildren who will suffer from climate chaos after he is gone; or perhaps, if he does have offspring, he counts on being able to insulate them from harm with layers of money; or perhaps, like a number of celebrity plutocrats, he imagines they might flee to another planet. In any case, he made it clear he won’t let concern about future generations force him to question how he earns his millions or how his company garners its billions.

I don’t wish to single out the oil industry for blame, although I believe it has a lot to answer for, nor do I wish to demonize the man whom my friend accosted. I bring up this story to raise the moral issue implied by my friend’s challenge: What are we willing to change about the way we lead our lives in order to reduce the damage, and therefore the suffering, we are passing on to our children and their children and to all the generations that will come after them? If the answer is, we will change nothing — if we refuse to sacrifice any convenience, comfort, habit, profit or pleasure — then our descendants will have reason to despise us as we despise the owners of slaves for their poisonous legacy of racism.

Americans resented being asked to use less oil, less gas, less of anything — the words ‘conserve’ and ‘conservation’ appear 11 times in the speech — and they didn’t want to see the president wearing a sweater in the White House because he had lowered the thermostat to 65 degrees.

If you trace “sacrifice” to its roots, you will find that it originally meant the killing of a person or an animal to placate a deity. Human sacrifice was practiced in many ancient cultures, across Asia, Africa, the Near East and Mesoamerica, most notoriously among the Aztecs, whose priests butchered thousands of victims, many of them children and infants, to propitiate the sun god. Closer to my Midwestern home, evidence of extensive human sacrifice, mostly of young women, has been found in the Mississippian culture site known as Cahokia, across the river from St. Louis. It’s tempting to think that children and young women were favored choices for victims because they were the least able to fight back.

I first encountered the idea of human sacrifice when I was 12, on my initial cover-to-cover reading of the Bible. In the 22nd chapter of Genesis, I came upon the harrowing story of Abraham and Isaac. God says to Abraham, “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains that I shall show you.” Abraham obeys. He travels to the mountain, lays wood for a fire, places his bound son atop the wood and then takes a knife to cut the boy’s throat. At the last moment, God sends an angel to call off the murder, declaring that Abraham has passed the test and proven his faith. God also provides a ram, which is snared in a nearby thicket, to substitute for Isaac as the burnt offering.

As a boy, I could not imagine my father obeying such an order, not even from the ruler of the universe. Now, as a father myself, I cannot imagine worshiping any deity that would ask a parent to sacrifice a child. Biblical commentators have sought to justify God’s command and Abraham’s obedience in various ways, none of which I find convincing. However one interprets the story, it raises the question of what deities or idols we worship that might lead us, wittingly or unwittingly, to sacrifice our own children — not on a blazing pyre but on a baking Earth.

I am writing this essay in the summer of 2021, deep into the second year of the coronavirus pandemic. Alongside news of hospitals and morgues overwhelmed by victims of COVID-19, the media have been filled with reports featuring the word “record”: record heat waves, droughts, floods, glacial melt, intensity of hurricanes, coastal storm surges, coral bleaching, frequency of tornados, water rationing, electricity outages, crop failures, loss of wildlife, collapse of ocean fisheries and other signs of environmental upheaval. Fleeing this havoc, record numbers of refugees are on the move, unsettling every place where they seek asylum. These disasters, caused or amplified by global heating, were projected to arrive in the 2040s or later, but they assail us now. And climate models tell us the hazards will only get worse; how much worse depends on how quickly and decisively we curb greenhouse emissions.

More than half of the carbon released by the burning of fossil fuels in all of human history has occurred since Jimmy Carter gave his fireside chat. Over 85 percent has been released since 1945, which happens to be the year I was born. In a single human lifetime, we have more than doubled our population, ransacked the planet for raw materials and burned the bulk of the fossil fuels that had accumulated over millions of years. Within three score and ten years we have made Earth a less hospitable home for life. We did so not deliberately or malevolently but heedlessly. The only antidote for carelessness is to exercise greater care, and we might begin with caring for children.

When I was growing up in rural Ohio, I had a schoolmate who told me how, near the end of the month, when money ran out and food ran low, at suppertime his mother would pretend she wasn’t hungry, say she had a headache or an upset stomach. His father was away in the Navy, which left five of them at the table, his mother and four kids. She would serve everyone else, then take only a small portion for herself or nothing at all. My schoolmate was the oldest child and knew very well what she was doing, for she claimed a lack of appetite at the same time each month, as regular as the new moon. Many of us, possibly all of us, would do the same, if need be, to keep our children fed. What are we willing to do to keep our children safe?

A week or so after the night of Jimmy Carter’s fireside chat, Ruth conceived our second child, Jesse, who arrived that November. And so we had two reluctant sleepers, two beggars for stories and songs, two eager, curious, vulnerable kids to care for. Eventually, Jesse and Eva grew up, left home and became parents in turn. Today when I read the president’s speech, I do so with the perspective of a grandfather, which is why I am especially moved by a passage on the final page: “We’ve always wanted to give our children and our grandchildren a world richer in possibilities than we have had ourselves. They are the ones that we must provide for now. They are the ones who will suffer most if we don’t act.”

Those of us most responsible for destabilizing Earth’s climate have not acted with enough speed and dedication to spare children from suffering. They are growing up in a world that is hotter, harsher, more prone to extreme weather, less rich in wildlife and natural beauty, than the world into which we were born. None of us intends to hurt children, but that is the net effect of our collective behavior. Although we all contribute to this planetary unraveling, our contributions vary greatly from nation to nation, community to community, household to household, person to person. The poor have much less impact on the health of the planet than the rich do, and individuals have less impact than governments or corporations. But however mighty or modest our power, every choice we make, every action we take, either adds to the damage or aids in the mending. The children are watching, and they will remember which path we choose.

Scott Russell Sanders is a distinguished professor emeritus of English at Indiana University and the author of more than 20 books of fiction and nonfiction, most recently The Way of Imagination: Essays (Counterpoint Press, 2020).