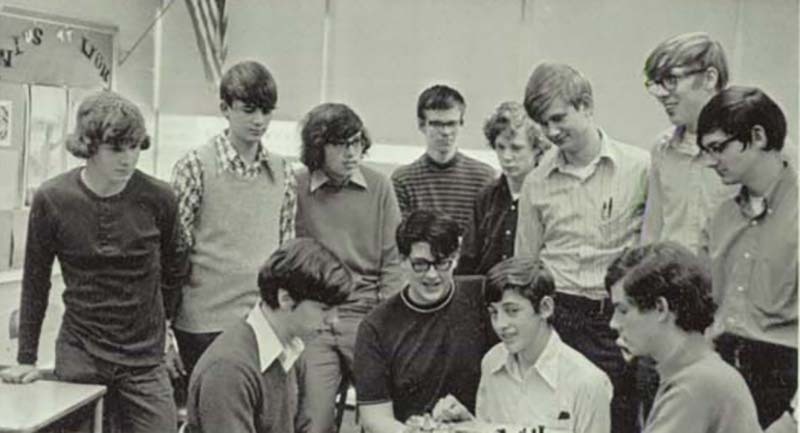

Lanzinger, standing third from left, and Newcomer, standing second from right, were chess club teammates who went on to create iconic arcade games.

Lanzinger, standing third from left, and Newcomer, standing second from right, were chess club teammates who went on to create iconic arcade games.

In the golden age of the video arcade, John Newcomer ’77 and Franz Lanzinger ’77 created games filled with colorful characters and flashing screens that attracted players like moths to a coin-operated flame. Though they were classmates in high school and at Notre Dame, neither knew the other had gone into the gaming industry until their work started gaining attention.

“I think I got a call from you out of the blue, and you were talking about how you were into arcade games,” Newcomer says to Lanzinger as the two reminisce during a joint Zoom interview. “I thought ‘Wow, what a weird coincidence.’”

Newcomer joined Williams Electronics, a prominent video game manufacturer, in 1981 as a lead game designer. Soon after being hired, he pitched a “treasure chest” of ideas, including one for what became the popular arcade game Joust. In it, a humble ostrich (or stork) assumes the role of a mighty steed, on the back of which a miniature knight armed with a lance takes flight, fighting off enemy knights and villainous buzzards. The game was among the first to popularize a two-player format, allowing competitive or cooperative play.

Some at Williams Electronics were skeptical during Joust’s development. At the time, spaceship games such as Defenders dominated the market. But Joust was well-researched, Newcomer says. He looked into people’s common dreams and superpower wishes; flying was a common denominator.

A marketing tip from Stan Lee helped, too. When the comic book legend visited campus, Newcomer, an avid collector in college, asked Lee how to create a memorable character. Keep it simple, Lee said, to allow for word-of-mouth advertising.

With that advice in mind, Newcomer ditched his mythical main character and decided on the ostrich. “I said, ‘OK, people will remember ostrich,’” he says. “They won’t remember the weird-ass name that I originally had.”

Lanzinger created an arcade classic of his own. Joining Atari in 1982 as a software engineer and game designer, he designed and programmed Crystal Castles. The game follows Bentley Bear, a satchel-clad character that players guide through a world of 3D mazes, shiny gems and evil obstacles.

“Throughout most of the project, it was kind of me debating with myself . . . putting on my designer hat and programmer hat,” he says. “It came down to trying stuff — and playing it.”

Crystal Castles was originally set in space, but a discussion among those working on the game steered it toward a fairytale theme. “We kind of invented all that in one meeting,” Lanzinger says, “and then it just evolved from there.”

At South Bend’s Clay High School, many of Lanzinger and Newcomer’s interactions were on opposite sides of a chessboard. They were two of the chess club’s “top boards” their senior year, Newcomer says, and often played during an honors history class they shared. While attending Notre Dame, the two lost touch. Lanzinger, originally from Innsbruck, Austria, pursued a degree in mathematics. Newcomer, a Granger, Indiana, native, studied industrial design.

Reflecting on those formative years, they commiserate in an email exchange about a chess club yearbook photo.

“Some of the geek aura dissipated in college and after,” Newcomer says.

“I truly have my classmates at Notre Dame to thank for helping me become a more normal person in just a few years,” Lanzinger adds.

Lanzinger’s passion for the arcade started young. He recalls coming up with video game ideas at age 10. While working as a scientific programmer before joining Atari, he would spend nights at the arcade. “I played all the games, every single one that came out,” he says. A favorite was Centipede, on which he set a world-record high score in 1981.

Newcomer, who designed toys and games after college, saw a “clear path to coin-op” as the popularity of arcade games surged in America during the early 1980s, when the industry was valued at $35 billion — nearly $120 billion in today’s dollars. His focus on creating game ideas led him to Williams Electronics, where he conceived Joust and stood by his creation against an influential naysayer.

Bill Herman, the manager of Mother’s Arcade in Chicago — a prominent testing site for emerging games — “absolutely slaughtered the game” when Williams’ president asked him to analyze it. “He said, ‘This is all wrong, it’s not gonna work,’” Newcomer recalls. “I just looked at him and said, ‘I’m right. He’s wrong.’” The game was released in 1982 to great acclaim, and Herman wrote a letter to the president of Williams apologizing for his misjudgment.

Despite his confidence, Newcomer did not expect Joust to reach such heights of popularity. “It was kind of surreal,” he says of the success of the game now enshrined in the International Video Game Hall of Fame.

Crystal Castles, released in 1983, was another big hit — winning accolades its creator also did not see coming. “I wish I could have anticipated at least some of it,” Lanzinger says. “I would’ve done a much better job preserving the history of it.”

After Crystal Castles, Lanzinger developed games for home consoles until leaving the industry, going on to play the piano — a childhood hobby — as an accompanist for choirs and singers. He’s now retired. Newcomer “got into mobile games from the ground floor” and today consults for a mobile gaming company.

Before smartphones offered a handheld buffet of such games, these high school chess club competitors thrived in the arcade era, earning the enchantment — and the quarters — of enthusiasts with the whirs and colors and challenges of the worlds they created.

Kate Ross, a senior American studies major and journalism minor, was this magazine’s summer intern.