The phone rang while I was having dinner alone. Kathy was at her daughter’s house. The caller was the lady from the symphony where Kathy and I had ushered on Sunday. “I understand there was a problem with one of the ushers on Sunday,” she began. I knew what she meant. I had to tell her Kathy has dementia, and this would be the last time — after 15 years — that we would usher. We would do it no more.

And so another border had been crossed. Like all serious diseases, dementia is a disease in which, over time, the sufferer crosses one border after another. The first one was the day she had to retire suddenly because she could no longer remember how to do her job. Without warning she came home from work one day, wept, and never went back. That was nine years ago.

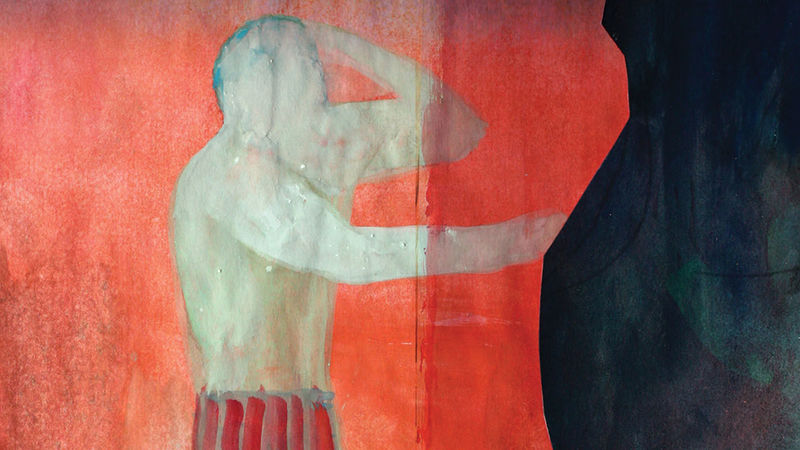

The next border was on a bleak November day nine months later when a tester/therapist sat in a room with Kathy, her children and me, and explained that Kathy had Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia. There was no way to know which form, short of an autopsy. From now on Kathy would be crossing borders out of her native country — her very self and all she has known her whole life — into one alien landscape after another, geography she does not want to enter and from which she cannot retrace her steps home. Though I (and occasionally her daughter and son) would be physically present, Kathy would be crossing these borders alone.

To visualize these borders, place a pencil point on the center of your thumbprint. Now slowly move the pencil point out toward the edges of your thumb and you will cross one whorl after another. Each whorl takes you farther from the center. Eventually you leave the thumbprint altogether. In dementia each crossing takes you farther from home and into the geography of the unknown.

For nine years now Kathy has been crossing these borders alone. There was the day she first got lost driving home from her daughter’s, a route she had taken hundreds of times. A man at a gas station called to tell me where she was, and I drove out to lead her home. Then the day that she was about to drive to her daughter’s and held out her hand with coins and asked me to count out how much was there in case she needed it as she was driving. She didn’t know the names or values of any of the coins. Then the day not long after when I took away her car keys.

There was the day I asked her who I was and she could not tell me my name or our relationship. Then the day I knew that she didn’t know her own full name, only the word Kathy. And the day I noticed she no longer knew the names for common things and could rarely make a coherent English sentence. We were having lunch on the patio and I pointed to the sky, the grass, the house, the table, my hand, arm, nose, ear and asked what these things were. She could command none of these words. They had fled and would never return. These words were now like the last sight someone has before going blind, the last sound one hears before going deaf, the last thing a soldier’s feet feel before stepping on an IED.

She crossed another border the day she didn’t recognize her daughter and son as her children. They were just people who were very nice to her, people who smiled at her and said nice things, and she beamed back her enormous smile of gratitude. Another border was crossed the first time I asked her where we lived, and she didn’t know the country, state, city, street or house number.

The first time she could no longer be in a room alone, even to watch TV, because she had to be with me every minute. The first time I noticed that when she sat in a room with me as I worked, she was constantly removing napkins she had hoarded in her pocket, rearranging them, putting them back in her pocket, then taking them out again and rearranging them.

The first time she fell asleep in her chair watching me write on my computer and I took care to be especially quiet, not for the sake of her sleep but, like mothers everywhere, for the sake of my own private time.

The first time I noticed she could no longer read. I pointed to a sentence printed in large type and asked her to read it to me. I was hoping she could fill her empty hours — and so many of her hours are empty — with simple books, but she could not read the sentence. The first time I saw that she could no longer write. The first time she did not know how to sign her name. No matter how many times I wrote out her signature in front of her and asked her to repeat what I had done, she could not do it.

The first time she did not recognize the myriad, small Love Is cartoons we used to cut from the Chicago Sun-Times, show to each other and then Scotch-tape to the inside of her closet door. The cartoons eventually overlapped each other, making the door nearly invisible: line drawings of a boy and a girl, to which we added our own words, calling each other Boy and Girl. “Boy lights up my life,” she wrote on one. “Would never have seen Paris without Boy,” she wrote on another. “Girl is beautiful,” I wrote under one drawing. Now she no longer knew who Boy and Girl were, could not read the writing and did not know why the cartoons were on the door. And she did not remember Paris — nor Ireland, New York, Maine, Hawaii or anyplace else we had ever been.

The first time I had to help her use the toilet. The day she began using Depends. The first time I had to help her take a bath. The first time she put her pajamas on over her street clothes to go to bed.

The first time she said to me one evening, “I want to go home” — among the few sentences she still speaks — and I said back to her, “Honey, you are home.” That scene now plays out nearly every evening. Sometimes she says, “No, my home is far away,” and she gestures with her hand, waving to a place beyond our walls. “No, honey,” I say, “_this_ is your home. You’re home now.” I ask her to describe the home she wants to go to, but she can’t, so we argue back and forth till finally I convince her she is home. Sometimes it takes many minutes for me to win. I say win rather than persuade because I’m not always sure I persuade. Sometimes I think I merely wear her out. Other times I win in one sentence. I tell her: “I love you.” If she believes me — and she usually does — she says, “Oh, thank God,” in a voice filled with emotion.

But always, in this now nearly daily dialogue, I wonder about this word home. What home is she looking for? The home in which she was the mother of three young children? The home of her daughter, where she goes for a day and a half each week? The home where she lived as a child with her mother, brothers, busia, jaja and beloved Aunt Florence (none of whom she remembers any more)? Or is her nervousness something like the static that still exists from the Big Bang that began the cosmos? Is she experiencing the longing for home that has existed inside every human breast since the dawn of time?

I am reminded of an anecdote Susan Cheever tells at the beginning of her wonderful memoir of her father, John Cheever, Home Before Dark. One evening after a long summer’s day, her father was standing outside the house under a big elm tree when her younger brother Fred came back from playing with friends. He was worn out and when he saw his father standing there, he ran across the grass and threw his little body into his father’s arms. “I want to go home, Daddy,” he told him, “I want to go home.” Of course he was home, but that didn’t make any difference. We all want to go home, her father would say whenever he told this story, we all want to go home.

Perhaps this is the home my wife wants to go to, the home we all want to go to. When you suffer from dementia, you are never home, you are always across the border in a strange land, and where else would you want to go — especially when night has fallen and it is dark outside your windows — than home? When I tell my wife she is home, I am telling her the truth, but only half the truth. Yes, this is home. The other half I don’t tell her is: she’s not here. She now lives across a border in no man’s land, and she will never be home again.

I too have crossed borders. There was the first time I wondered how — how does she live in such a state of unconsciousness with a face always breaking into sunshine at the sight of a child or a dog or at the sound of a kind word spoken to her? How does she do that? I wondered that thought for the first time some years ago. Now I wonder it every day.

The first time someone asked me, “How’s Kathy?” and I knew those words meant something different from what they used to mean.

The first day I realized this disease was going to be at the center of my life from now on. I could read a book, watch a movie, talk with a friend, write an essay, read my email, but I would never again know the innocence of life without this disease.

The first time I noticed that I was sometimes speaking to her in simple truncated sentences, skipping articles and pronouns and anything nonessential. The first time I noticed she was always standing or sitting in the way when we were in the office or kitchen, forcing me to constantly reposition her in the room so I could work. The first time I noticed I was in a quiet state of rage for no special reason, a rage that now visits several times a week. The first time I noticed I was asking, “Are you okay?” every 10 minutes because she was always silent and I wanted to be sure she wasn’t angry or depressed. The first time I realized we would probably never have a real conversation again, and that for most of my hours I would be in solitary confinement.

The first time I wondered, Dear God, how long will this go on? Will I be able to last the whole way? And I did not know the answers to these questions. But these questions are always followed by the realization that my lot is easy compared to hers.

The first time I wondered: Will this happen to me too?

The first time I called her Saint Angela because, despite dementia, her soul was so kind, innocent and gentle that I thought of her as both a saint and an angel. This went on for several years, but a year or two ago I stopped saying it. Then one night not long ago, after I had been reading for a while, I turned to look at her. We were lying on top of the bed in our clothes. I said, “Let’s go watch TV,” something she loves to do. And in that moment of looking at her grateful face, seeing how good, kind and gentle she is, the words came back to me. I called her Saint Angela. In that moment I joined her on her side of the border. We were together. She wasn’t alone.

The first time I cried when I realized my beloved was disappearing into a strange country and would not be coming back. The first time I cried when I turned from my computer to ask how she was and saw her rearranging the napkins from her pocket. The first time I cried when I saw her eyes pleading with me not to be angry with her for needing help to do some ordinary action. The first time I cried when she said “thank you” for no other reason than that I had spoken to her. The first time I cried when we sang a 50-year-old love song together and I knew those were among the last coherent sentences she could utter any more. The first time I wanted to cry but didn’t when she went off to her daughter’s, leaving me alone.

For me the saddest border of all is what I have come to call the Inevitable Border. It is a border I believe every long-term caretaker crosses, willingly or not, consciously or not. This is the crossing in which the caretaker begins a life separate from the person he or she cares for. In the beginning the caretaker doesn’t allow himself to be aware of the separate life he is beginning. The guilt would impale him.

- Related articles

- Thank You

My own separation began by more vigorously pursuing my passion for reading, writing, movies and golf. At first I didn’t know I was doing this; much later I knew I was saving my life. And Kathy didn’t mind. She was happy to sit in the same room with me as I wrote or read, and happy to ride in a cart and watch me golf. At first I did this without thinking, the way runners put one foot in front of the other and swimmers stretch out their arms and pull water. They do this without thinking because if they think, they will collapse or drown.

I especially stole every moment I could to write. And the woman I cared for was often the person I was writing about — as I am doing right now. In my writing I was carrying on a relationship with the woman she once was as well as the woman she is now, living in a land I cannot cross into, but whom I can see across the invisible border. Without realizing it at first, I was taking up a separate life in my writing.

It is no secret that when a member of a couple develops dementia, the couple’s friends begin to fall away or at least make appearances less often. And something like solitary confinement becomes a way of life. So I have taken every opportunity to deepen relationships with others whose souls are most alive to me. Most alive to me is a phrase I don’t remember using before in describing friendships; I do so now, deliberately, for it is this phrase that I have come to realize characterizes all true friendship. The more solitary confinement became a reality, the more I longed for deep relationships: people who were truly alive to me, people who saw me, people who cupped their hands beneath my being and held me, if only for a moment. And I was willing to do the same for them. Taking care of someone with dementia has taught me that we must love and be loved — or we collapse and drown.

This Christmas I crossed a border in my annual Christmas newsletter. In the last paragraph I thanked some people whose genuine and unexpected smiles of welcome touched my soul regularly during the year. Among them were two women in my church congregation. On a whim several weeks after Christmas, I decided to give copies of the newsletter to these women. I had not used their names, so I wrote in the margin: “You are one of these people. Thank you so much for touching me with your smile.”

The week after I gave it to one of the women, she made a point of coming up to me before Mass and telling me how important my letter had been for her at that particular moment the previous week. She was implying that I had greatly helped her. She then asked to see some of the essays I had mentioned in my newsletter. The next week I gave her an essay and the following week she told me I was “transforming” her life. I was jolted because this woman is one of the most alive, welcoming and wholesome people I’ve ever known — vastly ahead of me in all these qualities.

Several weeks later I gave the letter with my marginal note to the one distributor of communion at Sheil Catholic Center who makes a point of radiating the joy of this sacrament with her smile. After Mass she came up to me and said my letter and note had made her cry. I was overwhelmed. Then she asked if she could see one of my essays, and the next week I brought her one.

In giving these two women my letter and my essays I was extending my soul to theirs. We would not likely become regular intimates, I knew, but we had touched each other’s souls, if only briefly. It was a small reprieve from solitude.

I also gave the Christmas letter to two of my Apple trainers who unfailingly welcome me to our personal training sessions as if I were long-lost family. I just wanted to say thank you to these men.

I would never have written the paragraph about welcoming smiles into my letter and never have given the letter to these people were it not for Kathy’s perpetual attitude of thanksgiving — she is always thanking me, even when I give her tasks to do — and the growing sense of solitary confinement her disease has caused. In handing out my letter, I was only reaching across the borders of my confinement.

I also sent my newsletter together with a personal letter to a woman I once dearly loved but hadn’t seen in 24 years. She lives in a distant state and, last I knew, was happily married. I didn’t think I’d hear back from her, but I wanted, at least by implication, to let her know what a wonderful person she had been. I couldn’t remember anyone in my life ever treating me kinder.

She did write back, by email. Her husband had also suffered from dementia, she told me, before he died of a stroke a little more than a year earlier. We have since exchanged weekly email letters of compassion and understanding. The ones I have received have been small miracles rescuing me from solitary confinement.

People who love each other — husbands and wives, parents and children, friends — cross borders throughout their relationships. If they are lucky, the borders are permeable and either person can cross back. For dementia sufferers the borders are not permeable. The crossings are one-way only. So each week I stand at another border waving goodbye to someone I love, and she doesn’t know I am waving goodbye. She just smiles back her enormous smile from the foreign country where she now lives — and says thank you.

One day I will turn to see her face, touch her cheek, hear her voice, and it will be the last time. I will not know it is the last time. Unpredictably, silence and stillness will have come to reign. There will be no face to see or voice to hear. Light will come in the window as it always has, gray or bright, and it will fall in the middle of an empty room.

Mel Livatino’s essays have appeared in The Sewanee Review, Writing on the Edge, River Teeth, Under the Sun and other publications. Four of his pieces have been named Notable Essays of the Year in Robert Atwan’s Best American Essays annual (2005, 2010, 2011, 2012). He is at work on two books: The Little Red Guide to Publishing Creative Nonfiction and God: An Inquiry, the latter about the existence and nature of God and evil. He lives in Evanston, Illinois.