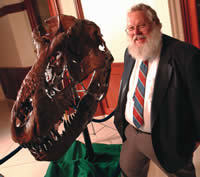

J. Keith Rigby Jr. never met a dinosaur he didn’t like. And over the course of his 34-year career as a paleontologist he met tons of them, literally. The associate professor of civil engineering and geological sciences, who died unexpectedly on November 5 at age 64, conducted archeological digs in Montana, Wyoming and China. At Notre Dame, he taught courses in physical, historical and environmental geology, sedimentation and stratigraphy. He received his doctorate from Columbia University in 1977 and joined the ND faculty in 1982.

In 1997, the ND scientist led a team that discovered a huge Tyrannosaurus rex fossil near the Fort Peck Reservoir in Montana, believed to be one of the largest specimens ever unearthed. While the discovery was noteworthy for its size alone, news coverage went viral when a local ranch family, falsely claiming ownership of the dig site on federal land, attempted to steal the fossil. Rigby received death threats, an FBI investigation ensued and stories appeared on CNN and in TIME, Newsweek and The New York Times.

A popular teacher with a booming voice and a knack for colorful stories and language, Rigby earned teacher of the year awards from the College of Engineering and Sorin Hall as well as the Distinguished Scholar Award from the College of Science. A devout Mormon, he was a master of the imaginative G-rated expletive. The Utah native was known, for instance, to voice his displeasure with someone by using a rebuke such as, “my sister’s black cat’s rear end” and other creative epithets.

In his later years, the father of six grown children sported a full, snow-white beard. With his ample girth, Rigby bore an uncanny resemblance to Santa, whom he delighted in playing for children during the holidays.

He is survived by his wife, Susan, ex-wife Virginia Peterson, and six children from the two marriages.

**

For nearly 50 years at Notre Dame, everyone from undergraduate science novices to senior chemistry faculty knew that when you ran into the inevitable stumper in thermodynamics and needed clear, incisive help, it was time for a chat with Robert G. Hayes. The Philadelphia native and professor emeritus of chemistry, who died in July at age 74, arrived on campus in 1961 and toiled here happily and almost exclusively until his retirement in 2009.

For years the pleasantly cynical Hayes taught huge sections of Physical Chemistry of Life Sciences — then required for medical school aspirants — and other courses in physical chemistry. Meanwhile, he defined collegiality for a generation of Notre Dame chemists, who found in him an unparalleled expertise in electron paramagnetic resonance, a sounding board for their own research ideas and a resource for challenges they faced in the classroom. Once, when a blackboard proof had failed to enlighten students, a colleague asked Hayes how he would explain that any number raised to the power of zero always equals one. Hayes suggested he have them take out their calculators and start punching numbers. “They’re not going to believe you,” he quipped, “but they’re going to believe their calculator.”

Hayes’ patience and curiosity applied to his avocations as an outdoorsman, photographer and student of languages, the last of which he was known to cultivate by sitting in on classes at Notre Dame. He is survived by his wife, Linda, and their five children.

**

When they say “their blood is in the bricks” of those whose dedication and service built Notre Dame and made it great, they’re talking about people like Herbert E. Sim. The Austrian-born macroeconomist, who retired in the early 1990s after 35 years on the business faculty, many of which he spent as chair of what was then the Department of Finance and Business Economics, died last spring in Tucson, Arizona. Sim was 87.

Former students, like Barry Keating ’67, the Jesse H. Jones Professor of Finance, may remember their Money and Banking professor as a quiet, steady, dedicated presence in the classroom, qualities that along with a reputation for absolute discretion and a deep institutional memory made Sim a trusted adviser to many at the University, including the administration. When, as president, Father Ted Hesburgh was hatching plans to create the University’s first endowed chairs, he called Sim for insights. And when a donor approached the College of Business asking how to help, Sim’s ideas took shape in the O’Hara lecture series that brought some of the finest minds in economics to campus, including John Kenneth Galbraith, Charles Schultze and Robert Heilbroner — an important step toward the global mindset of today’s Mendoza College.

It seems Sim rarely spoke of his U.S. Army service in World War II, when his fluent German served him as an interrogator of Nazi POWs and earned him a Bronze Star. A private man who let others do the talking and went home for lunch nearly every day, Sim, also a classical music and opera buff, diligently pursued his intimate and evolving grasp of the financial sector throughout his academic career. Ask him any arcane question, Keating recalls, and “you’d be an expert by the time he’d finished his 10-minute explanation of it.” Preceded in death in 2009 by Sylvia, his wife of 63 years, Sim is survived by their five children.