Donald Sporleder, professor emeritus of architecture, was a man of active interests long after his retirement from full-time teaching in 1998: parks and nature conservancy, biking and walking paths, river recreation and historic preservation, to name a few. He was an enthusiastic volunteer for community organizations that furthered those causes.

“Don was such a force in the community, he was never out of sight. Not only was he a great teacher, but he was an example of how to fix the world,” says Alan DeFrees ’74, the James A. and Louise F. Nolen Professor of Architecture.

After service in the U.S. Army, the Illinois native earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in architecture from the University of Illinois. He started his career in Chicago, then taught for several years at his alma mater before joining the faculty at Notre Dame in 1963. The family settled in Roseland, within walking distance of campus, and Sporleder immersed himself in campus and community life. He had a tradition of inviting students and colleagues to picnics in his backyard, and his electronic mailing list, through which he distributed architecture news to friends and colleagues, was legendary.

Sporleder served as acting director of the School of Architecture’s Rome Studies program in 1970-71, and he returned to Italy for tours of duty in the 1980s and ’90s. His architectural firm developed master plans for universities in Ireland, Thailand and Pakistan. Closer to home, projects across the Midwest included numerous residential works, design of the Architecture Building at Ball State University and redevelopment of a former brewery into the 100 Center in Mishawaka. In 1988, the governor of Indiana named Sporleder a Sagamore of the Wabash for his services to the state.

He was a fellow of the American Institute of Architects. In 2020, he received a gold medal from the institute’s Indiana chapter, its highest honor.

Sporleder died May 14. He was 92.

Seamus Deane had an air of authority, delivered in the classroom and in public lectures with a brogue befitting the subject of his erudition and imagination — Irish literature and culture.

Deane’s association with Notre Dame dates to 1973, when he taught for a semester at the University. Two decades later he became a fixture on campus as co-founder and chair of the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies.

“The presence of Seamus Deane helped Notre Dame build the top program of its kind in the world,” said the institute’s other co-founder, Christopher Fox, professor emeritus of English.

Three poetry volumes published between 1972 and ’83 established Deane as a leading Irish voice, though with the fame of his lifelong friend, Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney, Deane wrote that he became “Seamus eile — Irish for ‘the other Seamus.’ A nice qualifier. Otherhood via brotherhood.”

In Irish literary scholarship during his lifetime, there was no other Seamus. Raised in a Catholic nationalist family amid sectarian division in the Northern Ireland town of Derry, Deane would study how Irish novelists, poets and playwrights grappled with the nation’s tumultuous history. His insights formed the basis of three works of critical analysis in the 1980s that made him a prominent public intellectual. And he served as general editor of the three-volume Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, published in 1990, his academic magnum opus.

Deane further demonstrated his facility with language in a celebrated novel of his own, Reading in the Dark, shortlisted for the 1996 Booker Prize.

For all his literary accolades, Deane maintained his childhood love of soccer. According to The Irish Times, a friend said “Seamus was the best footballer in St. Columb’s, then he fell in with the wrong crowd and became a poet.” He did fall in with the poets, said his son Ciarán, one of Deane’s five children, “but he never turned his back on football. It was central to his life and to our lives together,” just another of the diverse subjects that seeded his fertile intellect.

Deane died May 12 in Dublin. He was 81.

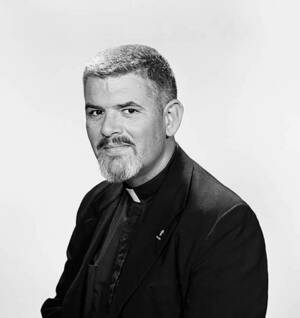

Bob Kerby’s Civil War classes were legendary. They were as popular with science and business students as with history majors. They were acts of 20th-century performance art, as the gravel-voiced, brush-cut professor reenacted battles, brandished weapons, sang war songs, told stories and provided detailed accounts of both famous and little-known events in that epic watershed of American history. Arriving an hour before the classes he taught in a large, fourth-floor classroom in the Main Building, he pinned up flags and copies of old newspapers. On a bank of slate blackboards, he drew intricate maps with different hues of colored chalk to depict military movements and battle lines. Generations of students called it their favorite class and the bearish, lovably gruff professor their best teacher.

Robert Lee Kerby ’55, ’56 M.A. was born June 26, 1934, in New York City. He studied history at Notre Dame, then joined the U.S. Air Force and piloted both cargo planes and gunships, serving in the Far East with combat experience in Laos and Vietnam. During his years with the military, he earned Silver and Bronze stars, a Distinguished Flying Cross and a Purple Heart. Critical of the escalating war in Vietnam, Kerby was honorably discharged and earned a doctorate in American history from Columbia University in 1969.

His office there was once vandalized by anti-war protestors who had misinterpreted his short hair, military service, classes on warfare and pilgrimages to Civil War battlefields as a fondness for military action. Kerby’s experiences in Southeast Asia had not left him; one of his goals was to educate students on the follies of war.

He joined Notre Dame’s faculty in 1972, wrote two books on the Civil War and taught his popular classes until he retired in 1998. In 1970, with the approval of Pope Paul VI, Kerby, a husband and father, was ordained a priest of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church by Patriarch Maximos V Hakim in Heliopolis, Egypt. Father Kerby founded St. John of Damascus Melkite Greek Catholic Church in South Bend and served as its pastor for 37 years.

He died April 14 at age 86.

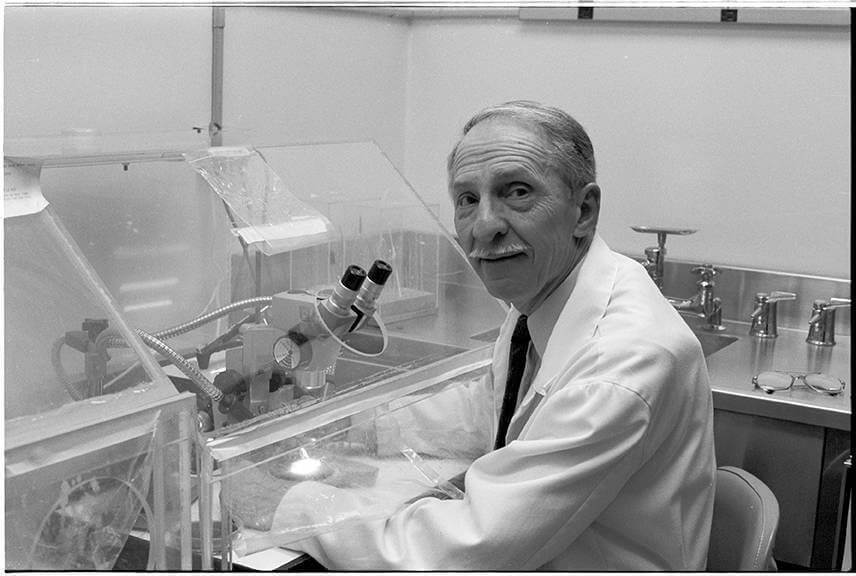

For more than three decades, most Notre Dame pre-medicine and biology majors took the embryology course taught by Kenyon S. Tweedell. For some, the class charted the course of their future careers.

Among Tweedell’s students was future Princeton University professor Eric Wieschaus ’69, who, with two co-recipients, won the 1995 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for “discoveries concerning the genetic control of early embryonic development.” Wieschaus later recalled how he first saw developing frog embryos in the laboratory while taking Tweedell’s courses and was immediately hooked. “I had found my scientific mission,” he said.

Born and raised in Illinois, Tweedell served in the U.S. Navy on a minesweeper in the Pacific Ocean during World War II. After the war, he earned his bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees in developmental biology at the University of Illinois. He taught at the University of Maine for several years, then joined the Notre Dame faculty in 1958, where he would teach and research for another 34 years. His investigations of tumors in frogs were supported by grants from the American Cancer Society.

Every summer for decades, Tweedell traveled to the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, where he studied regeneration in small marine animals. Those summers on Cape Cod produced many happy memories for him and his family. “I always got the summer fishing report from him,” says Jack Duman, a professor emeritus of biology and longtime friend.

Tweedell became the unofficial historian of the biological sciences department, authoring a 1999 book, The Lineage of Biological Sciences at the University of Notre Dame.

He was an enthusiastic birder and fisherman, a member of the St. Joseph’s Catholic Church choir, a gardener, a runner and a regular in the Joyce Center’s faculty workout room well into his 90s.

He died March 30 at age 97.

When studying international migration, Jorge A. Bustamante ’70M.A., ’75Ph.D., believed in field research.

He’d watch people arrive at the Mexico-United States border, approach them and ask for interviews. For his doctoral dissertation on Mexican immigration and capitalism, he experienced the migrant journey himself by crossing the border without papers.

Bustamante, the Eugene P. and Helen Conley Professor Emeritus of Sociology, helped advance discourse about migration around the world. His advocacy for immigrants’ rights worldwide led to his nomination for the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize by his native Mexico.

Born in Chihuahua, he earned a law degree from the National Autonomous University of Mexico in 1959, then studied sociology and anthropology at Notre Dame. There he became the first graduate student of the revered

Professor Julian Samora, a mentor to dozens of Mexican American scholars who later taught at universities across the U.S. Bustamante joined the Notre Dame faculty in 1986, became a fellow at the Kellogg Institute for International Studies and served as associate director of the Institute for Latino Studies.

Bustamante’s command of Spanish put interview subjects at ease. “They immediately opened up to him. They trusted him. They felt comfortable talking to him,” recalls Gilberto Cárdenas, a professor emeritus of sociology.

Bustamante authored more than 200 publications on international migration and on the Mexican population living in the U.S., and his expertise was often sought by major newspapers and television news organizations.

He founded El Colegio de la Frontera Norte in Tijuana, Mexico, and served as its president until 1998, then continued his teaching and research.

In 1997, Bustamante was appointed to a new, five-member United Nations committee to study the relationship between international migration and human rights worldwide, and his work for and with the UN would continue through 2011.

Bustamante died March 25 in Tijuana. He was 82.

Janice Poorman ’88M.A. ’96Ph.D. was a dedicated teacher and a fiercely loyal friend, passionate about her work and her Catholic faith. She had a talent for helping her students find the right ministry placements to help them reach their potential.

A systematic theologian by training and a professor of the practice in the Department of Theology, Poorman was director of formation and field education for the Master of Divinity program, which trains seminarians and lay ministers for pastoral work. She served for 28 years in that role and in various administrative and leadership positions at the University, including as an associate dean of the Graduate School.

As a natural collaborator in her core work on faith formation, Poorman helped to create what is now the Echo Graduate Service Program, in which students earn a master’s degree in theology while serving in a Catholic parish or school, as well as the popular Notre Dame Vision summer conferences for high school students and youth and campus ministers. She regularly presented at retreats and facilitated among countless appreciative students and workshop participants the art of theological reflection.

Poorman grew up in Arizona, California and Illinois, and fell in love with teaching at a young age. “She didn’t just teach the faith. She lived it from the heart. And she taught her students and colleagues to do the same,” says Colleen Moore ’97, ’04M.Div., the director of formation for the McGrath Institute for Church Life and Echo program director.

Poorman died March 10. She was 68.