When Thomas Gordon Smith was a graduate student of architecture at the University of California, Berkeley in the 1970s, he brought his talents as a trained artist and a contrarian’s taste for the classical into his studies of a curriculum that was decidedly modernist. One of his professors, curious but unenthusiastic, framed the tensions Smith was creating as a question: “What is it you want to do — applied archaeology?”

Within a few years, Smith’s designs, derived from the architectural traditions of ancient Greece, were already arresting the attention of theorists and practitioners at the highest levels of his new profession. He put a belated answer to that lingering question into his correspondence with one of them: “I’m striving,” he wrote, “for a richness of meaning.”

It would be difficult to overstate the impact since that moment that Smith, the chair of the Notre Dame School of Architecture from 1989 to ’98, who died June 23 at the age of 73, and whom The New York Times once called — with begrudging respect — one of “Architecture’s Young Old Fogies” — has had upon the revival of classical architecture in the United States.

Here is one measure: When Notre Dame’s provost, Timothy O’Meara, handed over the Bond Hall keys to the young professor who’d taught at UCLA and Yale, Smith took responsibility for an architecture program that by some accounts was about to close its doors. Soon, and with O’Meara’s firm support, he separated the department from the College of Engineering and reorganized it as a freestanding school. He instituted a classical curriculum over the objections of some fraction of the school’s mostly modernist faculty; secured the accreditation of the graduate program for the first time in the University’s history; and established the undergraduate program, in the estimation of the president of the National Architectural Accrediting Board, as one of the top 5 five-year programs in the country.

All had not gone smoothly. At least one faculty member fled from Smith’s new vision and many older students wanted no part of it. Smith would transition to full-time teaching and private practice after nine years at the helm. But in the 32 years since his arrival, Notre Dame has become a laboratory and proving ground for the New Classicism — the “Athens of the new movement.” Today it is “pumping graduates into the world with these highly unusual but very sought-after skills,” which include freehand drawing and watercoloring, notes New York-based architect Mark Foster Gage ’97.

Architecture critic David Brussat quantifies Smith’s impact this way: “Some 1,200 classicists formed at Notre Dame have expanded the number of classically oriented architecture firms from a mere handful to hundreds around the world today.”

Born in Oakland, California, in 1948, and grateful to his Catholic faith for “liberating” him from what he considered the minimalist creative constraints of modernism, Smith made international waves at the 1980 Venice Biennale with the classical façade he created to front a gallery of work he’d completed as a Rome Prize fellow. Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote Smith off as “a kind of naïve or folk classicist,” but the influential Yale art historian Vincent Scully opined that Smith already stood “alone in America . . . in the haunting aura with which he can endow his images.”

Warned by renowned architect Robert A.M. Stern that his reputation meant he could no longer “just work for somebody,” Smith opened his own firm, which over the decades would produce important sacred buildings such as Our Lady of Clear Creek Abbey in Oklahoma — designed to meet the Benedictine monks’ request for a structure that would last 1,000 years. Museum work and civic buildings included the classical galleries of the American Wing of New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and a civic hall for Cathedral City, California.

Visitors to Notre Dame may see his signatures in the Bond Hall renovation, Carole Sandner Hall and the mausolea of Cedar Grove Cemetery. And private residences Smith designed in California, Illinois, Indiana, North Carolina and Wisconsin include homes he built for himself, his wife, Marika, and their six children.

One of those homes, Vitruvius House, a Roman temple-inspired structure that Smith completed in 1990 in an otherwise unassuming residential neighborhood of South Bend, paid homage to the Roman architect who “encouraged the emperor Augustus to revive correct forms and principles of Greek architecture,” Smith explained. Reliefs sculpted for the home’s single-story wings narrate the heroic feats of Hercules; a fresco inside depicts Vitruvius and another Roman builder to represent the creative tension between rule and invention that Smith felt defined his own practice — and what he hoped to impart to students.

“The whole idea of doing something original is so old now,” he told the Times in 1995. And yet, he would later insist: “This isn’t paint-by-number architecture, I’m constantly inventing.”

To students he was “Vanilla Thunder,” the tweedy, glasses-and-bow-tie wearing professor with the gentle manner and the shock of white hair who championed the principles that attracted them to the discipline. “Students and employees always knew to expect incisive comments and even sharp criticisms of their work,” John Haigh ’98, ’04M.Arch wrote in a tribute to his former boss. “But he would follow up these initial volleys with congratulations for their effort, some fatherly wisdom, and words of encouragement.”

Author of two books, Smith is the subject of one, Thomas Gordon Smith and the Revival of Classical Architecture, authored by University of Miami architectural historian Richard John. But the best measure of his impact came in a 2016 interview, in which he acknowledged the transformation at Notre Dame as novel — but not unique. “In fact,” he said, “such classical programs have multiplied to become, oddly enough, what you might say are the avant-garde.”

While studying in Germany as a young man, Randy Klawiter developed a fascination with the Austrian novelist and biographer Stefan Zweig. It became a lifelong enthusiasm.

Zweig was one of the most translated writers of the 1920s and ’30s. Klawiter became a Zweig expert, a member of the International Stefan Zweig Society who amassed a collection of more than 500 books by and about the author.

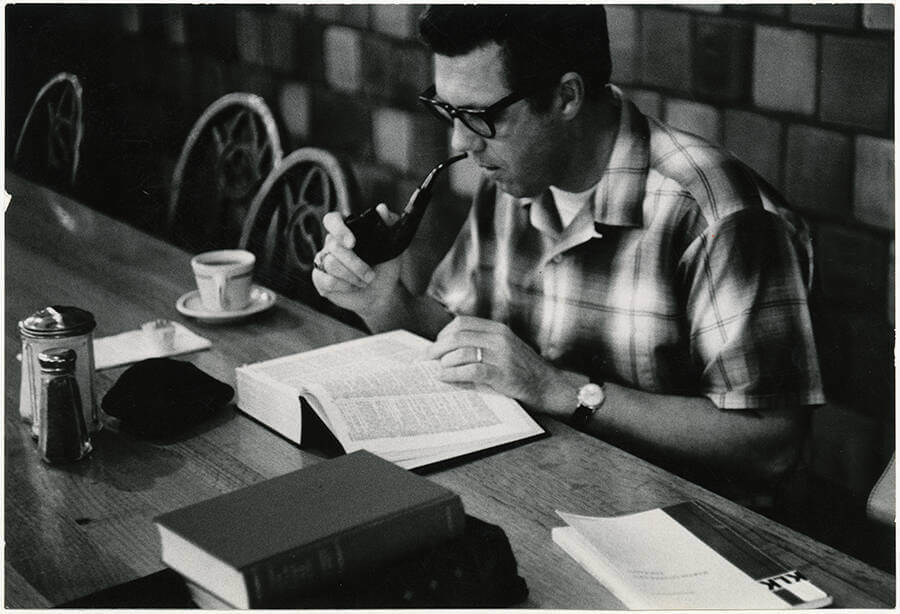

A longtime professor of German, Klawiter was known for his sense of humor, his kindness and his understanding of human nature. Born and raised in Grand Rapids, Michigan, he earned a bachelor’s degree in European history at Aquinas College and his doctorate at the University of Michigan. He served in the U.S. Army for eight years, including a period in Germany in the 1950s. He joined the Notre Dame faculty in 1960 and retired in 1995.

Klawiter was the go-to person in the Department of German and Russian Languages and Literatures on matters of style and word choice in writing. He freely offered his proofreading skills on numerous projects. His stylistic elegance was legendary, says Albert Wimmer, an associate professor emeritus of German.

In retirement, Klawiter created the Zweig Wiki (zweig.fredonia.edu), an extensive online bibliography of Zweig’s work based at the State University of New York at Fredonia. That labor of love involved collaborating with people around the world who provided details about books, articles, recordings and other materials related to the author.

Klawiter and his late wife, Marilyn, with whom he raised seven children, were active members of Sacred Heart Parish, where he volunteered on parish committees and served for decades as a Eucharistic minister and lector. He enjoyed family gatherings, swimming, walking his dogs and listening to Mozart in his office.

He died July 19 at age 90.

Ava Preacher was known for spontaneous gifts: vegetables and herbs from her garden, a silk scarf from a trip abroad, time for a student or an important cause.

A professional specialist emeritus, Preacher served more than two decades as an assistant dean in the College of Arts and Letters, advising students there on their academic paths as well as those from across the University who were thinking about going to law school.

“She had this marvelous way of being able to connect with the students. They loved and trusted her,” says JoAnn DellaNeva, a professor of Romance languages and literatures who worked with Preacher for decades.

A voracious reader who admired artists, poets and great thinkers, Preacher had an outgoing and cheerful personality. She grew up in Iowa, earned a master’s degree in comparative literature at the University of Iowa and studied film in Paris. She joined the faculty at Notre Dame in 1985, initially teaching in what was then the Department of Communication and Theater. After a term as director of the gender studies program, she moved to the arts and letters dean’s office, where she built strong bonds with mentees over the next 25 years and earned numerous awards for her teaching and academic advising.

A valued leader of the campus community, Preacher had an encyclopedic knowledge of University policies and how they had changed over the years, a talent that served her — and the school — well during her stints on the Notre Dame Academic Council, the Faculty Senate, the gender studies executive committee and other campus bodies to which she devoted her time.

Preacher died on July 14 at age 67. She is survived by her wife, Coleen Hoover, retired coordinator of the University’s Creative Writing Program, and their four children.

Law professor emeritus J. Eric Smithburn was a big man, in size and personality. Standing 6 feet, 4 inches tall, he was a scholar of family law and a compassionate advocate for disadvantaged children and families.

“He was full of life and energy. He was always laughing,” says law professor Jay Tidmarsh ’79, a longtime colleague and friend.

A native Hoosier, Smithburn earned bachelor’s, master’s and law degrees from Indiana University. A favorite early job was teaching history at Crispus Attucks High School, at the time an all-Black high school in Indianapolis.

Athletics were a central part of his life. Smithburn played basketball in high school and rugby as an adult, including a tour on a men’s team that competed internationally in the early 1980s. In 1969, he signed a contract to play for the Indianapolis Capitols, a team in the pro Continental Football League, but canceled it to go to law school.

After practicing law and serving as a judge in Marshall County, Indiana, Smithburn joined the Notre Dame Law School faculty in 1978. In addition to family law and juvenile law, his academic interests included evidence and appellate review.

Smithburn directed the Law School’s summer program in London from 1984 to 2000, teaching at Notre Dame throughout the regular academic year. He was a senior judge in St. Joseph County Probate Court and continued to serve on the bench after retiring from Notre Dame in 2015.

In addition to numerous law articles and textbooks, Smithburn wrote The Illustrated American Tourist Guide to English English, a book about British slang, and co-edited Lizzie Borden: A Case Book of Family and Crime in the 1890s.

Smithburn was called to the bar in England and Wales, a rare distinction for a foreign attorney. That honor left him “chuffed to bits” — extremely pleased — to borrow some of the British slang that delighted him.

He died June 18 at age 76, survived by his wife, Aladean, and their two children.