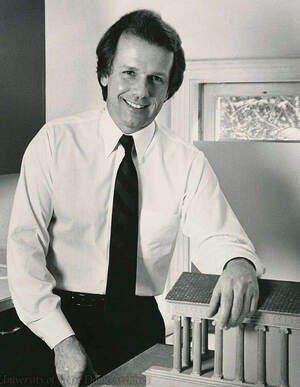

Robert L. Amico had an early interest in art and design. It became the foundation for his life’s work as an architect, artist, designer, professor and principal of a firm.

A professor emeritus and former chair of the School of Architecture, Amico died July 26. He was 84.

Born and raised in Chicago, Amico was a first-generation college student. Trained in Beaux Arts and modern design, he studied at the University of Illinois and Harvard University, then practiced with International Style design firms in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Chicago. After 12 years at Illinois, where he was a professor and chair of architecture design, he was hired to lead Notre Dame’s architecture program in 1978, serving as its chair for 11 years.

A strong advocate of freedom of expression, Amico led the expansion and development of architecture faculty and facilities and strengthened the school’s connections to Rome and Chicago. Under his leadership, the Department of Architecture became the School of Architecture and established a master’s degree program.

Amico demonstrated his deep commitment to his students during the many hours he spent with them in studio. “He played the role of editor to the students’ designs” and pushed them to expand their intellectual boundaries, said Michael Lykoudis, the former Francis and Kathleen Rooney Dean of Architecture. Amico’s faculty office was always elegant, clean and minimalistic — a nod to his architectural sensibilities. “It could have been designed by Mies van der Rohe,” Lykoudis said.

Amico retired in 2010 and soon established Amico LLC, Art and Design, a studio producing conceptual artistic works. He was a member of the American Institute of Architects and participated as a volunteer and board member with nonprofit organizations focused on the arts and mental health.

Amico enjoyed Italian cuisine, handball, time with family and vacationing in Florida. He is survived by three children and six grandchildren.

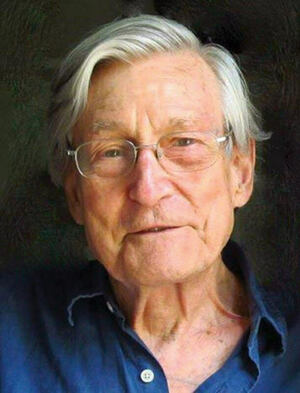

To draw the attention of distracted students, Thomas R. Swartz once walked on his hands while presenting a classroom lecture. He crafted a course called Gourmet Economics that included an economics lesson followed by a meal he prepared with other professors or with students in the class. Long before Zoom, the educational innovator and longtime professor of economics videotaped his lectures for students’ use.

Swartz died July 19. He was 84.

“Tom was one of the most gregarious individuals you could ever meet,” says Frank Bonello, a professor emeritus of economics who knew Swartz for more than 50 years. The two men collaborated on multiple editions of a book titled Taking Sides: Clashing Views on Economic Issues.

Swartz was born in Philadelphia, but his family soon moved to rural Pennsylvania, where he attended a two-room schoolhouse for a time. He excelled at swimming and diving, went to La Salle University on an athletics scholarship and later claimed that his entire postsecondary education at Ohio State and Indiana universities cost $25.

In 1965, Swartz joined the Notre Dame faculty, where he spent the next 45 years teaching everything from introductory courses to interdisciplinary seminars. His academic specialty was urban economics. Swartz created and ran a Notre Dame summer program in London and was active in the Faculty Senate, serving as that body’s president. In 1992 he received the Rev. Charles Sheedy, CSC, Award for excellence in teaching, the highest teaching honor in the College of Arts and Letters.

He and his wife, Jeanne Jourdan ’75J.D., married each other twice: both times on August 12, first in 1961 and again in 1992.

An active volunteer in Democratic political campaigns, Swartz assisted local and state government leaders with issues related to urban economics. He enjoyed golfing and racquetball. In retirement, he made his home in Cass County, Michigan, where he served on the local planning commission, founded a swimming camp for grade school students and was elected a commodore of the Diamond Lake Yacht Club.

He is survived by Jourdan, five daughters, eight grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

James L. Merz ’59 was already an internationally recognized scholar of optoelectronic materials and devices when he returned home to Notre Dame in 1994 to direct a team of researchers investigating quantum cellular automata, a transistorless approach to computing.

The Frank M. Freimann Professor Emeritus of Electrical Engineering, Merz died June 22 at age 86. He had served Notre Dame as a vice president for graduate studies and research, dean of the Graduate School and interim dean of the College of Engineering.

Anthony Hyder, a professor emeritus of physics, described his friend as a man of enormous energy, a gentleman through and through. “I don’t think I ever heard him raise his voice,” Hyder said. “He respected people, and they respected him.”

After earning a bachelor’s degree in physics, Merz went to Germany as a Fulbright fellow and completed master’s and doctoral degrees at Harvard. He joined Bell Laboratories to investigate the optical properties of compound semiconductors, then spent a year as a visiting lecturer at Harvard before returning to Bell.

As a professor of electrical engineering at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Merz founded its Center for Quantized Electronic Structures before Notre Dame asked him to bring his experienced leadership to a young, dynamic materials science and nanoelectronics group.

Merz viewed graduate instruction and research as two sides of the same coin. He helped the University create interdisciplinary centers and institutes where students could work alongside faculty in other fields and prepare for potential careers in industry as well as academia. “He recognized that graduate students not only contribute to a research agenda, but they make great role models for undergraduates,” Hyder said.

In 2001 Merz created Lumen, an early online magazine that showcased Notre Dame research, scholarship, creativity and teaching. He received an Alexander von Humboldt Research Award in recognition of his lifetime achievements in science and engineering and an honorary doctorate from Linköping University in Sweden. During his career, Merz published more than 400 papers and held five patents.

Merz loved God, his family, Notre Dame, Cape Cod and traveling. He is survived by his wife, Rose-Marie, and four children.

Roger Valdiserri ’54 was once described as “the Forrest Gump of college athletics” because “if it was big and it was important in the last 50 years, he was somehow there.” Joining Notre Dame’s athletics department in 1966, he would chair the NCAA public relations committee, spend nine years alongside Father Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, and others examining the proper role of intercollegiate athletics on the Knight Commission, work 22 consecutive Final Fours, nine Super Bowls, three Olympic Games and one World Cup and be inducted into a half-dozen halls of fame.

Yet Valdiserri is best known for his 29 years as Notre Dame’s sports information director. “No one ever understood Notre Dame better or represented it better,” legendary football coach Ara Parseghian once said of him. “Roger’s importance to the University is immeasurable.”

He was “the gold standard in the field of media relations,” said Malcolm Moran, who covered Notre Dame athletics for three decades for The New York Times, Chicago Tribune and USA Today.

In an era before “brand” and “marketing” and “promotions” were common jargon, Valdiserri was a practitioner, acting as the liaison between Notre Dame athletics and a large and ardent press corps that followed the Irish locally and nationally, in broadcast and print, by personally answering a multitude of requests and elevating the school’s reputation off the field and on. His foremost rule: “Don’t ever lie.” He explained, “If you lie, you’re of no good to your organization, because you have no credibility. If you don’t tell the truth, you lose your integrity; and if you don’t have integrity, you have nothing.”

Valdiserri saw the athletes as representatives of the institution and became a trusted adviser to Jim Lynch ’67 and Alan Page ’67, Joe Montana ’79, Raghib “Rocket” Ismail ’94 and others.

When Valdiserri saw Joe Theismann ’71 (pronounced THEES-man) as a scrawny freshman, he told him to change the pronunciation of his surname to rhyme with Heisman. He did, finished second in the Heisman voting in 1970, and the quarterback’s family also adopted the change.

His many friends remember Valdiserri as a great storyteller with a quick wit, gentle nature and keen insight. His sense of Notre Dame and his savvy and perceptivity earned him a place in upper-level University conversations beyond athletics until his retirement in 1995. Despite his slight build, he was one of the giants whose good work helped create the modern Notre Dame. He died June 2 at age 95.

In his lifetime as a painter, Douglas Kinsey had more than 70 one-man shows in the United States as well as in England, Sweden and Japan. In addition to this solo work, the Notre Dame art professor collaborated with friends and fellow artists on assorted projects and illustrated two dozen books. Even more than the purposeful dedication he brought to his art, generations of his students remember Kinsey himself as a kind, gentle, generous and idealistic mentor.

The recipient of several prestigious educational honors, including Notre Dame’s Rev. Charles E. Sheedy, CSC, teaching award, Kinsey opened his studio and home on Notre Dame Avenue to the students he counseled in art and life. “He was truly dedicated to his students,” recalls ceramics professor Bill Kremer, a longtime friend. When grading student work, Kinsey “would type out a letter to each student, explaining the grade and his understanding of the work. He had a large student following, and they would come visit him for years after graduation.”

Born in Oberlin, Ohio, and a graduate of Oberlin College and the University of Minnesota, Kinsey infused his artistic vision with influences from his Quaker heritage.

Perhaps his best-known work depicts refugees and the victims of war, injustice and natural calamities. Using photographs of real-life events — border crossings, displacements, innocents caught in gunfire — Kinsey created impressionistic studies of people gripped by political upheaval, infusing his subjects with integrity, pathos, respect and an appeal to shared humanity.

“My art is not about outrage,” he once said. It is about “the drive to carry on in spite of adversity” and a “reminder of the spirit that binds us together.”

Kinsey joined the Notre Dame faculty in 1968, retired in 1999, and continued to paint and exhibit and participate in departmental critiques of student work. He died at home May 21 at age 88 and is survived by his wife, Marjorie Schreiber Kinsey.