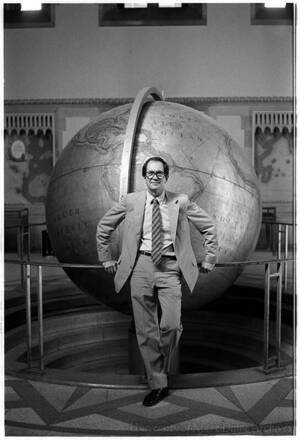

Few have woven Notre Dame into the local community as broadly, successfully and sensitively as Jay Caponigro ’91. His legacy includes the Robinson Community Learning Center, of which he was founding director; the Moreau College Initiative, which sends Notre Dame faculty to teach in the Westville Correctional Facility; and the Teachers as Scholars program, which brings local educators into classes taught by Notre Dame faculty and staff. Few areas — geographic, educational, religious or cultural — were not impacted by Caponigro’s soft-spoken but strong sense of justice, his servant leadership and his easy manner of forging relationships across seams in the social fabric.

Whether leading as an elected member of the South Bend school board or engaged with the mayor’s anti-violence commission, Caponigro, as Notre Dame’s senior director of community engagement, was a model of amiable goodwill and effectiveness. Under his guidance, the Robinson Center opened its doors in a repurposed grocery store south of campus in 2001 as a collaboration between the University and Northeast Neighborhood. Some 500 students volunteer there annually, providing learning opportunities that span generations, including the Robinson Shakespeare Company, a Lego Robotics team and the Take Ten conflict resolution program, at the thriving community center now housed in a new facility adjacent to Eddy Street Commons.

A Chicago native, Jerome Vincent Caponigro was honored as a Notre Dame senior for exemplifying the University’s ideals through outstanding service beyond campus. After organizing farm workers in New Mexico and laborers in Texas, he returned to his old neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side as executive director of the faith-based Southwest Organizing Project. He joined Notre Dame’s Center for Social Concerns in 1999, his faith always central to how he worked and lived. He was a teacher and humble student of power in all its expressions and a studied advocate of Catholic social teaching.

“Jay was a builder,” said Michael Hebbeler, a program director at the center, “and he understood the processes to get there — whether it was drawing up a floor plan for a house project, negotiating among decision-makers in the city or building relationships with University faculty and inviting them into community projects. But while his work was strategic, it was never transactional. His approach was one of invitation.”

Despite his service on multiple boards, his civic involvement and nightly meetings, Caponigro was fully a father, coaching youth sports teams, driving the John Adams High School band trailer and attending Mock Trial competitions. He was a goalie in an adult hockey league and a regular in a South Bend baseball league. He built not only alliances but also furniture, a model train set in his basement and other home renovation projects, often showing up at friends’ houses with his red toolbox in hand. He relished time spent at his woodsy retreat in Wisconsin and was devoted to his wife, Lyn, and their family.

A final gift may have been the grace with which he lived his final 14 months with pancreatic cancer. He died May 11 at age 54.

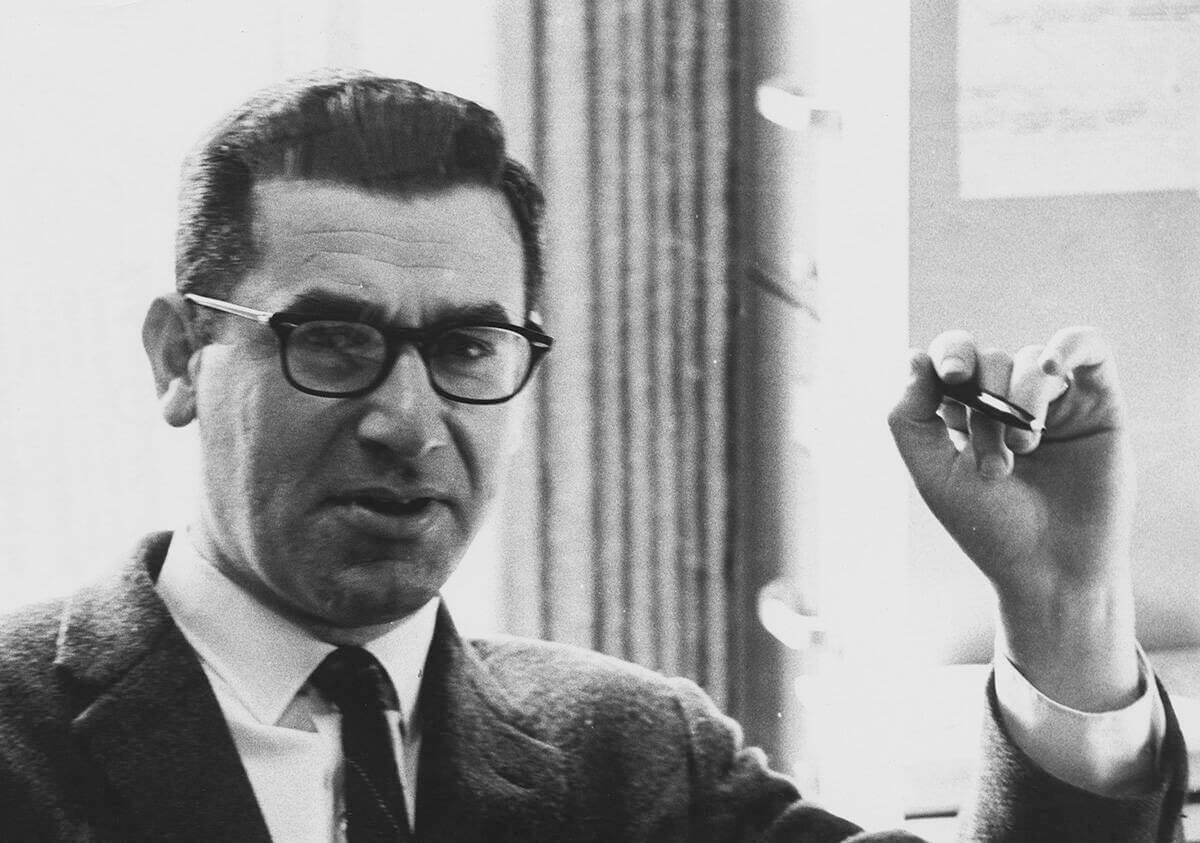

Jay P. Dolan pioneered a distinctive approach to the history of Catholicism, focusing on parishioners rather than the clergy. Founder of the University’s Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism, he became one of the nation’s most influential historians of the faith.

Dolan, a professor emeritus of history, died May 7 at age 87.

Born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, Dolan earned a bachelor’s degree from St. John’s Seminary, was ordained a priest in Rome in 1961 and served in parishes in the Diocese of Bridgeport. He earned a licentiate in sacred theology from the Pontifical Gregorian University and master’s and doctoral degrees from the University of Chicago.

Dolan joined the Notre Dame faculty in 1971, soon left the priesthood and married shortly thereafter. In 1975, he launched the American Catholic Studies Newsletter and persuaded the University to create what is now the Cushwa Center. He served as the center’s inaugural director until 1994, guiding research and publication projects, developing grants and fellowships, and hosting lectures and conferences — most notably the semiannual Seminar in American Religion.

Dolan advanced the development of social history, the study of ordinary people and their religious communities — or, as he often put it, “the people in the pews” — embedding the Catholic experience in the larger American story. His major work in this field, published in 1985, is The American Catholic Experience: A History from Colonial Times to the Present. He edited several others, including the two-volume The American Catholic Parish and a three-volume history of Hispanic Catholicism.

In the 1990s, Dolan turned to the study of Irish America. He retired from teaching in 2003 but continued as an active scholar, publishing The Irish Americans: A History in 2008. He authored many other works of religious and social history.

Dolan taught undergraduates in classes such as The Irish American Experience, directed doctoral students and held visiting appointments at Princeton University, University College Cork, Boston College and the University of San Francisco.

He never took himself too seriously. “He would always tell me how important it was to have a life outside of work. That’s not something a lot of Ph.D. supervisors will say,” said Kathleen Sprows Cummings ’94M.A.,’99Ph.D., the Rev. John A. O’Brien Collegiate Professor of History and American Studies. Cummings stepped down in June after 11 years as Cushwa director.

Dolan mentored many younger historians. “I remember as a Ph.D. student saying to him that not enough had been written about women in the Catholic Church, and he said, ‘You’re right. You do it,’” recalled Cummings, the author of two major books on the subject.

A superb golfer and devoted lay minister to the homeless, sick and dying, Dolan led both the American Society of Church History and the American Catholic Historical Association as president and served on the historical committee that helped to plan the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration.

Dolan’s wife of more than 40 years, Patricia McNeal Dolan, died in 2018. He is survived by two children and two grandchildren.

Michael M. Stanisic encouraged his students to use the mechanical principles and mathematical tools they learned in the classroom to build functioning machines. They took to the task with enthusiasm.

Hundreds of student-built robots and off-road vehicles came to life during the 30 years that Stanisic served as adviser for Baja SAE, an intercollegiate engineering design competition, and the 12 years that he led the Robotic Football Club.

Stanisic, an associate professor of aerospace and mechanical engineering, died April 11 at age 65.

“He was a bit of a grizzly bear on the exterior, but he was a huge teddy bear on the inside,” said Michael Seelinger ’94, ’97M.S., ’99Ph.D., the Dunn Family Teaching Professor of Engineering, who took two of Stanisic’s courses as an undergraduate. Stanisic became Seelinger’s mentor, then a close colleague and friend.

Born in Lafayette, Indiana, to parents who had immigrated from Serbia after World War II, Stanisic trained at Purdue University and joined the Notre Dame faculty in 1988. He reveled in his work, often declaring that he had “the best job in the world.”

An expert in robotics, Stanisic authored and co-authored textbooks and numerous papers on kinematics, a branch of mechanics that deals with mathematical descriptions of motion. He also invented and patented new types of robotic joints. A gifted teacher, he won many awards for instruction and advising, including the Joyce Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching — three times.

Stanisic’s favorite form of transportation was a fixed-speed bicycle, even in winter. In fine weather, he liked to take a spin in one of his classic cars: a ’67 Malibu Chevelle or a ’68 Triumph TR250. He enjoyed music, attending live performances, gardening — tomato cultivation was his specialty — and cooking, particularly Serbian recipes. He hosted dinner parties and hog roasts and volunteered to serve meals at Hope Ministries. Every winter he fermented homemade sauerkraut.

A devout Orthodox Christian, Stanisic served several terms as president of Saints Peter and Paul Serbian Orthodox Church in South Bend. He is survived by three daughters, two sisters and a brother.

The academic passion of Lee A. Tavis ’53 was studying how multinational companies could adapt to help the poor more effectively. He traveled to some of the poorest regions of the world to observe conditions firsthand.

On one trip to northern Kenya, Tavis and his companions stayed several days with religious sisters. The convent’s conditions were simple — the visitors bathed in rainwater — but it didn’t stop Tavis from helping nearby villages get needed medicines.

Tavis, the C.R. Smith Professor Emeritus of Finance, died April 4. He was 91.

Born in Bismarck, North Dakota, Tavis was a soloist in his high school choir, played in a band called The Little Acorns and enjoyed horseback riding. At Notre Dame, he studied business and was a member of the inaugural Irish Guard in 1951. Then known as the Irish Piper Unit, members in those early years marched and played the bagpipes at football games.

After college, Tavis served in the United States Navy. His first assignment aboard the USS Begor was a humanitarian mission providing safe passage to Vietnamese soldiers and civilians fleeing communist North Vietnam. He would serve as a Navy pilot for three years.

Tavis earned his MBA from Stanford University and a doctorate in business from Indiana University, then returned Notre Dame in 1976, where he would become the founding director of the University’s Program on Multinational Managers and Developing Country Concerns, write six books and teach courses in managerial finance, international financial management and international ethics. He also took on leadership roles in the University’s international programs, directing the MBA programs in Chile and the United Kingdom and serving as a faculty member at The University of Notre Dame Australia.

Tavis was widely respected for his work in advancing civil and human rights, especially in developing countries, said Rev. Oliver Williams, CSC, ’61, ’69M.A., a longtime friend and colleague. An outgoing man, Tavis also knew the value of quiet moments. “We worked hard together, but we would always have a nice glass of wine afterwards and relax,” Williams recalled.

Tavis often reached out to new faculty hires to help them get acclimated to campus, and by the end of his courses, his students often became friends, Williams said.

Tavis’ numerous teaching and administrative awards included the James E. Armstrong Award for distinguished service to the University. He is survived by Sparky, his wife of almost 70 years, and their three children, seven grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren.

Barth Pollak was known for his enthusiastic and engaging teaching style. A professor emeritus of mathematics, he died February 17 at age 94.

Born in Chicago, Pollak studied mathematics at the Illinois Institute of Technology, received his doctorate from Princeton University with the help of a National Science Foundation fellowship, then served on the mathematics panel of the Scientific Advisory Board for the National Security Agency.

Pollak taught math at IIT and Syracuse University before joining the Notre Dame faculty in 1963. He spent 37 years teaching and conducting research on classical groups, the arithmetic theory of quadratic forms and algebraic number theory before retiring in 2000, receiving the College of Science’s Shilts-Leonard award for excellence in teaching along the way. He also served as assistant department chair and director of the University’s Innsbruck program.

“Barth and I were colleagues and friends for six decades,” said John Derwent ’55, ’63Ph.D., an associate professor emeritus of mathematics. “He loved mathematics and teaching and hated administration.”

In addition to his academic work, Pollak enjoyed classical music and jazz, learned ancient Greek, and was a regular swimmer and an avid reader of history. Helen, his wife of 67 years, died in 2022. He is survived by a son, a daughter and two grandchildren.