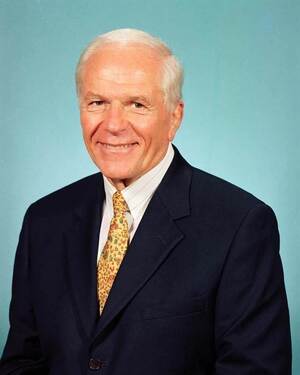

Bill Sexton was a heavyweight wrestler at Ohio State University. The Columbus, Ohio, native would also earn three degrees there, including a master’s degree in industrial management and a doctorate in administrative management and behavioral sciences. He learned his lessons well and at Notre Dame was a beloved practitioner in the art of human relations.

William P. Sexton joined the Notre Dame faculty in 1966 and would become one of the business school’s most popular professors, receiving the Best Teacher Award four times and filling lecture halls with students drawn to his expertise and engaging classes. When it was pointed out that virtually all his students received A’s, the professor quipped, “I only teach the best.”

Sexton’s academic specialty was human behavior in organizations, and his scholarship focused on organization, individual needs, conflict and the management of change. He taught in the College of Business for 40 years, even after his career took a radical turn in 1983.

That year, Sexton became vice president for University Relations, directing the University’s fundraising operation, the Alumni Association, international advancement, special events and several communications departments, including this magazine. Before retiring from that office in 2002, Sexton would oversee an impressive expansion of Alumni programming, establish a community relations office and direct two major development drives, including the Generations campaign that raised more than $1.1 billion before its conclusion in 2000.

For all his achievements, Sexton may be best remembered for the humanity he brought to everything he did. Those who knew him — from all walks of life — spoke often of how an encounter with him invariably lifted their spirits.

“Above all, Bill was a superior teacher,” says Dan Reagan ’76, who worked with Sexton for 17 years, including a decade as director of development. “Technically a specialist in organizational behavior, he was so much more than that. He was a mentor, coach, cheerleader, boss. How often do you find that? And he taught through word and example. As a result, the culture of our division, of our department, reflected that. We knew we were cared about, and I think that helped us care for each other. It was a special time.”

In 2002, Sexton was the first recipient of an award established in his name to recognize service to the institution by a nongraduate. That same year he was awarded an honorary Notre Dame degree.

Despite the demands of his vice presidency and his service on multiple local boards, Sexton was rooted in family. The father of six (one daughter and five rascal sons), he coached baseball teams, drove winners to Dairy Queen, taught his kids to fish and play golf, and told funny stories with a proclivity for exaggeration. A bench on campus dedicated to him and to Ann, his wife of 62 years, reads: “Parents wear no warmer scarf than their children’s arms around their necks.”

Whether along the Lake Michigan shoreline or at Land O’ Lakes, Wisconsin; Bonita Beach, Florida; or South Bend’s Blackthorn golf course, he bestowed love on those children (four of whom attended Notre Dame), 19 grandchildren, 15 great-grandchildren and especially Ann, whom he spotted at Mass one Sunday and on their first date told her they would someday marry.

He died October 17 at age 85.

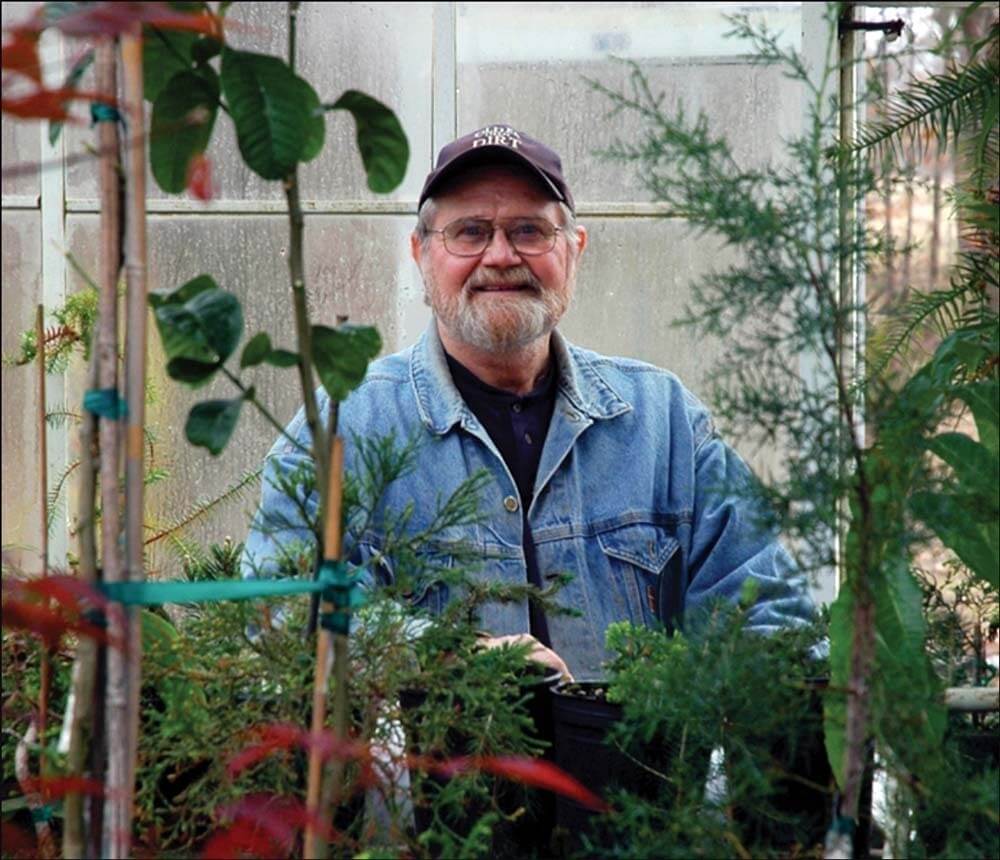

Tom Schlereth ’63 described himself as an “above-ground archaeologist.” The historian probed urban landscapes, the plantings of orchards, the design of houses and churches, and the artifacts, tools and belongings of a people for the intelligence these things confided about their past. The professor of American studies was a nationally known expert in material culture, and his classes opened students to new vistas on familiar ground. “Every feature of the landscape has a story to tell,” he once told a reporter. “I want to make driving and walking historical adventures.”

Schlereth had been a tour guide as a Notre Dame student. His appetite for Notre Dame history as revealed in its architecture, geography, archival documents and lore culminated in The University of Notre Dame: A Portrait of Its History and Campus. The 1976 book, which included some 430 photographs, maps, lithographs and drawings, served for decades as the definitive work on Notre Dame’s history. He would later produce monographs on the Main Building and the Basilica of the Sacred Heart.

Having joined his alma mater’s faculty in 1972 after earning a doctorate at the University of Iowa, Schlereth was the author of 15 books and 80 journal articles. In reviewing the scholar’s 1990 Cultural History & Material Culture: Everyday Life, Landscapes, Museums, Ann Gorman Condon of the University of New Brunswick wrote: “Schlereth’s message once again is celebratory. Readers familiar with this scholar’s previous work are well aware that over the past decade he has carved out a unique position within the material culture field. He is our chronicler, our bibliographer, probably our foremost advocate. At the same time, he is also our pied piper, a tunesmith whose siren song invites our diverse collection of researchers, curators, souvenir hunters, and museum managers to join hands with his and dance together.”

Schlereth died November 11, at age 82. He is survived by his widow, Wendy Clauson Schlereth, a longtime director of University of Notre Dame Archives, and their son.

Teaching was the primary focus of nuclear engineer John W. Lucey ’57, a member of Notre Dame’s aerospace and mechanical engineering faculty for nearly 40 years.

Born in Massachusetts and raised in part in Nebraska and New York, Lucey attended Notre Dame on a Naval ROTC scholarship, ran cross-country and track for two years and graduated with a degree in chemical engineering. He then served in the U.S. Navy and earned master’s and doctoral degrees in nuclear engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Back at his alma mater in 1965, Lucey would teach many of the College of Engineering’s courses in nuclear engineering before his retirement in 2004. His research spanned numerical methods, radiation shielding, energy conservation and educational technology.

In 1988, Lucey opened a door for undergraduate engineers long understood to be permanently locked by the college’s rigorous course requirements when he co-founded a summer program that, for the first time, permitted Notre Dame engineering majors to study in London. For more than a decade, he directed that summer program, which eventually expanded to opportunities during the regular academic year and in additional countries.

A faculty adviser for the student-run Notre Dame Technical Review, Lucey also recruited students to assist him with the Notre Dame Industrial Assessment Center, which analyzed energy use, conservation methods and savings opportunities for local small industries.

He loved opera, reading, travel, Notre Dame sports and the Boston Red Sox. His undergrad athletic habits persisted into his on-campus second life; he could often be found running inside the north dome of the Joyce Center to keep fit, or attending Mass inside the crypt beneath the basilica where he was a dedicated member of Sacred Heart Parish.

“I’d see him at Sacred Heart, always with a navy blue blazer, a tie and a smile,” said Joseph Powers, a professor of aerospace and mechanical engineering.

John Lucey died November 6 at age 88. Nancy, his wife of 55 years, preceded him in death in 2012. The couple is survived by four children, seven grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Robert Nelson ’64, ’66M.S. joined Notre Dame’s aerospace engineering faculty when the department was housed in the “aero shack,” a World War II-era Quonset hut that stood north of the Joyce Center. From that rickety facility, Nelson built an internationally recognized research program and wrote a popular textbook, Flight Stability and Automatic Control.

Nelson served on the Notre Dame faculty from 1975 to 2014. A professor emeritus and former department chair of aerospace and mechanical engineering, he died October 19 at age 81.

Nelson was mild-mannered and much beloved by his students, said Steven Batill ’69, ’70M.S., ’72Ph.D., a professor emeritus of aerospace and mechanical engineering. Batill recalled the time he and Nelson supervised an undergraduate Air Force ROTC student who had built a small airplane from plans and decided to taxi it around Green Field west of Notre Dame Stadium. “Bob and I had fingers crossed he would follow those directions” and not try to take off, Batill said. The day ended happily, with the student realizing the plane had been a good learning experience but was never going to fly — and the two professors sighing in relief.

Nelson grew up near the New Jersey shore and earned his doctorate at Penn State. He worked for several years in the U.S. Air Force Flight Dynamics Laboratory at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio, before returning to Notre Dame to continue his research, which concerned the aerodynamics and flight dynamics of missiles and aircraft. With a goal of developing safer flights, he conducted experiments analyzing potentially destabilizing airflows.

After the aero shack was decommissioned in 1991, Nelson continued his work in the up-to-date facilities of the Hessert Laboratory for Aerospace Research east of Saint Joseph’s Lake. He also served as a consultant to the U.S. government via the Federal Aviation Administration, the Army, Navy and NASA.

His 2004 book, Aeronautics to Aerospace at the University of Notre Dame, co-authored with longtime Notre Dame colleague Thomas Mueller, made it to outer space. Astronaut Kevin Ford ’82 carried a copy with him when he piloted a mission of the space shuttle Discovery in 2009.

In his spare time, Nelson enjoyed handball, racquetball, golf and coaching youth soccer. He is survived by his wife, Julie, and two sons.

Alain Toumayan was a specialist in 19th- and 20th-century French literature, an author of two books and numerous articles whose interests in poets such as Charles Baudelaire and theorists like Emmanuel Levinas led him to the helm of Notre Dame’s program in philosophy and literature. But the quiet, gracious scholar was best known for his teaching and mentoring and for seeding his passion for French culture in others, both on campus and during his directorship of the study-abroad program in Angers, France.

Toumayan, a professor emeritus of French and Francophone studies, died October 4 at age 69.

He grew up in Bethesda, Maryland, and studied at the University of Pennsylvania and at Yale, beginning his teaching career at Johns Hopkins and Princeton before joining the Notre Dame faculty in 1989 and teaching here for the next 34 years.

Toumayan had a reserved nature. “He was so gentle, but so incisive. He was one of those professors who helped students write better, think better and read better,” said Rev. Greg Haake, CSC, ’99, ’06M.Div., an associate professor of French and Francophone studies who met Toumayan when he enrolled in the professor’s senior seminar as an undergraduate.

A lover of the outdoors, Toumayan enjoyed visits to Lake Michigan and kayaking on the St. Joseph River. Back on campus, his humility and kindness translated into a welcoming presence. He was often around his office, Haake said, available whenever a colleague or student knocked on his door — the first to ask students how their classes were going, always cultivating their tastes for the French language, literature and culture he so loved.

That love included music. An accomplished guitarist in bluegrass songs and classical compositions, Toumayan also taught one-credit classes on French liturgical music, directing and accompanying the student choir for monthly French Masses on campus.

He is survived by his wife, Vicki, and their two sons.

A man of many interests, John J. Uhran Jr. built autonomously moving robots and studied artificial intelligence long before most people imagined such things were possible — but he also loved to farm.

A native of New York City, Uhran studied electrical engineering at Manhattan College and Purdue University before joining the faculty of Notre Dame’s College of Engineering in 1966 and teaching here for 42 years. The senior associate dean emeritus and professor emeritus of electrical engineering and computer science and engineering died October 2 at age 87.

Uhran had an outgoing personality and a deep commitment to his students, said longtime colleague Gene Henry ’54, ’55M.S., a professor emeritus of computer science with whom Uhran, in 1990, helped establish the college’s Department of Computer Science and Engineering.

“We worked together on analog, digital and hybrid computers,” said Henry, who recalled collaborative research grants to equip student laboratories with the new technology. Uhran, he said, was a pleasure to work with, an excellent researcher, teacher, administrator and friend.

Uhran’s scholarship focused on communication theory and systems, signal processing and simulation techniques, as well as artificial intelligence and robotics. Determined to improve engineering instruction, he founded a series of conferences called First Year Engineering Education, in which academics and professionals shared best practices to enhance teaching methods — and Uhran’s own practices garnered him multiple awards. His service in the dean’s office lasted from 1991 until his retirement in 2008.

The devout Catholic was a cutting-edge technologist. In the early days of the computer science department, Uhran built robots and co-developed NDTran, a software package used to simulate large systems. Outside the academy, he served as a consultant for Bell Labs, Bendix Aerospace and Missile Division, and other firms.

An apartment dweller in boyhood, he always yearned for open spaces. Eventually the Uhrans bought a farm, where the professor planted fruit trees, tended a vegetable garden and kept bees — for 45 years his hobby and retreat. Uhran taught his children to drive the tractor and handle chores. Other interests included postage stamps, genealogy and collecting children’s books of the early 20th century.

He is survived by his wife of 57 years, Sue, three children and eight grandchildren.