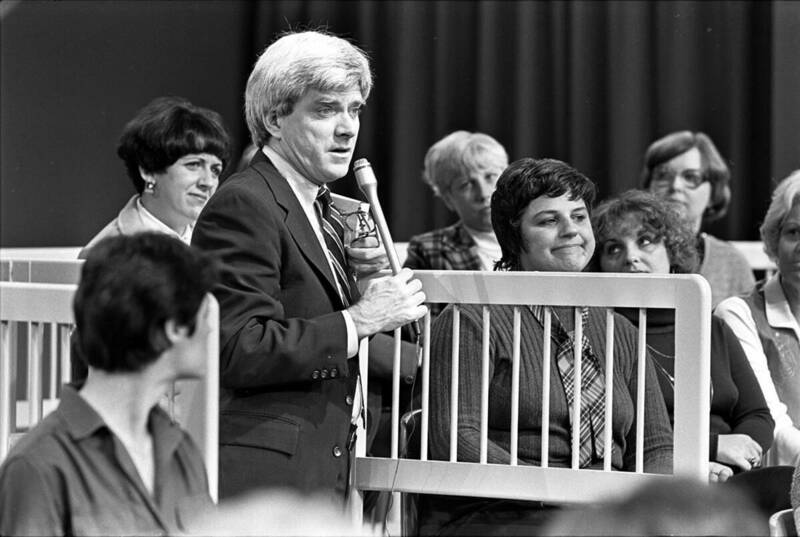

Donahue in 1980 with the audience he invited into the talk-show format.

Donahue in 1980 with the audience he invited into the talk-show format.

Editor’s Note: Phil Donahue ’57, who died August 18, 2004, at age 88, once dominated daytime television, his eponymous syndicated show a precursor — and, later, a ratings victim — to Oprah Winfrey. Known for bringing audience participation into the talk-show format, he became such a familiar cultural figure that one name sufficed — Donahue. Three different Saturday Night Live cast members did Donahue impressions over the years. Our latest Magazine Classic from 1997 explores his broadcasting career, and the evolution of his views on religion and politics as he put down the microphone after three decades on the air.

He won 20 Emmy Awards and made more than $100 million during a spectacular, 29-year career in which he hosted nearly 7,000 television shows.

As the inventor of a new kind of “talk TV” — an interview format in which audience members became a key part of the show — he created a permanent niche for himself in the history of American popular culture.

Donahue.

He’s 61 years old, officially “retired” from daytime television . . . after all those years of running up and down the aisles, microphone at the ready, barking endless questions at his adoring studio audience.

They canceled his syndicated show in January 1996, and he taped the final installment in May. Then he poured champagne for his production crew and blinked back the tears. He went out with class, a class act from beginning to end, even though he staged some silly shows for the sake of better ratings.

Now he says he’s finished, with no plans to return to television: “I mean this; I’m not being cute. I really don’t know what I’m going to be doing next.”

Phil Donahue ʼ57 had to endure the pain of watching his enormous popularity decline. “I wanted to go out winning 20 games. And we weren’t able to do that. . . . We woke up one morning and discovered that we were being beaten by this enormously popular and compelling person with the unlikely first name of Oprah.”

Did it hurt to watch Oprah zoom past him? You bet it did.

Donahue fought furiously to keep his grip on the daytime TV ratings. He put on a dress and sashayed across the stage in a desperate bid to attract viewers with a show on cross-dressers. He interviewed male strippers who set fire to their jockstraps, and gay men who exchanged wedding vows on camera, and braggadocio adulterers who gloated about cheating on their wives.

But those were aberrations. Most of the time, this Latin-spouting, former altar boy from Cleveland was determined to use his TV forum to explore “the vital issues that affect democracy.”

Donahue will tell you that his proudest accomplishment was his decision — starting way back in 1967, in Dayton, Ohio — to put ordinary citizens on camera, where they could quiz public figures and furiously debate the issues of the day.

“This was the radical idea known as ‘democracy,’ where we actually gave the people who owned the airwaves in the first place an opportunity to use them,” says the talk show host proudly. “During the early years, the thinking among television management was that you didn’t want to just let ordinary people stand up and speak. You see, they’re not very informed, and they’re overweight, and they’ll drag your show down.

“And there was a lot of sexism involved, too. After all, what does a housewife know? I mean, that kind of attitude was palpable in 1967, when we signed on [at a Dayton TV station].

“Back then, a housewife was a person who cared only about covered dishes and needlepoint and colic. But we challenged that idea. We put the housewives on camera, and lo and behold, lo and behold ….”

The rest is TV history.

From the beginning, Donahue understood one fact: In the brutally cutthroat world of syndicated television — where you must sell your show to each individual station that airs it, year after year, as opposed to letting ABC or NBC or CBS do it for you — the battle for “audience share” never stops.

Slip once on the ladder in syndicated TV, and they will take your name off the marquee before the next sunrise.

That was the war Donahue fought. After all his years of astounding success, including an entire decade (1975-85) in which he reigned as the unchallenged superstar of daytime television, he eventually began to lose the ratings battle.

The tide was turning against him; after 1985, a new generation of TV watchers was emerging. The housewives who had once worshiped him were all at work now, as the single-income family all but vanished from the American scene.

At the same time, America was “dumbing down.” Almost overnight, the audience for TV shows on “auto safety” or “prison reform” or “waste in government” vanished.

For Donahue, the long decline probably began in 1986 — the year the hugely charismatic Oprah Winfrey first passed him in the ratings and never looked back. Then, all too swiftly, the mob of Donahue imitators began to arrive.

By the 1990s, the “Generation X” viewers were watching younger, savvier TV talkers — Ricki Lake, Jenny Jones, Montel Williams — who weren’t afraid to give their audiences the sensational, soap-opera-style entertainment Donahue had always spurned.

Now there were 14 syndicated daytime talk shows competing for viewers each day. And suddenly, Donahue was tied for eighth place among his hard-scrapping competitors.

In 1995 came the Kiss of TV Death: WNBC, the New York City flagship for Donahue’s syndicate, Multimedia Entertainment, announced plans to cancel his show.

It was over. When you lose New York, you’re done. By May 1996, he was pouring the farewell champagne for his staffers, after joking with a Washington Post reporter: “It’s not easy to talk about your death, ya know?”

What was it like to be Phil Donahue, to watch your magic evaporate as the TV culture that spawned you deteriorated relentlessly to what the critics dubbed “tabloid trash”?

The question brings a strange transformation before your very eyes — as this thoughtful, 61-year-old “retiree,” suddenly metamorphoses into Donahue, the image everybody knows from all those years on television.

Here’s what happens: It’s a mild afternoon, and we’re sitting in the gorgeous living room of the Donahue penthouse, home of Phil and his wife, actress marlo Thomas, which overlooks the blazing autumn foliage of nearby Central Park.

We’re a long way from Cleveland and Our Lady of Angels parish, where Phil grew up saying the rosary every night during Lent and serving Mass in a scarlet-and-white cassock every morning. But here we are. Now Phil Donahue is trying to explain how his show changed — how America changed — and you can watch him becoming Donahue, right here at the table.

First the vivid blue eyes flare. Then the arms come up, those leaping scarecrow-flappers — remember? — and his voice is booming, and you begin to hear that rising, Irish inflection, so that every sentence becomes a question — remember? — and it’s the kind of melodramatic, almost wailing inflection that tells you you’re in the Irish-Catholic part of town.

Donahue: “And then Oprah Winfrey began to lose weight? And millions of Americans watched her as she lost it? And then we had millions more tune in, curious to know if she was gaining it back? And I really don’t think she wanted to be the television personality who went on a diet, and she isn’t that. She’s a thousand times more than that!

“But it became probably the single most effective promotional event in the history of daytime television. Every magazine cover, every story . . .”

Now Donahue trails off, fades back to Donahue, and he speaks quietly: “And here was Phil, on the other station, with his hair getting grayer. And not able to get the Reagan administration to call us back in the 1980s . . . and perceived as a big-spending liberal who criticizes America — rather than being proud of the country that allowed him to be so wealthy.

“A man who had received an education because of the lifelong sacrifices of men and women religious and then had the gall to criticize the church! A person who was pro-choice, pro-gay rights, pro-affirmative action . . .

“A person who criticized often Reagan’s presiding over the greatest concentration of wealth in the history of money. And who criticized the bombing of Tripoli and the invasion of Grenada.

“And, meanwhile, much of the audience that had grabbed us with both hands in those early days — that audience was largely gone by the mid-1980. . . . And incredibly, the other talk show hosts were doing things that spoke to the Generation X people, and in a most unusual way.”

A pause. A sip of tea. Then once again he’s transforming into the image, the image we remember so well.

Donahue: “A guy sits there with his girlfriend, and her best friend, and he says, ‘Honey, I went to bed with her last night. And I want to apologize. Will you marry me?’”

The arms come up: scarecrow-flappers!

“And the audience goes: ‘WHOOOOOOOOHHHHH!’”

Then quieting again, returning to himself. “Look, I’m not criticizing this. It’s just that the genre today remains focused on ideas that somewhat resemble the old Dating Game. . . .

“There’s a good deal of manipulation now, which troubles me a bit. We didn’t do that. There’s also a lot of planning of questions in the audience. And you’re losing some of the authenticity of the democracy, without which we never would have lasted 29 years.

“Because it’s the audience that got us here. I’ve said it often and I truly believe it. I assure you: I’m not charismatic enough to carry a show all by myself with [Congressman] Dick Gephardt! You know, it’s the audience standing up to say how they really feel. It’s the interchange. . . . That was our innovation, and that was the legacy we leave behind.”

“There’s no question that he invented a billion-dollar format,” says New York TImes TV critic Bill Carter ʼ71. “Phil Donahue got there first, and that format — audience participation, built around a controversial topic — has made him a hundred million dollars, and it’s made Oprah Winfrey several hundred million dollars by now.”

According to Carter, also the author of a best-selling book about TV talk-shows, The Late Shift, Donahue simply stayed too long, after it became obvious his era was over.

Although the show featured a lot of bizarre topics, Carter points out that they were scheduled for use mostly during “Sweep Month,” when the vitally important ratings are decided. Deep down, says Carter, Donahue wanted to be Ted Koppel — and to be thought of as a serious news journalist.

“Did you know that at one point, he was thought of as the next possible host of the Today show? … But later, when the competition came, Donahue had to make a choice. He could go out of the business, on the high note that he had achieved, or he could try to compete with them. And he chose to stay on and compete.”

Why did Donahue stick around for so long? “He’d already made $100 million,” says Carter. “This wasn’t a guy who needed to stay in the business for any other reason but that he liked to be in the public eye, and to have a forum and to be a celebrity.”

Carter also suggests Donahue might have stuck it out because of his “messianic sense” that he had a moral message to bring to America: “There’s something about Donahue, something you can’t put your finger on — he’s so morally righteous!”

“He was quite thoughtful and sincere,” says J. William Graves ʼ57, a Donahue classmate who today serves as a Kentucky Supreme Court justice. “Believe it or not, he was always thinking about philosophical problems and trying to figure out the Holy Trinity. He was probably the most devout member of our group at that time.”

Adds John Carlin ʼ58, who later would spend eight years in the priesthood before receiving permission to leave and enter the laity. “There’s no question that Phil took his religion seriously. As a matter of fact, I’ve always thought it was kind of sad — that all Phil saw was the ‘old’ church.”

That heavy dose of the older, more rigid church, Carlin believes, deeply affected Donahue’s outlook in later years.

If you want to see Donahue turn into Donahue, ask him his opinion about some of the recent struggles in American Catholicism: “They keep asking me,” roars Donahue, “how dare I criticize the church? I, who as the beneficiary of a Catholic education which was the result of the lifelong sacrifices of the brilliantly talented men and women who taught me — HOW DARE YOU CRITICIZE THE CHURCH?

“But you know, I cannot be so humble as to shut up! Not when I see the un-Christian treatment of women by the male-dominated church. Not when I read about the legitimization of homophobia by the same church!”

He pauses and then softly, softly: “As you know, I’m a divorced and remarried Catholic. And I don’t go to communion. I’m like the divorced aunt of my childhood, over whom all of us crawled to get to the communion rail. She couldn’t go to communion — divorced! And I will never forget those long moments of discomfort. . . .

“But I believe that an annulment is a cruel and empty exercise. How dare they ask me to tell my five children that my marriage to their mother never existed — and then demand a fee? The temerity — a fee!

“It’s four or five men behind a closed door, and they’re going to decide whether or not my marriage ever existed? I think that’s a cruelty. An absurdity. You don’t do this to people!”

Phil’s father — a lifelong furniture salesman at Bing’s, in downtown Cleveland — was deeply affected by the Great Depression. Like millions of other Americans, the Donahue family took a terrible financial pounding during the early 1930s. (“My father had been a musician,” Phil will tell you, “but he’d sold his bass fiddle for soup during the Depression. And then the year I was born, 1935, he finally got his job at the furniture store.”)

As a kid on Cleveland’s west side, Donahue was brought up to believe that two institutions were above reproach: the country and the Catholic church. In Our Lady of the Angels parish, he learned about serving the Latin Mass on snowy winter mornings.

There are millions of older Roman Catholic men in America today who remember it the way Phil does. They remember the great privilege that was theirs — inside that charmed circle illuminated by the light-blazing altar. They remember the awesome responsibility of pouring the blood-red wine over the priest’s fingers.

“I used to serve Benediction on Wednesday nights,” says Donahue with a nostalgic smile. “This was at the Poor Clares convent for cloistered nuns, and we’d be going through the benediction service . . . and from behind the wall would come the voices of these women who never saw the outside.”

Now a strange thing happens, here in the Fifth Avenue penthouse: Donahue throws his head back, and suddenly he’s chanting the ancient Latin: “In nomine … nomine patris … Alleluia!”

And then he’s singing: “Tantum ergo, sacramentum. . . .

“And I’m tellin’ ya, the priest was ancient. He’d move slowly up the steps, carrying the constrance before him, and then he’d place it on the altar. And then he’d unbutton the clasp on his shawl . . . and he’d let it fall from his shoulders —

“And I’d lunge for it! Trying to catch it before it hit the ground! Can you imagine? Can you imagine how powerful you felt that, as an altar boy?”

This was the vision 18-year-old Phil Donahue brought to Notre Dame in the autumn of 1953. Having graduated from Saint Edward’s, a high school launched by the Brothers of Holy Cross in Cleveland in the late 1940s, Donahue figured he’d have a “pretty good shot” at getting into “another CSC institution” like Notre Dame.

“Let’s understand this,” he says today, “Phil Donahue is a very lucky fella, and I mean with a capital L. Why, I never even took an SAT exam to get into Notre Dame. There were at least a dozen of us from Saint Edward’s who wound up in South Bend, and I really think it was a courtesy extended by Notre Dame to this fledgling CSC institution in Lakewood, Ohio.”

Regardless, he was in. And now his Catholic education began in earnest. “Let me tell you — I got through that first year on fear alone,” he says with a laugh. “I majored in business administration, and I barely survived. Nobody ever mistook me for a genius.”

He clearly remembers the joy of learning, however. “The most exciting teacher I had was Father [James] Smyth, in theology. It was 1955, and we read books on the Index [the Vatican’s list of forbidden books]. Authors like Descartes: ‘I think, therefore I am!’ You can be sure that idea wasn’t well received by the Vatican!

“Or Immanuel Kant. The ‘Prolegomena To Any Future Metaphysic.’ You know, I’d be talking to a girl from Saint Mary’s, and I’d drop that one into the conversation. I mean, I was a terrible showoff, and I loved it. But he had us reading the Summa of Thomas Aquinas, the Five Proofs for the existence of God.”

Although thrilling, Notre Dame also was terrifying, because he barely survived: “We were in Zahm Hall, and we had the most talked-about rector on campus: Father [Paul] Fryberger. He was known as the ‘Sneakin’ Deacon’ — and to this day, there are former Notre Dame students who will tell you that he wore only one shoe at night — so that when he ran down the hallway, it would sound like he was walking!

“The misdemeanors, the chicanery. And finally the bill of particulars became long enough, at the end of my freshman year, that I was obliged to go see Father [Charles] McCarragher — the notorious ‘Black Mac.’”

Donahue knew what the meeting might mean. “My father was probably making $7,000 a year in that furniture store. And he was terribly proud of the fact that I was at Notre Dame. to have had to go home and tell him, tell my mother that I’d been thrown out — that would have been Dante’s Inferno.”

When the worried boy was ushered into the prefect of discipline’s office, Black Mac roared at him: “What accounts for this behavior?” Most of that behavior involved relatively minor infractions, like talking after 10 p.m. “Well,” Donahue managed to answer, “I think it’s immaturity, Father.”

“And he stared at me for what seemed like an eternity. And then he said, ‘You’ll come back here in two weeks, and we’ll decide whether or not you’ll remain at this university.’

“When I walked out of that building, my tongue was sticking to the roof of my mouth. But I survived. No hatchet!”

A struggle — and he isn’t exaggerating. If you talk to the dozen-odd ND alumni who make up “The Gang” — a group of 1957 graduates who still get together each year for Notre Dame football games and fishing trips — they’ll all tell you pretty much the same thing: Notre Dame in the mid-1950s was a very, very serious place.

“Phil struggled to survive, and so did I,” says George O’Donnell, a “gang member” who first met Donahue in the third grade at Our Lady of Angels parochial school in Cleveland. “I had to have my parents come to campus and meet with the brass in order to be admitted for my sophomore year.”

During their undergrad days, says O’Donnell, Donahue seemed to accept the church’s teachings without a quibble. “I don’t think he questioned them at all. I think that came much later — after he began to see some of the problems in the church.”

Donahue agrees: “At Notre Dame, I was a pretty devout Catholic. Every night after dinner, we’d climb into our parkas and head out to the Grotto for prayer. We’d stand out there in the freezing cold for half an hour at a time, just praying and meditating.”

By the beginning of his junior year, Donahue had found a favorite hangout — Washington Hall, the headquarters for University Theater. “I was over there rehearsing every night. And that was some of my first exposure to appearing before an audience and realizing that you could make people laugh.”

His big break came when WNDU-TV hired him for a dollar an hour. “At first they had me plugging in microphones for the audio, or running the control room. And then suddenly one morning at 5:30, I’m standing in front of Farley [Hall], and I’m on the air. I’m doing the pigs — the Farm Report. And nobody’s watching. Half the crew was asleep. I’m standing outside, reading hog prices from Indianapolis — live on TV!

“Then I’m up in the booth: ‘This is Channel 46, South Bend!’ And pretty soon, I’ve also got a job as a disc jockey at WNDU Radio. So there I am . . . I’m in the plays. I’m doin’ WNDU. I’m fallin’ in and out of love! I’m surviving as a student.

“Really, I can’t imagine a richer, more varied academic experience than the one I had at Notre Dame!”

All too soon, it was time to leave.

Donahue soon began working as a radio announcer in Dayton, Ohio. He married a solid, down-to-earth Irish girl; they had “five kids within six years — until we finally gave ourselves permission to start using birth control.”

It was here, while “busing” his kids from a “nice suburban neighborhood” into Dayton’s inner city and while becoming increasingly caught up in the civil rights movement and the women’s movement and the anti-Vietnam War movement, that the former altar boy began to have his first grave doubts about the Catholic Church.

“We were in the middle of building a brand-new, $80,000 Church of the Incarnation in the suburbs,” Donahue says, “and I had begun doing a lot of shows on racism. And you didn’t have to be a genius to see that the Catholic Church was raising another generation of racists in our neighborhood.

“All the teachers in the parochial schools were white; all the saints were white; the guardian angel who helped me over rickety bridges was white. God the Father was white, and the Holy Spirit was a white dove! Devil’s food cake is black, and angel’s food cake is white . . . but when we went to the bishop in Cincinnati about spending all these resources on a new church, he told us: “The poor you will always have with you.’”

Donahue started moving away from the church, no longer going to Mass every Sunday. “I guess it was another moment of realizing that there is no Santa Claus,” he says. “[M]y church was made up of finite, imperfect human beings, and I began to see the terrible sexism of the church, the way that it utilized the talents of women religious for its school system.

“Do you know that in the fifth grade I could serve Mass, and the nun who taught me was not allowed on the altar during the celebration? A church that was telling Catholic women to go back to the husband who was beating them….

“And while I was doing all those shows, I came to realize that ‘gayness’ is not a moral issue. It’s not a choice. You don’t wake up one morning at age 13 and say, ‘I think I’m gonna be gay!’ And if it isn’t a choice, how dare my church condemn me?

“To see the church hang onto this anachronistic, medieval, bigoted ideology — born, as all prejudice is, out of fear and ignorance — that’s a source of real concern to me.”

So there he is: Phil Donahue.

He spent all those years asking people questions on television. Now he’s asking them of the institutions that raised him, the institutions in which he once believed.

He thinks he has a right to the questions — in spite of the enormous success he’s enjoyed in America and the huge wealth he’s piled up. “When I’ve criticized Reagan in the past, people like Rush Limbaugh have said to me on the air: ‘How much money have you made during this period?’

“In other words, if you make money, you gotta shut up. And if you’re the beneficiary of a Catholic education which is the result of the lifelong sacrifices of brilliantly talented men and women who taught you, dare you criticize the church?

“But you know, I cannot be so humble as to shut up!”

Tom Nugent is a Baltimore-based freelance writer and author of Death at Buffalo Creek, published by W.W. Norton.