The “poor boy” gasped when he saw “the most wonderful locks and keys” his “youthful eye ever rested upon.” The sight inside Brother Benoit’s locksmith shop was a marvel to orphan Joseph Lyons, 14 years old and newly admitted to the Manual Labor School. The rookie apprentice would remember it for the rest of his life.

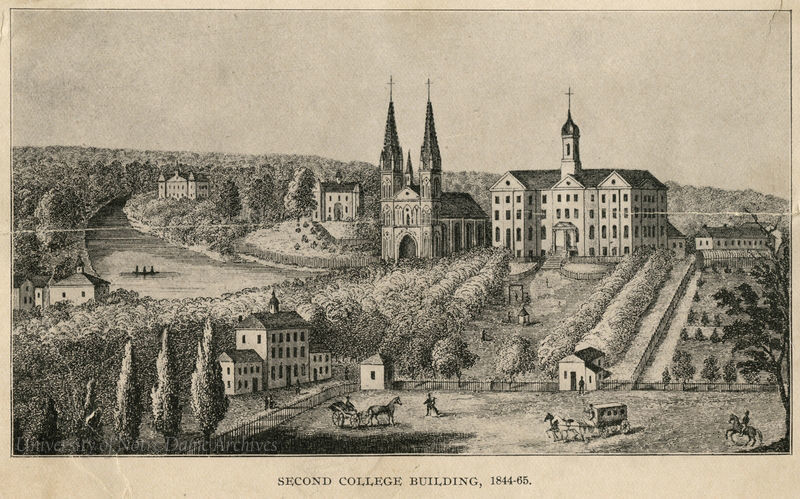

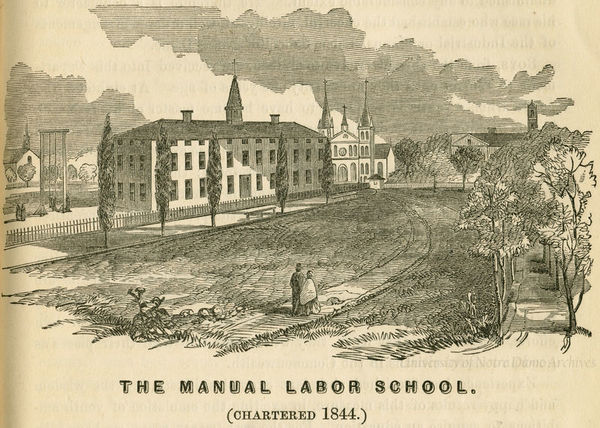

Founded in 1844 under the same legislative charter that created the University of Notre Dame, the Manual Labor School was a constant concern of Father Edward Sorin, CSC, a direct response to the needs of the United States’ then-growing population of orphans, runaways and “poor boys,” as they were unapologetically described in broadsides and the University’s annual catalog. The situation was particularly dire in northern Indiana, a less prosperous part of the state than the rolling farmlands closer to the Ohio River.

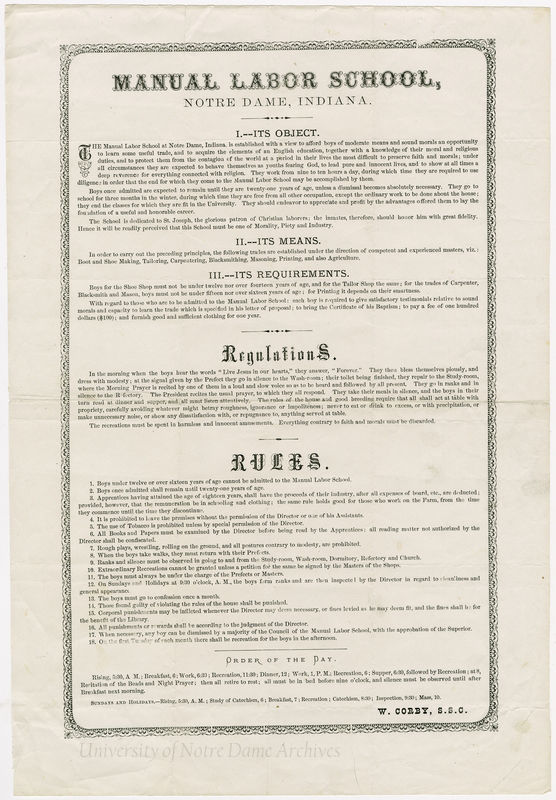

At the outset, and for most of the years that followed until the school’s closure in 1919, the typical Manual Labor School apprentice was between the ages of 12 and 18 and would stay three or four years until he had mastered a trade or two. But his interactions with tuition-paying Notre Dame students were minimal, and the scant evidence remaining of the school’s 75-year existence in the shadow of an emerging university tells a story of second-class citizenship on campus. Not a single available photograph captures these boys, their daily lives or the work they did inside the shops.For many years, Sorin’s effort remained the only one of its kind in the U.S. No mere orphanage or reform school, it was a place where adolescents could learn a trade and receive a basic education before venturing back out into the world as men. Carpentry, boot- and shoemaking, tailoring, farming, locksmithing and metal work were the options available when Lyons arrived in the late 1840s; at times the offerings would expand to include skills such as printing, brickmaking, baking and masonry.

Lyons came from a family of 13 children in rural Michigan. His parents had died, so he had much in common with his fellow apprentices, who numbered as many as 60 in any given year. Until the railroad came to South Bend in 1851, most of the boys came from northern Indiana, and many were Irish. From Notre Dame’s earliest days, missionary priests tried to serve the local Catholic population of poor farmers, many of whom felt that a home education was sufficient — and therefore weren’t clamoring for schools.

Homeless, uneducated and unskilled teenage boys had caused concern for years. The circuit-riding Father Stephen Badin was among those who urged civic leaders to do something, and he held out similar hopes to Sorin when he donated the land that would become Notre Dame. So from 1844 on, the young Holy Cross priest held responsibility for two schools with distinct missions: a “university” that would deliver higher education to the sons of frontier farmers and merchants, and a vocational training program for a barefoot class of children who could barely read or write.

Once rails connected Notre Dame to the rest of the country, the school’s reputation spread fast and far. By the time of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which promoted the Manual Labor School in a popular exhibit, the Catholic bishops in Cincinnati and New York had begged Father Sorin to send them Holy Cross brothers who might open similar schools in their dioceses. Sorin always replied that he could not spare a single brother.

Life in 19th century America was nearly as segregated by class as it was by race, and life at Notre Dame was no different. On campus, the lane that would become Notre Dame Avenue over time marked the division. Strong, brick edifices such as Washington and St. Edward’s halls would rise on one side, while the congregation’s barns and the makeshift wooden buildings where the apprentices worked, studied and slept occupied the other. After a fire destroyed the carpentry and blacksmithing shops in 1849, the structures that replaced them were erected farther to the west and away from the Main Building, near the present-day locations of Walsh and Badin halls.Instead, when possible, bishops out east, from Detroit and Cincinnati and Wheeling, West Virginia, sent their orphans to Notre Dame. One story from 1858 stands for many: Sisters of Mercy in Chicago escorting four boys to campus from their orphanage because the lads had turned 12 and were no longer eligible for the nuns’ care.

The crowded dormitories proved cold in winter and blistering hot in summer. Bedbugs were a problem. Dust and insects filtered in through seams in the walls, along with the smells and noises of the farm. The prim landscaping around the church and the Main Building stopped well short of these dwellings and workshops.

Of course, it all constituted an improvement for most apprentices, who, if they or their patrons could find a way to pay or skirt the one-time admission fee — $40 at first, $200 or more by the turn of the century — must have considered themselves fortunate. They’d wake up early enough to eat a cold breakfast with the brothers at 6 a.m., then spent eight or nine hours a day learning how to construct things by hand and a few more in the evening on reading, writing, math and other basic courses. (An 1845 advertisement also mentioned instruction in bookkeeping, music, French and “Purity of Language.”) Joseph Lyons, more ambitious than most, taught himself Latin in those dimming hours before bedtime.

Regarding their religious formation, one priest observed that the apprentices “frequent [the] sacraments without compulsion.” The brothers encouraged baptism for all those who hadn’t already received it, by all accounts giving the boys a stronger religious push than their peers at the University were getting.

Schooling in the 19th century could be a gritty endeavor. In his 1881 gradebook, Brother Francis de Sales recorded the following impressions of his pupils: Fitzpatrick, “lazy and bad”; Kennedy, “no talent and lazy.” McHenry and McCarthy, “not good.” Sullivan, “bad.” Flanagan was a “wild boy.” Arthur: “Paid no entrance fee. Lazy.” McGill: “Has fits frequently.” Just six of the brother’s 26 students, whom he saw for evening classes after a routine supper of cold potatoes or something similar, rated a “good.” Nothing higher.

Harder for these young men to accept, as the years went by and the University began its academic ascent, was the social bias of the well-dressed boys across the way. “No intercourse with the students” was how one evaluation phrased it, even though some Notre Dame boys wore suits made by hand in the tailor’s shop. The apprentices, by contrast, typically had no suit for Sundays other than a loose “roundabout” jacket — coarse, unadorned and simply made — and wore rough, dark clothing for work. One description noted that apprentices would need two sets of clothes to last them through the year.

Still, the trade school boys were fortunate to be educated by talented Holy Cross brothers, several of whom had perfected their own skills in Europe. Whether stern or kindly, the brothers not only furnished the boys with shoes and taught apprentices like Lyons how to make prizewinning footwear, but they were also known to share their handmade bootblack. Brother Gus would travel to Chicago to ask tailors for discarded swaths of fabric so his boys could work with good materials. And when apprentices sold their own creations, the brothers would save the money and give it back to them as they prepared to depart.University students would not even accept the apprentices as waiters in the Main Building’s formal dining room. Young men who worked with their hands were considered too uncouth for fine dining — they sometimes reported for work after hours of farm labor — so that arrangement eventually failed. Neither did the groups interact socially. While The Notre Dame Scholastic reported the rare baseball game between the two student bodies, the apprentices’ team, the Atlantics, mostly played sides from nearby towns on a field near the spot the Hammes Bookstore occupies today.

Beyond that, the boys developed an affinity with the brothers, whom they likely perceived as second-class citizens among the adults. “Brothers are not wanted around the college as teachers, as is very clearly seen by everyone,” one brother wrote in 1877. Albert Zahm, a professor of mathematics and mechanics, and younger brother of the more famous Father John Zahm, CSC — who lectured to the Minims but not to the apprentices — once described the Manual Labor School as located “in the neighborhood of Notre Dame.” In 1891, Zahm wrote in the Scholastic about the apprentices who had repaired plumbing and built machinery for his lab, including dynamos, lathes valued at $600, reamers and twist drills. He praised their mathematical knowledge of patterns and summed them up as “poor boys” training to be “men of morals and manners.” He stopped short of saying how well they might do in his class.

Some on the University faculty criticized Sorin for giving too much attention to the homeless boys from the countryside, but the trade school had its distinguished advocates, too. The most prominent was Bishop John J. Keane, the founding rector of the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. In a note thanking Brother Gus for his tour of the school during a visit to campus, Keane wrote that Sorin “may have many claims to be considered a great man but posterity will recognize that the one most striking of all is having so justly appreciated the importance of the Department of Industry. . . . What would the world be without the workshop of Nazareth; and what would Notre Dame be without the workshop of Brother Gus?”

By the turn of the 20th century the brothers were struggling to keep the numbers they needed to staff the school. The boys’ products were getting harder to sell as cheaper, mass-produced goods became more widely available.

The school’s closure in 1919 coincided with the ascendancy of one of its most distinguished alumni to the helm of the University. Notre Dame’s ninth president, Father James A. Burns, CSC, had learned typesetting before transferring into the Main Building, studying chemistry and following his religious vocation. Whatever gratitude and nostalgia he may have felt toward the school was superseded by his vision of raising money for the creation of a modern research university.

By that time, Joseph Lyons, a revered professor of Latin and elocution, had long since died, his name soon to be memorialized in one of the campus’ most picturesque residence halls. Decades earlier, Sorin had recognized the abilities of both young men, seen them as potential clergy and offered them scholarships. Lyons and Burns remain the Manual Labor School’s most notable graduates.

Today the spirit of social engagement that created the school has taken different forms, and student attitudes have changed, but the trade school that set an example for decades has mostly been forgotten. Researchers have written a few articles, but most University histories either ignore it or brush past it in one or two pages.

In 2019, I made a pilgrimage to the site of the old workshops near Badin Hall to honor the brothers and their charges. I knew I would not find one of those official historical markers often erected for far less significant accomplishments. I felt I might at least mark the century since the closing of the Manual Labor School by standing in the “neighborhood” known by so few. How many lost boys arrived here barefoot but walked out with bootblacked shoes and the skills they needed to make a life for themselves? They belong to Notre Dame as much as anybody.

Marion T. Casey lives in South Bend and is collegiate professor of history at the University of Maryland’s University College, teaching online students studying abroad. Contact her with Manual Labor School stories at caseyemery@aol.com.