The last time Knute Rockne ever coached a Notre Dame football team was also the last time the Four Horsemen ever suited up for the Fighting Irish.

The five men came together for a December 14, 1930, exhibition game at New York City’s famed Polo Grounds. Six years earlier, that spacious haunt on the western shore of the Harlem River had been the site of the Horsemen’s legendary 13-7 victory over Army.

It was that 1924 game that prompted sportswriter Grantland Rice to pen his famous lead: “Outlined against a blue, gray October sky the Four Horsemen rode again.

“In dramatic lore they are known as famine, pestilence, destruction and death. These are only aliases. Their real names are: Stuhldreher, Miller, Crowley and Layden. They formed the crest of the South Bend cyclone before which another fighting Army team was swept over the precipice at the Polo Grounds this afternoon as 55,000 spectators peered down upon the bewildering panorama spread out upon the green plain below.”

Quarterback Harry Stuhldreher, halfbacks Jim Crowley and Don Miller and fullback Elmer Layden, all seniors that fateful fall, were forever after known as the Four Horsemen.

For the 1930 game, a team of 24 Notre Dame alumni took the field against the New York Giants of the National Football League. The Giants were regular tenants at the Polo Grounds, which was operated by Charles Stoneham, owner of baseball’s New York Giants franchise.

Stoneham gave the stadium rent-free that afternoon to the two teams. The exhibition game, staged in the early days of the Great Depression, was a fundraiser for Mayor Jimmy Walker’s unemployment relief fund.

While the Notre Dame alumni regarded the game as a way to lend a hand to those in need, the Giants treated it like a referendum on their own existence. What made the do-or-die attitude that Giants owner Tim Mara and player-coaches Steve Owen and Benny Friedman took toward the game so remarkable was that the Giants were among the NFL’s most successful and popular franchises.

The New York team had just finished its season in second place in the 11-team NFL and drew the second-best gate receipts of any team in the league. Nevertheless, the contest against the Irish graduates overshadowed the other dates on their calendar.

More than 50,000 fans gathered that Sunday in upper Manhattan to watch the “Notre Dame All-Stars.” Not the hometown Giants. According to contemporary accounts, the crowd greeted Rockne’s team with raucous applause while the Giants came out of the cavernous stadium’s first base dugouts to little notice.

The Giants were not used to this kind of tepid reaction at the Polo Grounds, but then they weren’t accustomed to seeing so many people show up for one of their games, either. In eight home contests that season, New York had drawn a total of 82,000 fans to the ballpark — an excellent attendance figure in a still-fledgling NFL that included clubs in Providence, Rhode Island and Portsmouth, Ohio, but small potatoes compared to the box-office appeal of major college football teams.

North and south, east and west, the collegiate game in 1930 drew much larger crowds than did pro teams, which in the 1920s had proven more likely to fold at season’s end than to turn a profit. Notre Dame had been playing regularly in the New York metropolitan area since the 1910s, often drawing better than 50,000 fans to the Polo Grounds or, more frequently, Yankee Stadium, to see the Irish take on Army.

The same weekend that the New York Giants finished their 13-4 campaign, Rockne’s Notre Dame team completed a perfect 10-0 season. A reported 88,000 spectators in Los Angeles’ Memorial Coliseum saw Notre Dame throttle a previously 8-1 Southern Cal team 27-0, securing the Irish a third consensus national championship under Rockne.

Notre Dame had spent the Saturday before the USC game outslugging Army in a 7-6 donnybrook before 110,000 spectators at Chicago’s Soldier Field. While Notre Dame’s 1930 team might not have the reputation of the ’24 club, Grantland Rice himself regarded the ’30 Irish team as the best in college football history.

With the exception of Southern Methodist and Army, Notre Dame wiped out every team on its schedule, outscoring opponents by an unprecedented 256 to 74 margin. By season’s end, the Irish boasted a 19-game winning streak that included the entirety of the team’s 1929 and ’30 championship seasons.

Tim Mara, a longtime fan of the Fighting Irish and booster of the team’s appearances in New York, had tried to convince Notre Dame officials to allow their actual 1930 team to play in the relief game.

Rockne would not agree to it, fearing it would overextend his team after a tough season to crisscross the continent by rail on consecutive weekends, playing in southern California on one Saturday and in Manhattan the next.

Instead, Rockne persuaded Mara to accept a game against a temporary barnstorming team that consisted of past Notre Dame greats and a handful of current Irish players.

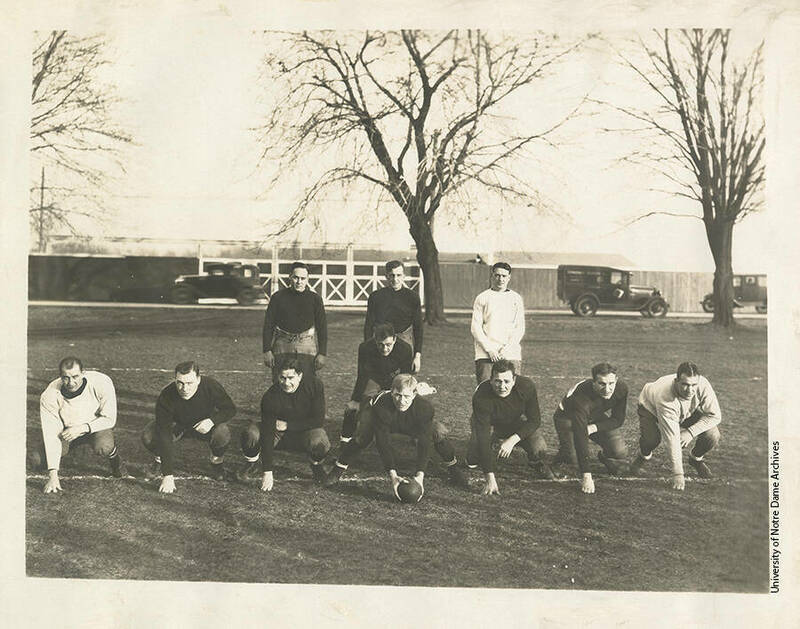

Rockne assembled a formidable team for the game. He convinced all of the Four Horsemen to participate. All four had long since ended their playing careers and joined Rockne in the college football coaching fraternity.

A majority of the “Seven Mules” who had opened holes for the Horsemen would also be in uniform. Jack Chevigny ’31, the halfback whose 1928 touchdown against Army helped the Irish “win one for the Gipper,” would play. And assistant coach Hunk Anderson ’22, who starred as a guard on Rockne’s earliest Notre Dame teams, agreed to suit up.

Further, Rockne convinced a handful of standouts from the unbeaten 1929 team to play, as well as the biggest stars on his current club — most notably two-time All-American quarterback Frank Carideo ’31.

All told, Rockne spent four days with his all-stars in South Bend before the team departed for New York. When his college team returned from the West Coast, the players joined in a parade held to honor the soon-to-be crowned national champions, so practice did not commence until Tuesday afternoon. Rockne soon realized that his side was heavy on backs, light in the trenches and not quite as fit as he would have imagined when he agreed to the game.

The Giants, on the other hand, had a massive and cohesive front line — much larger than Rockne’s cobbled-together collection of “mules” and much more accustomed to playing together. In quarterback Benny Friedman, the sport’s most exciting and explosive player since Red Grange, the Giants had arguably the first great passer in football history.

Moreover, the Giants prepared for the charity contest as if it were a land invasion, spending the week in full contact practice and allegedly using operatives to have an illicit look at what Rockne’s team had in store for them.

The Giants had a chip of sufficient size on their collective shoulders to befit their moniker. Mara had been boasting for years that professional football was superior to the much more popular and widely heralded college game, drawing guffaws from the sport’s cognoscenti.

For weeks in advance of the game, advertisements reading “SEE THE FOUR HORSEMEN RIDE AGAIN” splashed as headlines across every major newspaper in metropolitan New York. The New York Telegram’s Dan Daniel, one of the era’s best-known sportswriters, chaired the game committee and hyped the contest in print and broadcast media almost exclusively as a chance to see the Notre Dame legends in action.

From the opening kickoff, the home team dominated play, pinning the Irish back near their own goal line. To the crowd’s delight, Rockne started the Four Horsemen, who were soon swallowed up by the Giants’ defense.

The Giants took a 2-0 lead just over a minute into the contest when New York’s defensive front line threw Stuhldreher for a loss in the end zone. The safety proved a harbinger of the all-stars’ dismal offensive performance.

Notre Dame backs made no headway against a six-man Giants defensive line that manhandled their much smaller and slower adversaries in the trenches. “More than 50,000 cheered every futile thrust of Knute Rockne’s improvised squadron of former Notre Dame football players against the super line of Tim Mara’s team,” Marshall Hunt of the New York Daily News reported afterward. Notre Dame gained just 34 yards that afternoon and never moved the ball past midfield. Irish passers went 0 for 9 and served up a pair of interceptions.

New York’s offense proved just as effective as its defense. Friedman capped off an early second-quarter scoring drive with a four-yard touchdown run. As halftime approached, Friedman called his own number again and scampered through a hole in the Irish defensive front for a 22-yard score. New York held a commanding 15-0 halftime lead.

As the teams headed for the locker rooms, Rockne chided Giants team president Harry March for allowing the Giants to embarrass his squad in a purported charity game.

The Notre Dame coach asked March to call off the dogs in the second half, which the Giants largely did. New York played its reserves for the remainder of the game. Aside from a third-quarter touchdown pass from Hap Moran to Glenn Campbell, the Giants controlled the ball but showed little interest in adding to their margin.

The 22-0 final score headlined all newspapers in the city, earning the hometown team a grudging respect from writers who had previously discounted the professional game. Nevertheless, they were treated like sparring partners by many of the New York papers, who instead focused their coverage on the plucky performance of a Notre Dame alumni team that had assembled just a few days earlier.

Most reporters covered the game as if it were a star-studded charity gala, giving more column-inches to the dignitaries in attendance than to a blow-by-blow of the contest — and seeing the Notre Dame performance in the same light as Rockne did. The Irish were doing their part to help people in need.

The charity game raised more than $115,000 for Walker’s fund, worth close to $2 million in 2021 dollars. The smashing box-office success proved to be Knute Rockne and the Four Horsemen’s final victory together. Less than four months later, on March 31, 1931, Rockne died in a plane crash in Kansas.

Stuhldreher, Crowley, Miller and Layden never again donned the blue and gold or shared a backfield.

Clayton Trutor earned a doctorate in U.S. history from Boston College and teaches at Norwich University in Northfield, Vermont. He is the author of Loserville: How Professional Sports Remade Atlanta and Atlanta Remade Professional Sports (University of Nebraska Press). Find him on Twitter @ClaytonTrutor.