In the late 1960s, issues of race, war and gender roiled campuses across the nation. Police clashed with students. Students clashed with their administrations. Upheaval was in the air.

But at Notre Dame, an unexpected instigator triggered a violent duel between police and students: pornography.

It started innocently enough with an academic inquiry about censorship, a national hot-button topic. Courts in New York had ruled that the First Amendment did not protect obscene pornography. Courts in Oregon had ruled that censorship was an unconstitutional restriction of free speech. And three students and a professor at the University of Michigan had been arrested for showing an underground film banned in Michigan and New York, Flaming Creatures.

At Notre Dame, the Student Union Academic Commission decided the University could be a place for discussions of censorship, first amendment rights, morality and obscenity. The Pornography and Censorship Conference of 1969 was born.

Student organizers had gained the administration’s confidence after successfully hosting the Sophomore Literary Festival and Collegiate Jazz Festival, and felt they had carte blanche to create provocative academic events, says conference chairman Thomas Schatz ’70. Censorship was but one of several ambitious programs they planned that year, he adds.

“There was never any push back before this event. We were completely free to put this thing together,” remembers Schatz, now a professor of film and executive director of the University of Texas Film Institute. “It was heavily publicized. Students were interested in what we were doing.

“The way we set this thing up was to have voices heard on both sides,” he adds.

Predicted to attract 1,500 attendees, the conference would open with poet Allen Ginsberg on Wednesday, February 5, and run through the following Monday. Participants could attend a performance of Lady Godiva, an off-off-Broadway parody of porn and politics by New York’s Theater of the Ridiculous, as well as films by avant-garde directors such as Andrew Noren and Andy Warhol, with film critics’ commentary after each screening.

Meanwhile, the LaFortune Student Center would house an exhibit of supposedly salacious artwork in an effort to determine the line between art and erotica. An early punk rock group, The Fugs, would play Washington Hall. Elmer Gertz, the civil rights attorney who in 1964 had managed to lift the United States’ 30-year ban on Henry Miller’s novel Tropic of Cancer, would lecture on the legality of pornography. And a documentary produced by a Catholic group called Citizens for Decent Literature would offer an analysis of Supreme Court decisions regarding obscenity.

It looked to be a balanced and multifaceted conference, but things soon began to unravel.

Part of the problem was that two groups of students were involved in preparing the conference. In one corner were the Student Union organizers, who believed discussions on censorship could be productive and academic. In the other corner were members of the countercultural movement, many of whom were already notorious at the University for protesting when DOW Chemical and the CIA were on campus recruiting. Some in this crew were involved in the acquisition of media for the event, but critics questioned whether their agenda was geared more toward a pornography festival than a fruitful discussion.

At the opening, Ginsberg, while profane, was a hit. But the LaFortune exhibit had met difficulty even before it even reached campus. When the moving company hired to ship some pieces from New York got a look at their cargo, they refused to cross state lines with it. So a crew of students rented a truck and delivered it to South Bend themselves.

Once the display was ready, organizers indicated they were uncertain whether some pieces violated local obscenity laws. While the conference committee debated whether they could show the artwork, a group of 350 people gathered Thursday suggestion to protest its postponement. The exhibit opened and admitted some 1,800 viewers.

By this time, administrators had become uneasy, Schatz recalls. Among their worries was the conference’s potentially embarrassing overlap with the Law School’s centennial anniversary celebration. Invitees to the latter included the deans of 130 law schools, University trustees and Associate Justice William J. Brennan Jr. of the U.S. Supreme Court, who would return to campus later that spring to receive the Laetare Medal as a distinguished American Catholic. Brennan’s 1957 majority opinion in Roth v. United States ruled that the First Amendment did not protect obscene materials, defined as those “utterly without redeeming social importance” or whose “dominant theme . . . taken as a whole appeals to the prurient interest.”

Philip Faccenda ’51, special assistant and legal counsel to Father Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, University president, further feared the ramifications of running films such as Flaming Creatures and Kodak Ghost Poems, especially in the midst of a county pornography crackdown. Should there be indictments, he wondered, who would be held accountable? Administrators? The student organizers? Trustees?

To top it off, the Supreme Court had refused to review New York’s recent determination that Flaming Creatures was “hard core pornography.” And, as former ND English professor Peter Michelson reflected nearly 30 years later in his rendition of the conference’s meltdown for Notre Dame Review, “What New York has found too hideous for consumption is not likely to find sanctuary in Indiana, let alone at Our Lady.” After discussion with University leaders, student organizers announced that both films would be withheld.

Tensions escalated Thursday afternoon, when two different short films were scheduled to play at the Center for Continuing Education. Instead, partial showings of Kodak Ghost Poems and Flaming Creatures occurred, allegedly due to mismarked film canisters, though Michelson’s account suggests this may have been an intentional move by one of the rebel students. A Citizens for Decent Literature representative left immediately to file a complaint with the county prosecutor and the district attorney. Certain that students were going to try to view the films in full, he convinced local police to stand at the ready.

Speaking on behalf of conference organizers, Bill Wade ’69, student union vice president, later explained in a statement to the press that any further showing of films after the “mistake” that afternoon “would do more harm than good” and “detract from the conference and its purpose.” The art exhibit was also closed.

The activists were enraged: The conference on censorship was being censored! David Kahn ’70, a former head of the Notre Dame Film Society and a leader of the campus counterculture group, announced that the films would be screened on Friday, regardless of approval.

Meanwhile, after the Thursday night performance of Lady Godiva, a separate group of students complained to Hesburgh that the play was “gross” and informed him that they planned to protest a second scheduled performance of the play and the screening of Flaming Creatures, apparently unaware that the latter had been canceled. Friday’s Observer published their petition in full. “What students view or present in their own name is their own business,” the petition argued, “but when an event is sponsored in the name of the Notre Dame Student Union Academic Commission and paid for by Student Union funds, it must meet basic community standards.”

Friday afternoon, as Kahn had promised, some 200 students crowded into a classroom in Nieuwland Science Hall to view the forbidden films. As they prepared to show Kodak Ghost Poems, plainclothes police officers burst into the room and demanded the reels. According to The Observer, Saint Mary’s College junior Kathy Cecil grabbed the reels and concealed them under her minidress while other students surrounded the projector. The police reportedly seized the reels from Cecil, dropping her to the ground.

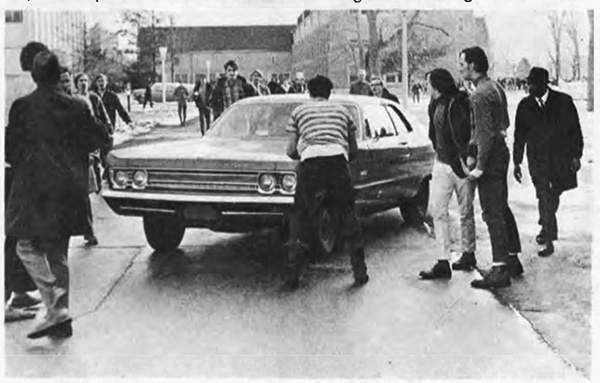

The police quickly exited the scene, forming a barrier of their own around the officer carrying the film. Outside, students grabbed at the reels and walloped the officers with snowballs, shouting “Pigs!” and “Fascists!” Other students lay down on the sidewalk in an attempt at passive protest, but were trampled, though there were no reports of serious injuries.

As the officers neared O’Shaughnessy Hall, the crowd swelled and rushed once more for the reels, knocking the carrier to the ground. Officers retaliated with mace, spraying the eyes of as many as 15 people. The police barricaded themselves inside O’Shaughnessy while protesters pounded at the door, demanding to see a warrant. Sneaking out a back door, the man with the films jumped into an unmarked car that swerved away from the chasing protesters.

“We were scared, as scared as I have seen officers in more than six years,” county prosecutor William E. Voor Jr. later told The Observer. “There were, after all, several hundred of them and only a handful of us.”

It was the first known physical confrontation between students and police in the history of Notre Dame. Prior to the raid, Faccenda had received a warrant to turn over the films. The conference and its organizers were potentially in violation of the law. The District Attorney’s office was reviewing whether to prosecute those involved.

By Saturday, February 8, the conference was off. The remaining events were canceled.

In the days that followed, Father Hesburgh summoned a fact-finding committee composed of students, faculty and administrators. Ironically, the committee’s investigation of the conference started with a viewing of the films with the local prosecutor, recalls Schatz, who was not present at the Nieuwland incident. “It was the damnedest experience I ever had.”

Over the course of the spring semester, Hesburgh’s committee would continue to gather facts, interview participants and decide whether to pursue disciplinary action against anyone involved. In April, the committee recommended to the Student Senate that the University needed to create a clear definition of academic freedom in order to avoid future debacles. Then, in May, it published a 141-page report. The Campus Judicial Board found Dave Kahn and Marty McNamara ’69 guilty of unauthorized use of facilities, assault and battery, and contributing to a public disturbance, but imposed no penalty.

Perhaps the most memorable outcome of the conference was one that rolled it back into the general backdrop of campus unrest: a letter dated February 17, 1969, that Father Hesburgh wrote to faculty and students and published in The New York Times, drawing the respectful attention of the leaders of other universities and President Richard Nixon. It included one of the most famous decisions of Hesburgh’s 35-year presidential career.

“This letter does not relate directly to what happened here last weekend, although those events made it seem even more necessary to get this letter written,” he noted. The letter acknowledged the validity of those student protests that do not disturb the routine of the University or the rights of its members. However, Hesburgh wrote, those who substituted force for rational persuasion, “be it violent or non-violent,” would have 15 minutes of meditation to cease and desist before the University took action against them.

Student dissent never again reached the level seen with the Pornography and Censorship Conference, but it did continue. The war dragged on. Race, environmentalism and sexuality kept campus roused for many years to come.

This winter, campus hosted another, much smaller pornography conference. Sponsored by the Students for Child-Oriented Policy in conjunction with the Tocqueville Program for Inquiry into Religion and American Public Life, “Pervasive Porn” explored pornography’s personal and social costs. It proved less controversial than the first.

Tara Hunt is an associate editor of this magazine.