Years before Guardians of the Galaxy unexpectedly charmed its way across the silver screen — before the movie made $774 million, the biggest film of last summer, starring a gun-toting raccoon and a talking tree named Groot who repeated “I am Groot” in Vin Diesel’s voice — the galaxy’s unlikeliest heroes first entered the imagination of an editor at Marvel Comics named Bill Rosemann.

One night in the winter of 2006, Rosemann ’93 was sitting on his living room floor, searching the Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe for existing Marvel characters he could cobble together to form a new team of cosmic heroes. He already had the team’s name — Guardians of the Galaxy debuted in 1969, albeit with different faces. When he rediscovered Rocket Raccoon, a jetpack-wearing space raccoon irreverently named after a song off the Beatles’ White Album, it seemed like a good place to start.

“With the Guardians, I wanted to have a group of misfit toys,” says Rosemann, now a creative director in charge of storytelling at Marvel’s video games division. “The universe will look at them and say, ‘_You’re_ gonna save us?’ And they’ll say, ‘Yes, we are. We’re the best you got.’”

When Marvel published the rebooted 2008 Guardians of the Galaxy comic edited by Rosemann, fans hailed it as an instant classic. The movie — critics predicted it’d be Marvel’s first flop — was so hilarious and lovable that Marvel editor-in-chief Joe Quesada singled out Rosemann for applause at the company’s advance screening.

“The reason this movie was such a hit around the world — it had a great script, great collection of actors, awesome director, great special effects, Marvel’s characteristic humor — was because at its core it was about family,” says Rosemann, who lives in California with his wife, Ali, and 6-year-old son, Peter. (His son, not coincidentally, shares his first name with Spider-Man and Star-Lord.) “Even though you’re millions of miles away from Earth, it’s centered in very human emotions. It’s something that everyone can relate to. Having a family. Not having a family. Forming new ones.”

Like Spider-Man and Star-Lord, Rosemann’s origin story grows out of familial fragmentation. When he was in high school — shaving, driving, asking girls out — his parents divorced. Rosemann turned to the comics he had read since he was little, seeking solace in the stories of put-upon heroes trying to eke out wins against seemingly invincible foes. Underdogs like him.

Then, like all heroes, he faced a reckoning. In the summer after his freshman year at Notre Dame, an apartment caught fire on the far side of the building where Rosemann lived with his mother in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Rosemann and his mother dashed in and out, salvaging the irreplaceable as the flames edged closer to their unit. On his last trip — smoke thickening, power off — Rosemann hefted a long, heavy box from under his bed and burst into the clear. His comics.

“Whether I realized it or not at the time, those were my origin moments,” he says. “To me, that’s like Batman when the bat crashes through the window and he says, ‘That’s it. I shall become a bat.’”

Rosemann vowed to become a creator of the books that had, in a sense, saved him. In his senior year, he teamed up with such fellow Observer denizens as Monica Yant ’93 and Jay Hosler ’95Ph.D. to create the comic book Wired. Black and white, three stories, 24 pages, built of ink and pulp and imagination.

“Whenever we were together, we would spend a long, long time talking about comics,” says Hosler, who drew and wrote one of the three stories in Wired. “Bill was always somebody who was very interested in multiple facets of the medium, including production, and how it is that you work with a collaborator.”

Rosemann was raised on Marvel’s classic street characters — the heroes who bad guys tried to stuff in Bronx dumpsters — but his repertoire as an editor spans the Marvel universe. Go read Mystery Men, the Depression-era fedora-noir series in which a motley assemblage of costumed weirdos battles a Nazi plot to take over the world. Read Guardians of the Galaxy, in which our familiar team of castoffs and underdogs — one of them a telepathic dog — battles a reincarnated berserker death titan across alternate universes. Go read Marvel Zombies 3.

Weird stuff, right? Rosemann thought so, too, when Quesada asked him in 2007 to edit Marvel’s “cosmic” books. (“A lot of old men in beards with staffs, floating in space and talking.”) But if Rosemann has a singular editing trademark, it’s his eye and ear for crafting characters with heartbeats in rhythm with their audiences’ pulse.

“Bill is a traditional storyteller, which can be something of a lost art,” says Ralph Macchio (not the Karate Kid actor), a Marvel veteran and decades-long friend of Rosemann’s. “He understands that the hero always has to be put-upon, always at the brink of disaster and then has to make his comeback.”

Rosemann’s heroes question the absurdity of fighting nightmarish monsters from alternate dimensions. They sob when their loved ones fall in battle. They doubt their heroism, bicker like co-workers, dance, fall in love. And we, the people watching the movies or reading the books or playing the games, look at them and say: That’s me. That’s my family. I am Groot.

Rosemann points out that Marvel’s new wave of heroes comes in colors besides green. Miles Morales, who is black and Latino, dons the iconic suit in the Ultimate Spider-Man series. The new Thor is a woman. And Marvel’s single most popular new title worldwide is Ms. Marvel, featuring a Muslim Pakistani-American from Jersey City named Kamala Khan. Does he get hate mail for it? Unfortunately, yes. But Rosemann also gets letters from kids saying, “Thank you, thank you, thank you, for a Spider-Man who looks like me.”

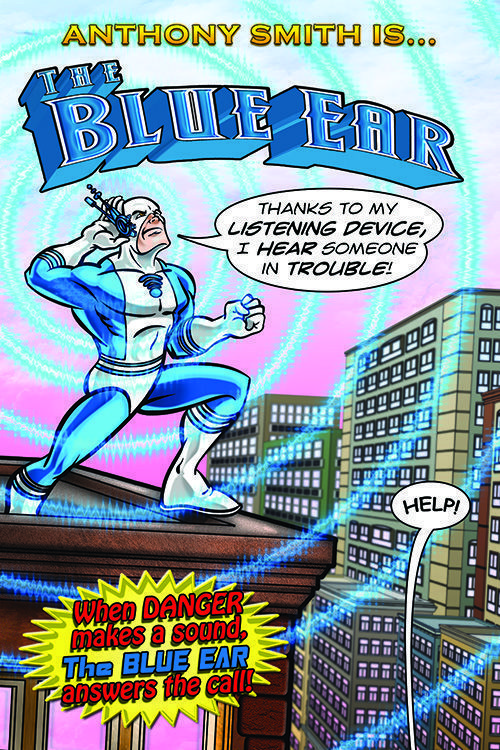

Enter Blue Ear. In 2012, a New Hampshire mother emailed Marvel’s team, asking for help convincing her hearing-impaired son to wear his “blue ear” hearing aid. (“Superheroes don’t wear hearing aids,” the 4-year-old insisted.) Rosemann, who was then part of the Marvel team that developed custom marketing for business partners, forwarded the request to Marvel’s Heroes group. Artists Nelson Ribeiro and Manny Mederos responded with artwork of a hero called Blue Ear, who listens for danger with a specialized hearing aid.

Blue Ear caught on fast among hearing-impaired kids, and Rosemann says he still fields emails from parents and teachers looking to share the artwork with their kids. In 2014, his old team produced the comic Ironman: Sound Effects for The Children’s Hearing Institute. It features Iron Man and Blue Ear as well as a new female character, Sapheara, who has bilateral cochlear implants.

Blue Ear and Kamala Khan are symbols that Rosemann’s calling has become his cause. By day, he’s developing new stories for Marvel’s video games — a much larger audience, he notes, than traditional pulp. By night (besides family duties), the hero-maker gives talks at schools and universities around the United States, trying to, well, make heroes. Find what the world needs, he tells the assembled students. Find your power. And use it virtuously. We are Groot.

“We’re showing that heroes can come from all walks of life,” he says. “Everyone can be a hero. We can use this to inspire everyone . . . to be a better version of yourself.”

Michael Rodio is a writer from New Jersey and an editor at NBC in New York City.