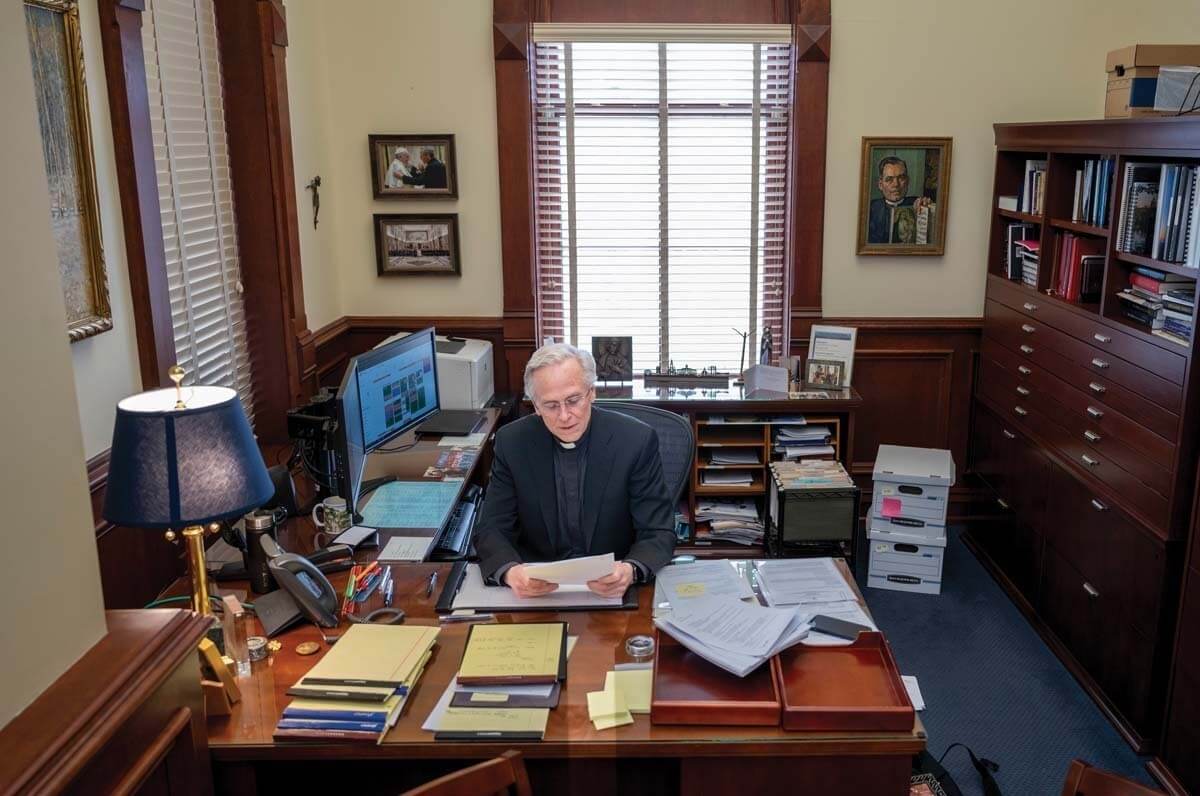

On the wall in the elegant office suite known by the modest address of 400 Main Building hang the framed portraits of 16 priests.

They are the priests of the Congregation of Holy Cross who founded a college in the Indiana wilderness, who saved the young school from ruin after a devastating fire, who admitted a gifted student-athlete named Knute Rockne, who locked arms with Martin Luther King Jr. in service to civil rights. They are the priests who had the vision to build and sustain the premier Catholic university in the United States. They are the priests who have served, since 1842, as presidents of the University of Notre Dame.

In time, a 17th portrait will be placed on the wall. Rev. John I. Jenkins, CSC, ’76, ’78M.A., who has led Notre Dame since 2005, will step down as president on June 1, to be succeeded by Rev. Robert A. Dowd, CSC, ’87, the vice president and associate provost for interdisciplinary initiatives who also serves as an associate professor of political science.

It is a time for transition, a time for assessment at Notre Dame.

By the numbers, Notre Dame has experienced tremendous growth in size and stature during the 19 years of Jenkins’ leadership.

In 2005, 15 percent of Notre Dame’s admitted students ranked in the top 1 percent on national test scores and just over 60 percent were in the top 5 percent. Compare that to 2023, when 54 percent of Notre Dame’s admitted students scored in the top 1 percent and nearly 90 percent were in the top 5 percent. Over Jenkins’ tenure the median SAT score among incoming freshmen has risen from 1410 to 1500.

The University reports an applicant acceptance rate in 2023 of 11.9 percent, the lowest in school history.

So, yes, alumni, you probably couldn’t get in now.

The University has grown as a research center, reaping more than $200 million a year in new research funding. Last year, Notre Dame was invited to join the elite Association of American Universities (AAU), which includes 69 of the nation’s leading research schools and two more in Canada.

Notre Dame’s international presence has expanded. The University reports, for instance, that 1,829 students coming from more than 100 countries studied at Notre Dame last year. That’s roughly twice the number of international students from 2005.

Athletic success remains a signature. Notre Dame has won 10 NCAA championships — in fencing, women’s basketball, men’s lacrosse and soccer — on Jenkins’ watch.

So, the numbers are impressive. Alums who visit Notre Dame will notice a transformation of the architectural footprint on and around campus as well.

The most significant achievement in Jenkins’ tenure, though, is something less tangible. It amounts to a promise kept.

In his inaugural address in 2005, Jenkins said: “There are certainly other truly great universities in this country. Many of them began as religious, faith-inspired institutions, but nearly all have left that founding character behind. One finds among them a disconnect between the academic enterprise and an overarching religious and moral framework that orients academic activity and defines a good human life.”

Then he made the promise: “My presidency will be driven by a whole-hearted commitment to uniting and integrating these two indispensable and wholly compatible strands of higher learning: academic excellence and religious faith.

“Building on our tradition as a Catholic university, and determined to be counted among the preeminent universities in this country, Notre Dame will provide an alternative for the 21st century — a place of higher learning that plays host to world-changing teaching and research, but where technical knowledge does not outrun moral wisdom, where the goal of education is to help students live a good human life, where our restless quest to understand the world not only lives in harmony with faith but is strengthened by it.”

He has made good on that inaugural promise. Notre Dame has affirmed its status as a place that vigorously embraces open inquiry and unfettered debate. It has, at the same time, retained its essential Catholic identity and purpose.

That hasn’t always been easy. And not everyone would say the dual ambitions have been met. Over these 19 years, the status of Notre Dame’s identity has at times been furiously challenged.

“Notre Dame remains an unapologetically Catholic university. Chapels in the dorms, things like that, remain a big part of the essential nature of the place,” says Don Wycliff ’69, a retired journalist. “Starting with Father [Theodore] Hesburgh and [Father Edward] Monk [Malloy ’63, ’67M.A., ’69M.A.], and continuing with Father Jenkins, Notre Dame has taken a strong stand for open inquiry. That is the way Notre Dame has served Catholicism best. There are some people who disagree, just as there are some people who never made peace with Vatican II. But there is no going back.”

Notre Dame’s commitment to open inquiry and academic freedom dates at least to 1967, when leaders of the University and several other Catholic institutions met at Land O’Lakes, a Notre Dame retreat in Wisconsin. They released what is known as the Land O’Lakes Statement, which is viewed, not always approvingly, as a declaration of independence from the Church hierarchy.

The statement reads in part: “To perform its teaching and research functions effectively the Catholic university must have a true autonomy and academic freedom in the face of authority of whatever kind, lay or clerical, external to the academic community itself.” This became its most controversial passage.

In a 2017 essay in the Jesuit magazine America, Jenkins cautioned against placing a narrow focus on that passage, and he also pointed to shortcomings in the statement that had become evident over time. In particular, he focused on how the statement should guide, not command, the unique nature of Notre Dame.

“Critics of the Lakes statement insist it initiated, intentionally or unintentionally, a slide toward secularism. But what the document actually envisions, rather ambitiously, is a university whose Catholicism is pervasively present at the heart of its central activities — inquiry, dialogue, teaching and human formation,” Jenkins wrote. “The internal dynamic of these activities, as they saw it, would lead to God and to a consideration of all things in relation to God, and these activities would take place in a community of faith redeemed and transformed by Christ.”

Since Land O’Lakes, some universities have largely shed their Catholic identity. Jenkins assured that Notre Dame has charted its own path.

“There is an odd, ironic kind of conformist tendency in higher education, because it’s sort of reputation driven. You want to be like Harvard or Yale or whatever, the great institutions,” Jenkins says in an interview. “I’m not diminishing them at all. But I felt Notre Dame had to have a different role. To remain distinctive, not in a reactionary way or in a sectarian way. But to have a different kind of mission because of its Catholic character. . . . But frankly, if you’re different and you’re not very good, nobody cares. I think we remain distinctive.

“If you look at our strategic framework, what are we focused on? We’re focused on strengthening democracy, on poverty, climate change, ethics. All of those have a resonance because of the Catholic mission, and I think people say that’s a valuable place to be. I think the progress I’m most proud of is that, whether you’re of faith or not, we’ve got a mission here, and it’s different, and that mission is an asset and not a problem.

“There’s also a certain humane character to this place, a certain compassion, care for our students.”

Jenkins is firm in his belief that the invitation to Obama, which stirred such intense political and moral debate, affirmed Notre Dame’s mission. “To be a great university, you have got to have open inquiry,”

Notre Dame’s rising stature during Jenkins’ tenure has drawn the attention of nationally recognized leaders in higher education.

“He took it to the next level, standing on the shoulders of those giants who came before him,” says Morton Schapiro, who served 13 years as president of Northwestern University before stepping down in 2022. “The undergraduate selectivity, the research profile: I don’t imagine anybody would have thought Notre Dame would be where it is today on John’s first day.

“Now it has become a research power, without losing focus on high-quality education. Notre Dame got into the AAU. The AAU is the exclusive club everyone wants to be in. Hundreds of universities call themselves research universities, but unless you’re one [of the AAU members], you don’t have the stature.”

“He’s so warm and gracious,” Schapiro adds. “He always seemed unflappable, which is really important when you have people screaming at you from all sides. He has led with morality and put God at the forefront. He has been a model leader . . . with the greatest integrity.”

Defining and defending the culture and mission of a college campus have become far more difficult in recent years as schools, and the nation at large, have been engulfed by political and cultural wars. Many universities have declared their support for free speech and unfettered debate yet have adopted speech codes, refused to allow certain speakers on campus because of their beliefs, and attempted to codify accepted values.

Notre Dame has hardly been immune to such difficulties. The most dramatic challenge to Jenkins’ tenure came in 2009, when Notre Dame invited President Barack Obama to deliver the University’s commencement address and receive an honorary doctorate of laws. Notre Dame had established a tradition of inviting U.S. presidents in their first term to speak at commencement; Obama would be the sixth president to give a commencement address and the ninth to receive an honorary degree.

But the invitation to Obama prompted outrage from many Catholics and pro-life organizations. They demanded the invitation be rescinded because of Obama’s support for abortion rights and federal funding for embryonic stem cell research. The bishop of the Fort Wayne-South Bend diocese refused to attend the ceremony, in a break with another tradition. The president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Cardinal Francis George, declared that Notre Dame had caused “extreme embarrassment” to the Catholic faithful. Off-campus protests lasted for weeks, and tens of thousands of people signed a petition denouncing the invitation.

The pressure peaked on commencement day. Dozens of protesters were arrested outside the convocation center. Several graduating students and others attending the ceremony marched out in protest. More than 20 students held an alternative commencement ceremony. Many people questioned whether Notre Dame had repudiated its Catholic identity by honoring Obama.

It was, Jenkins recalls, the hardest moment of his tenure. “I was less experienced, and it came unexpectedly to me,” he says. “I think it was the first salvo in how we’ve become so utterly polarized, and so unable to give any respect to someone who disagrees with us. I think it started with that, and I didn’t expect it, but it has just become worse and made our government near-dysfunctional.”

“He suffered unfairly, tremendously unfairly, for that. I would say he toughened up a bit. He had to,” says Michael Pollard ’76, a retired attorney from Chicago who has known Jenkins since they were undergraduates.

“The University is more of a force for good now than it was when he started,” Pollard says. “It is a nurturer of moral wisdom for its students. That is still at the heart of the institution. That maybe is the ultimate testament to him. You are educated in character as well as technical knowledge. He has turned moments of controversy into teachable moments for students, staff and alumni.”

Today, Jenkins is firm in his belief that the invitation to Obama, which stirred such intense political and moral debate, affirmed Notre Dame’s mission. “To be a great university, you have got to have open inquiry,” Jenkins says. “If you believe that God is true, God created the world, God gave us minds to understand truth, you should not be afraid of open inquiry. You just shouldn’t. It could be done irresponsibly. You have to make sure it’s the right form. But I am utterly committed to that, and utterly committed to Notre Dame playing that role.

“Now, as far as the Catholic mission, and the Catholic Church and Catholic hierarchy, I do think Notre Dame’s the flag you want to capture, left and right. That’s why we get all the heat from whatever side, particularly the right. I respect the bishops; they have a very hard job. They’re kind of pressured on a lot of fronts.”

Two presidents have been elected since Obama’s tenure. Neither has given the commencement address at Notre Dame. Joe Biden, as vice president, and Republican House Speaker John Boehner were presented with the Laetare Medal at commencement in 2016. Vice President Mike Pence, a former Indiana governor, was invited to speak at commencement in 2017 rather than Donald Trump. Dozens of graduating students walked out as Pence rose to give his address.

Jenkins explains the decision-making in the wake of the Obama controversy. “I was committed not to be partisan, but the elected leader of the country, that’s important. So, with Boehner and Biden, that was intended. So to say, look, these are two Catholics who are leaders in our country, and we are not favoring a party, but we’re favoring their leadership. . . . I want to say that, regardless of one’s political views, if you’re the elected leader of the country, we invite you to Notre Dame. However, if you don’t meet a certain bar in terms of just moral decency, that’s why we invited Mike Pence. There’s a decency, I think. A genuine decency.”

Other debates tested Notre Dame and Jenkins, too. In his first year as president, Jenkins launched a dialogue with students and members of the faculty and staff about on-campus performances of The Vagina Monologues, a play that deals with sexuality and identity in graphic terms. The play had been performed on campus in previous years, drawing criticism. Jenkins sought a teaching moment. After 10 weeks of discussions, he issued a statement on academic freedom that said the play’s “portrayals of sexuality stand apart from, and indeed in opposition to, Catholic teaching on human sexuality,” but performances could continue.

“I am very determined that we not suppress speech on this campus,” he wrote. “I am also determined that we never suppress or neglect the Gospel that inspired this University. As long as the Gospel message and the Catholic intellectual tradition are appropriately represented, we can welcome any serious debate on any thoughtful position here at Notre Dame.”

More recently, controversy erupted over the performance of a drag show on campus as part of a class called What a Drag: Drag on Screen — Variations and Meanings. In a letter to The Observer, the primary student newspaper, two Notre Dame seniors wrote: “A drag show absolutely constitutes the harassment of women. In drag across the country, biological males dress in provocative women’s clothing and portray sexual violence for the sake of entertainment. Nowhere else in our nation do we accept misogynistic sexual stereotyping and objectification as something to be celebrated. . . . If this is academic freedom, then the phrase is meaningless. Women are harassed, objectified and mocked through events at a university that claims to be dedicated to the pursuit of truth and protection of human dignity. The line has been crossed.”

The University administration, however, determined that the drag show, because it was part of a course curriculum, was permissible as a matter of academic freedom.

Those who work most closely with Jenkins describe him as quiet, pastoral, contemplative, even introverted, but also as an inspiration for his collaborative style and decisiveness.

“The University is a much better university than it was when he took office,” says Ann Firth, ’81, ’84J.D., a University vice president and Jenkins’ chief of staff. “Lots of people have been part of that, but no one better than he to live with and articulate some of the tensions we experience and to be true to our Catholic identity. He’s shown remarkable courage and equilibrium. He has been able to advance the institution in extraordinary ways.

“He does it with a real heart of service,” Firth says. “So many occasions he’s had a very long day, might be tired, but a student wants to talk to him about something and his generosity of response is so amazing. It’s quite powerful. There’s a hunger for holiness, for heroes. It’s quite moving to see how people respond to him.”

“He takes time to listen,” says Elizabeth Boyle ’20, ’23MGA, who served as student body president in 2019-20 and stays in touch with Jenkins. “We have had some intense dialogues about peace initiatives. For him, peace is a personal issue.” Boyle is now an international relations officer in Rome for the Community of Sant’Egidio, a lay Catholic association focused on peace, prayer and serving the poor. “I hope I have a friend for life,” she says.

To be president of a major university is, in some measure, to be mayor of a city. The role comes, like it or not, with a constant spotlight. One example: the crisis prompted by what Jenkins, with a laugh, calls “the dumbest decision of my life.”

In September 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic raged, Jenkins accepted an invitation to attend President Trump’s announcement that he was nominating Amy Coney Barrett ’97J.D., a law professor at Notre Dame, to succeed the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the U.S. Supreme Court. The attendees at the Rose Garden event were tested for COVID as they arrived. Jenkins and others, though, did not wear masks during the outdoor ceremony, which was widely viewed on television.

Jenkins self-isolated when he returned to campus, as part of University protocols. But within days, he tested positive for COVID. Notre Dame’s policy called for students, teachers and staffers to wear masks and practice social distancing in crowds, neither of which Jenkins had done at the White House.

The episode sparked the most intense challenge to his leadership since the Obama invitation. Some students accused Jenkins of hypocrisy and launched a petition drive demanding his resignation. Some professors called for a vote of no confidence in his leadership, and the Faculty Senate narrowly headed it off.

Jenkins apologized to the University community for not abiding by COVID safety rules. Reflecting on the episode, he rues getting caught up in what he describes as the White House’s COVID-related “manipulative political theater.”

Jenkins seems confident in Notre Dame’s future, confident that Notre Dame, in a time of turmoil on many campuses, will maintain its clearly defined mission.

The Rose Garden episode aside, University leaders are proud of how they responded to the COVID threat. The University quickly canceled in-person classes and called home students studying abroad as the pandemic hit in early 2020. Spring break was extended for a week, then virtually all students stayed home and the rest of the semester was conducted with online learning. Students could receive a grade or credit for courses. On-campus research was suspended. Masses in the basilica were offered by livestream only. Commencement was conducted online. Campus life essentially halted.

The decision, though necessary under the initial lockdown, didn’t sit right. “Father John said, ‘This isn’t what we do, this isn’t who we are,’” recalls Firth. The University, arguing that education is best done in community, moved quickly to plan a return to in-person learning in the fall. Jenkins announced in May that the campus would reopen early in August for in-person learning — far sooner than most universities did.

“The pivotal question for us individually and as a society is not whether we should take risks, but what risks are acceptable and why,” Jenkins wrote in a May 2020 op-ed in The New York Times. “Disagreements among us on that question are deep and vigorous, but I’d hope for wide agreement that the education of young people — the future leaders of our society — is worth risking a good deal.”

The administration adjusted the academic calendar to start the fall 2020 semester weeks earlier than usual, canceled fall break and finished the term by Thanksgiving, reducing student travel. The school consulted with local and national health experts and established detailed protocols to limit the spread of the virus. The plans were upended by rising COVID case numbers almost as soon as students returned to South Bend, prompting an Observer editorial with the stark headline: “Don’t Make Us Write Obituaries.”

The University soon announced a shift to online learning for at least two weeks. But as cases subsided, the school went back to in-person learning. People close to the decision-making say Jenkins was determined to resume in-person learning as quickly as it could safely be done. “He empowered us” in the decision-making process, says Marianne Corr ’78, vice president and general counsel. “It was collaborative, but not in a paralyzing way. It was exhilarating. He’s very pastoral, but he has a spine of steel.”

“He was confident enough to listen and let the decision unfold,” says Firth. “He’s incredibly disciplined in his decision-making. He’s a person of courage. He came through these crises with a lot of courage.”

Rev. Thomas Blantz, CSC, ’57, ’63M.A., history professor emeritus and author of The University of Notre Dame: A History, compares Jenkins’ leadership on COVID to that of Notre Dame’s founder, Rev. Edward Sorin. Jenkins “did a great job with that. There’s an author who said of Sorin, ‘If he hadn’t been a priest, he could have been a riverboat gambler.’”

Perhaps the last bit of a COVID gamble on campus took place at, of all places, Notre Dame Stadium that November.

Football also had to adjust for COVID. Crowds at Irish home games wore masks, kept socially distanced and were limited to 20 percent of stadium capacity. Notre Dame played Clemson, then the top-ranked team in the country, for the last home game before students would leave campus for winter break. Notre Dame won the game in two overtimes and the students — on national TV — stormed the field, and not exactly in a social-distancing manner.

The moment spoke to the risks of COVID — and to the storied enterprise of athletics at Notre Dame, an enterprise that itself could be at risk. Jenkins places the future of athletics high on the list of unfinished business that will confront his successor.

Notre Dame plays at the highest levels of 26 varsity sports, both on the field and in the boardroom. The school and NBC announced last November that their agreement to broadcast Notre Dame home football games, launched in 1991, had been extended to 2029. But Notre Dame has always embraced sports as part of its academic mission, and collegiate athletics, particularly football, are heading in a direction that doesn’t necessarily serve that mission.

Notre Dame has supported efforts to allow student-athletes to receive compensation for the use of their names, images and likenesses, which has been lucrative for higher-profile athletes. But Jenkins says that, without changes from Congress and the NCAA, college sports are in danger. At risk for Notre Dame in particular is its historic identity in sports.

“Notre Dame’s story is overcoming odds . . . overcoming obstacles and working together. And I think that’s part of the culture of the place. It’s a story that resonates with people,” Jenkins says. “I wouldn’t be interested, as president, in having a professional sports franchise. I don’t see how that fits our mission. It has to serve the educational mission of the institution. This effort to be competitive at the higher level — we are under ever-greater strain.”

But that will be a challenge for Father Dowd.

The pressure will soon be off Jenkins. He plans to take a one-year sabbatical to reflect, to catch his breath, then return to teaching in the Department of Philosophy, where he has been on the faculty since 1990. The author of Knowledge and Faith in Thomas Aquinas, he is giving some thought to how he would approach more frequent writing.

His tenure has been marked by “his complete and unwavering focus on the mission of the place and its purpose and his ability to balance the needs and desires of all the various constituents,” says Corr.

“Under his leadership you have a great university,” says Jay Brockman, director of the Center for Civic Innovation, who joined the engineering faculty in 1992. “The whole succession of leadership since I’ve been here has been in the direction where the University and the community move forward together, hopefully in a way that can serve as a model for other communities.”

Jenkins seems confident in Notre Dame’s future, confident that Notre Dame, in a time of turmoil on many campuses, will maintain its clearly defined mission. “I think Notre Dame’s contribution in the Catholic Church . . . is this combination of the highest level of intellectual inquiry and artistic expression,” he says. “You can do that. You can be at the highest level of intellectual inquiry and cultural expression with this religious reality, this global religious reality.

“One of the great strengths of Notre Dame is we have a broad and rich moral framework that guides the institution and guides our decisions. You can’t be afraid to be distinctive, coming out of that Catholic mission and the richest understanding of what that means.”

So, through all the challenges, what’s the strongest evidence that Jenkins kept his 2005 promise? Perhaps this: “Religion does permeate the place,” Father Blantz says. “The world around us certainly doesn’t question we’re a Catholic university, and it’s well deserved. Can it be perfect? It can be better. We’re not going to be perfect until we get to heaven.”

Bruce Dold is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and the former publisher and editor-in-chief of the Chicago Tribune.