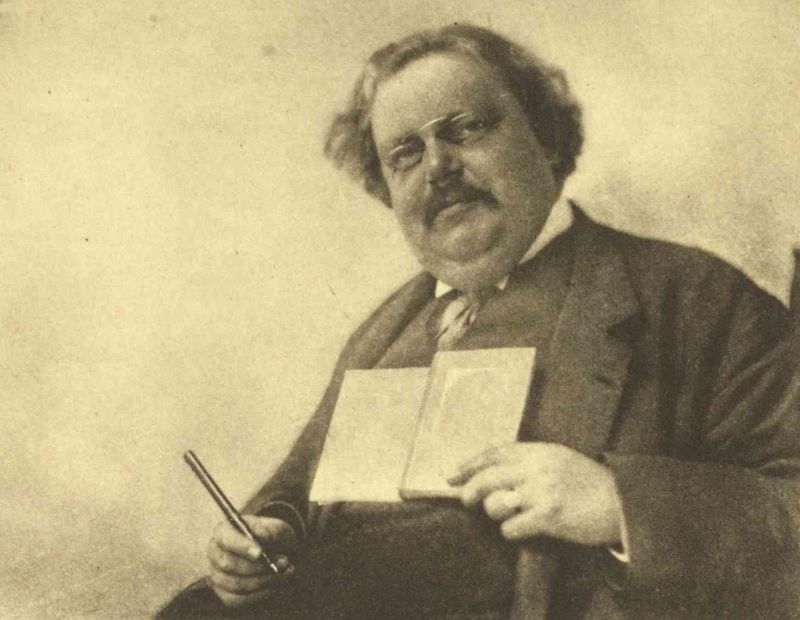

Editor’s Note: Earlier this year, Notre Dame’s London Global Gateway announced the acquisition of the G.K. Chesterton Library. In 1994, English professor Thomas Werge wrote this reflection about Chesterton, the acclaimed Catholic author from England whose global popularity was such that, as a visiting professor in 1930, he received “an uproarious standing ovation” at the game dedicating Notre Dame Stadium.

For Pope Pius XI, G.K. Chesterton was a glorious defender of the church. For C.S. Lewis and Dorothy Sayers, Chesterton’s was the resonant Christian voice that assaulted modern skepticism and championed the faith in a lost and jaded England. His friend and intellectual antagonist, George Bernard Shaw, admired his intellect, wit and integrity.

More recently, cultural commentator Garry Wills praised Chesterton’s “lifelong response to the threat of insanity and destructive intellection.” Wills added that Chesterton, for all his merriment, “was a nemesis of intelligence in a breaking storm of madness.”

The madness, of course, continues apace. From the Hitlers and Stalins of Chesterton’s latter years through today’s shameless exploitation of violence in popular culture streaks a line of insanity. Talk show hosts interview parricides. A comic book features Jeffrey Dahmer’s cannibalism. A lawyer for a teenage murderer peddles her story to television so she can make bail to attend her high school graduation. The mother of a high school cheerleader, wanting to enhance her daughter’s popularity, plots the murder of a rival cheerleader, providing yet another plot for yet another made-for-TV movie.

Consider the media-celebrated cases of Amy Fisher and Joey Buttafuoco, Eric and Lyle Menendez, Lorena Bobbitt and Tonya Harding, and the truth of Chesterton’s seven-decades-old claim still rings loud and clear: “The modern world is madder than any satires on it.”

Our era’s talk-show psychoprattle sprouts like dissonant assaults on the mind and ear led by Mad Hatters with microphones. Our most visible self-image may or may not be that of an “idiot culture,” as Carl Bernstein puts it, but idiocy certainly has all the most valuable advertising space (although it was the journalists at one major national newspaper who banned the word “normal” as being too offensive — presumably to all alleged “abs”). Too often this idiocy claims the moral high ground when, in fact, it is simply bad faith, confusion and profit motive: Silliness sells.

But when “modern” comes to mean an inability or unwillingness to make moral judgments and to act responsibly, the truths of tradition and faith — what T.S. Eliot called “the permanent things” — must again be given voice.

In one of his novels Evelyn Waugh described a teacher of the classics whose position is at risk because parents want their children to qualify “for jobs in the modern world.” When the headmaster asks the teacher, Scott-King, whether he can blame them for doing so, the teacher replies assuredly, “Oh yes, I can and do, I think it would be very wicked indeed to do anything to fit a boy for the modern world.” Told by the headmaster that his view is short-sighted, Scott-King responds, “I differ from you profoundly. I think it is the most long-sighted view it is possible to take.”

If Samuel Johnson was right in stating that human beings do not need to be instructed so much as they need to be reminded, then Chesterton, like Scott-King, serves to remind.

Born in 1874, Gilbert Keith Chesterton entered a world inflated with the bravado of seemingly limitless technological and industrial promise. It was a culture heady with its own power and with the conceit of human and social evolution, while simultaneously adjusting from the dispiriting view of the human as animal, automaton, or slave — a victim of social and psychological forces. It was a “modern” world, one abandoning old stories, myths, and mysteries in favor of a fashionable secularization.

As a bright, witty, and absent-minded youth, Chesterton was once described as “six foot of genius.” Claiming in his adolescence to be pagan and agnostic, he attended art school but was attracted to writing and, eventually, to religious faith. He married Frances Blogg, an Anglican, in 1901, and two years later an attack on Christianity by a newspaper editor triggered Chesterton’s refutation. From then on GKC, as he was most often known, became a powerful Christian apologist, praised for his impassioned faith, intelligence and integrity.

But his journey to faith was not without detours. GKC’s description of Saint Francis may also describe himself: “He was not a mere eccentric because he was always turning toward the centre and heart of the maze; he took the queerest and most zigzag short cuts through the wood, but he was always going home.”

Although Chesterton’s childhood home was largely agnostic, he defended the institution of family against the Marxists who distrusted its power and against the familophobes who accused it of dysfunctionalism. “It is, as the sentimentalists say, like a little kingdom,” he wrote. “And, like most other little kingdoms, is generally in a state of something resembling anarchy.”

Its wholesomeness, for him, lay precisely in its divergences: “Aunt Elizabeth is unreasonable, like mankind. Papa is excitable, like mankind. Our youngest brother is mischievous, like mankind. Grandpa is… old, like the world.” Families are large, not narrow, he reminded. They are richly varied, not uniform; and even when they exasperate us, we are to glory in their diversity. “The men and women who, for good reasons and bad, revolt against the family,” he wrote, “are, for good reasons and bad, simply revolting against mankind.”

Chesterton’s belief in mankind, Garry Wills once wrote, was derived from a profound sense of “pietas, the reverence for one’s ancestors, one’s earth, one’s contact with being on all sides.”

Chesterton dedicated his classic Orthodoxy to his mother, who guided him into the mystery of Being’s order and the sanity of adventure. “I remember with certainty,” he recalled, “this fixed psychological fact: that the very time when I was most under a woman’s authority, I was most full of flame and adventure. Exactly because when my mother said that ants bite they did bite, and because snow did come in winter (as she said); therefore the whole world was to me a fairyland of wonderful fulfillments, and it was like living in some Hebraic age, when prophecy after prophecy came true.”

For GKC this piety and respect for tradition anchors and deepens, rather than hinders, human rights. America, he once wrote, is a “nation with the soul of a church,” founded on a creed. Its Declaration of Independence expresses with “dogmatic, even theological lucidity” the truth that each individual’s human rights are God-given and not state-bestowed. The state is a capricious master, giving and taking away by the whims of power. Only faith and orthodoxy can point to the ultimate ground of all rights — natural law and nature’s God.

A world-renowned “thinker,” GKC wrote more than 100 books and contributed to more than 100 magazines. He commented on religion, politics, art, eugenics, literature, popular culture -- a multitude of subjects both topical and perennial. He and George Bernard Shaw, his agnostic opponent and good friend, are the most-quoted writers of their generation. Orthodoxy, Victorian Age in Literature and Saint Francis of Assisi continue to be GKC’s most popular works; his essay on humor for the 14th edition of Encyclopedia Britannica remains a classic.

The wisdom, wit and insights he offered early in the 20th century have never been more pertinent than today. For Chesterton, the lunacies of the “modern” world stemmed from an abandonment of moral perspective. To counter the decline toward madness, to reclaim the fallen realm, to anchor a society cut loose from its moorings, he championed the Christian tradition, defending orthodoxy when it was out of fashion. Yet the “romantic Chestertonian orthodoxy,” as F. Scott Fitzgerald called it, was not a staid or stagnant allegiance to the tenets of a lost past, but the paradoxical coupling of an inspired traditionalism with an adventurous embracing of a realized truth and its specific values.

“I had no more idea of becoming a Christian than of becoming a cannibal,” he once reflected, recalling his initial explorations into the faith. “I imagined I was noting certain fallacies partly for the fun of the thing and partly for a certain loyalty to the truth of things.” But the real “truth of things,” he discovered, centered on the Incarnation, the first Christmas story, which, he wrote, reveals and dramatizes “the human instinct for a heaven that shall be as literal and almost as local as a home. It is the idea pursued by all poets and pagans making myths; that a particular place must be the shrine of the god or the abode of the blest; that fairyland is a land; or that the return of the ghost must be the resurrection of the body.”

For Chesterton, only the grounded vision and tenacious faith described in the Apostles Creed could counter the extremes of his age. Only the Incarnation adequately served to guide and anchor a rootless and chaotic world. Then, perhaps as now, egotism, even solipsism, dominated. Ennui and inauthenticity reigned. Despair had become the convention: We have domesticated it, Flannery O’Connor wrote, and have learned to live happily with it.

GKC criticized modern intellectuals for combining “an expensive and exhaustive rationality with a contracted common sense.” He cautioned them against blind faith in evolutionary progress, and he warned those within earshot about what Orwell termed the “smelly little -isms” of our terrible century — pure subjectivism versus materialism, individualism versus collectivism, anarchy versus scientific fatalism.

Surrounded by these politically correct definitions of human behavior, orthodoxy had become a horror. Seen as static and monolithic (like God, or the church, or traditional depictions of human nature), orthodoxy was equated with death by the cultural pundits of Chesterton’s day. Novelty, progress, evolution, change and the nihilistic decrees of modern iconoclasts were the romantic doctrines of a promised new and secular consciousness. Darwin, Marx, Freud and the European philosophers provided new and revolutionary views of the masses. Nietzsche’s “Superman” replaced older visions of God: Scientific and rationalist progress would banish evil and leave traditional Christianity as debris in its wake.

Chesterton’s ancient yet perennial faith, however, was no mere dream of ecstasy. It has lasted for 2,000 years and, he wrote, “the world within it has been more lucid, more level-headed, more reasonable in its hopes, more healthy in its instincts, more humorous and cheerful in the face of fate and death, than all the world outside. For it was the soul of Christendom that came forth from the incredible Christ; and the soul of it was common sense.”

Chesterton knew that without this common sense, both common decency and the worth of common people would be imperiled by tyrants, the arrogant, those who devalue human life. Recalling Nietzsche’s professed disgust and disdain “at the sight of the common people with their common faces, their common voices, and their common minds,” Chesterton anticipated the rise of totalitarianism. He warned against its contempt for the ordinary, prosaic and democratic, as well as its repudiation of the real and commonplace in the name of abstract theory, ideological power and romantic nihilism.

His real fear for humanity stemmed from the romantic irrationality of Nietzsche’s thought. With its proclamation of the Superman “beyond” good and evil, its contempt for traditional morality, its imagery of blood and iron, its dreams of individual autonomy wholly cut off from communality, this perverse vision assumed the spectre of lethal nightmare. As Hitler incarnated his own version of Nietzsche’s vision, GKC saw the beginnings of an apocalyptic destructiveness — a hell on earth — although he did not live to witness its end.

Chesterton died in 1936 as Hitler was assuming power and Stalin was tyrannizing the Soviet Union. But in his lifetime, GKC recognized the evil and violence of which human nature was capable, and he mistrusted any appeal to “the will” when severed from conscience. So he worried about a range of social and political movements, quite noticeably the new worship of technology and its implications for a world where intellectual arrogance and fervent militarism take root in a spiritual void. In this setting, he knew, the cry of progress was a death rattle.

GKC’s ability to locate and strikingly articulate the relevance of faith made him immensely popular and influential among believers. Even as the first rumblings of Hitler’s rise to power were being noticed, he denounced the Nazi regime for its hatred of Jews, Catholics and all minorities. “They commit every crime,” he wrote, and “it is in no partisan spirit that any Chrisitan will smell evil in this vast explosion of gas and wind.”

He scorned eugenics, the theory of “breeding” human beings to form a better “stock,” as a pseudo-science; it was a theory made liberal and horrific in the Nazi experiments. In the social, political, and ecclesiastical realm, GKC delighted in reminding reformers of the virtues of restraint and reactionaries of the virtues of liberalism.

Faith, he once wrote, “is always at a disadvantage; it is a perpetually defeated thing which survives all its conquerors.” This image of faith as afflicted conqueror, scarred but persevering and unbowed, crystallizes Chesterton’s imagination.

Orthodoxy’s real joy as adventure consists of a fidelity that encounters and endures’ all slings and arrows of madness, suffering and evil. By “reascending to origins” — to use T.S. Eliot’s phase — GKC revitalized the Christian vision and the pilgrim church. Though his faith and hope remained luminous, his love abounded as well. Where his detractors viewed the world as a “dreary waste,” he felt a “sacred thrift.” When many philosophers argued that God’s making of the world enslaved it, GKC replied, “According to Christianity, in making it, He set it free.”

The way to love anything, he knew, “is to realize that it might be lost.” The threat of loss compelled him to argue urgently for the moral imagination of the true fairy tale, for the reality of human nature, for the sacramentalism of being and all created things, for the joy of diversity and repetition, and for the mysterious paradoxes of suffering and redemption.

The sheer gratitude that so often marks GKC’s tone testifies astonishingly to the depth of his faith. His playfulness and self-deprecation bespeak a genuine humility. For him, the vicissitudes of topical issues and political battles are finally played out according to their participants’ deepest visions, their most-believed stories.

Our deepest faith, he maintained, shapes our ordinary actions. Although much Christendom had become indifferent toward its orthodox legacy, he insisted that this orthodoxy meant not static torpor but fierce adventure. “People have fallen into a foolish habit of speaking of orthodoxy as something heavy, humdrum and safe,” he wrote. “There never was anything so perilous or so exciting as orthodoxy. It was sanity: And to be sane is more dramatic than to be mad.”

Orthodoxy, he believed, was rooted in the enchanted wisdom of the fairy tale and the ordinary empirical repetitions of the everyday world, thus valuing the commonplace as sacramental and celebrating “the pricelessness and the peril of life.”

A lover of fairy tales as a child, GKC insisted that even though he “left the fairy tales lying on the floor of the nursery,” he had “not found any books so sensible since.” Against contemporary proponents of rationalism and reductive materialism who despised the imagination, Chesterton celebrated its power. The fairy tale, he explained, speaks to the world’s wonder and enchantment and to an insistence on stark limits. In fairy tales the magic of experience combines astonishment with the constraints of moral choice.

“We all believe fairy tales, and live in them.” Stories are what matter and endure. “I had always felt life first as a story,” he explained, “and if there is a story, there is a story-teller.”

In the true fairy tale, as in life, risk and obedience do battle — and people are expected to be responsible for their actions. The consequences remain awesome: “A box is opened and all evils fly out. A word is forgotten, and cities perish. A lamp is lit, and love flies away. A flower is plucked, and human lives are forfeited. An apple is eaten, and the hope of God is gone.”

This statement was written in 1908, 14 years before Chesterton entered the Roman Catholic Church. Even then, the truths of fairy tales and ordinary experiences were part of his religious vision, leading him to the church he called his living and perpetual teacher, the bearer of the story. “We are psychological Christians even when we are not theological ones,” he would later write.

For Chesterton, redemption lay in paradox. Whether exploring the boundaries between body and spirit, ideal and real, heaven and earth, or human and divine, his understanding of life pivoted on paradox — the mystery of truth and the truth of mystery. And it was the exploration, the chase, the adventure that he savored. “The riddles of God,” he once wrote, “are more satisfying than the solutions of man.”

The ultimate drama, the ultimate paradox, is the Christmas narrative. “Divinity and infancy,” he wrote, “do definitely make a sort of epigram which a million repetitions cannot turn into a platitude. Bethlehem is emphatically a place where extremes meet.” He added: “That tense sense of crisis which still tingles in the Christmas story and even in every Christmas celebration accentuates the idea of a search and discovery.”

Bethlehem mediates all extremes — God and humanity, omnipotence and infancy, infinity and finiteness. Here salvation resides. No other story, he insists, “no pagan legend or philosophical anecdote or historical event, does in fact affect any of us with that peculiar and even poignant impression produced on us by the word Bethlehem. No other birth of a god or childhood of a sage seems to us to be Christmas or anything like Christmas.”

In the mysterious resonance of the very word we discover a “strengthening and a repose” rooted in the astonishing wedding of the divine and the human. Here God embraces and sanctifies the limited boundaries of existence. As GKC was always ready to note in confronting the vague abstractions of varied cosmic religions or academic theories, “To love anything is to love its boundaries; thus children will always play on the edge of anything. They build castles on the edge of the sea” and walk on the edge of the grass.

Their reason for this adventuresome habit is at once obvious and profound: “When we have come to the end of a thing we have come to the beginning of it.” This paradox and all the paradoxes of Christianity and existence he found crystallized in the Christmas story, that all-encompassing narrative which provides an image and icon of reconciliation. Through it we associate two ideas usually entirely remote from each other: “the idea of a baby and the idea of unknown strength that sustains the starts.” Our instinct and imagination still connect them in memory even when reason can no longer see the need.

If our life is to be as adventurous as a fairy tale, Chesterton says, we must remember that the beauty of a fairy tale lies in its journeyers possessing a wonder that borders on fear. If we are afraid of the giant, there is an end of us; but if we are not at least astonished by the giant, there is an end to the fairy tale. In the end — and the beginning — we must have “just enough faith” in ourselves to have adventures, and “just enough doubt” to enjoy them completely.

Tom Werge is a retired professor of English at Notre Dame.