Three years ago I faced a dilemma. Sitting in my apartment in a small New England city, I was looking for a ticket to a real metropolitan life.

Manchester, New Hampshire, had given me a great first job, but it felt painfully small. Politicians had promised for years to build a commuter train to Boston, but plans never materialized. And as a lover of cities, I was desperate for skyscrapers, fine dining and museums.

A job offer in South Bend promised but few of those things, yet it sure did offer a train. I would be a South Shore ride away from the kind of metro center I dreamed about.

For most Americans outside the Eastern Seaboard, train travel is a rarity. Amtrak’s services grow spotty in the country’s interior, and the distances in the Midwest and Great Plains make rail a less practical mode of transportation than air.

But a century ago, things looked a little different.

With the advent of electric rail cars at the end of the 19th century, the United States saw a boom in independent, regional trains. These “interurban” lines served major cities, but they linked smaller ones, too — connecting rural towns to one another and hinterlands to their urban neighbors in states from Connecticut to California. At their peak, hundreds of interurban railways crisscrossed the country. The South Shore Line was one of them.

Christened the Chicago, Lake Shore and South Bend Railway, the line launched in June 1908, following nearly the same route at its inception as it does today. On the eastern end, a station on North Main Street in downtown South Bend served customers traveling to Hudson Lakes, Michigan City and Gary. At the western end, a station on Randolph Street in downtown Chicago marked the end of the line. The “downtown to downtown” service caught on quickly once it worked out its early kinks, and by the late 1920s, it had drawn the attention of the men of Notre Dame.

Knute Rockne loaded his 1928 squad onto the train for its trip to play Navy at Soldier Field, and that same year the railway began advertising in the Notre Dame Scholastic. “Our time is yours,” one promo read. Students could “go when you like, return when you like” on the train’s hourly service, and in the dining car they’d find an atmosphere both “clubby and agreeably inexpensive.”

The enticements must have worked. By 1932, the train was labeled an “old friend” to matriculants at Notre Dame, and a decade later, the student magazine promised that a Dillon Hall band would play its “South Shore Shag” at an upcoming concert.

Paid and unpaid plugs for the train dotted the Scholastic’s pages for decades after those first South Shore ads, and by the end of the century, the train stood in a class by itself. Quietly and steadily, America’s interurbans had shuttered since their heyday, driven out of business by automobiles and air travel. But thanks in part to the steady stream of Domers filling its seats, the South Shore chugged along. By the time of its centennial in 2008, it was the last interurban railway still in business.

I ended up getting that job at Notre Dame and, after my move, became a regular on the South Shore. I took the train to concerts and Broadway-caliber plays. I took it to Christmas parties and bachelorette bar crawls—and, when my boyfriend relocated to Chicago, to his place for weekend reunions. By my first summer in South Bend, I was making biweekly trips to the South Shore terminal, where on Fridays the train would speed me to Chicago just in time for date night.

I spent hours on those lake-skirting tracks, and before long I found them not just useful but something close to sublime. On the South Shore, I didn’t have to worry about getting lost or finding parking on a busy Chicago street. I could curl up in those vinyl seats, watch the sun set over soybean fields through the grimy, giant windows and consider how lucky I was to live where urban comforts and wide open spaces could blur together, a simple train ride apart.

Last fall, I finally made my own metropolitan move. I came to Chicago for school and have loved it. The crowded L trains and dingy corner pho shops have sated my city-loving spirit, and I’d be lying if I said I missed shopping at University Park Mall.

But I realized something about the Chicago-South Bend corridor while riding the rails that connect these cities. The South Shore was never a one-way line. City dwellers hopped the train to South Bend just as often as Michianans rode it west — a trend I saw firsthand when Pete Buttigieg’s presidential rallies drew big-city ideologues to St. Joseph County or my five-year reunion had me stuffing my car with friends who’d rolled in on the evening train.

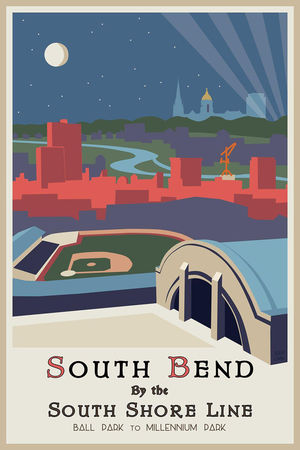

As I prepared to leave my Notre Dame job, I found the perfect poster to commemorate my time in the 574. It hangs today in my Chicago apartment. In a brightly colored illustration, the skylines of Notre Dame and the city it lives in give way to a tagline in old-fashioned script. “South Bend by the South Shore Line.”

My very favorite route.

Sarah Cahalan, a former associate editor of this magazine, is now studying at the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.