“When I was in Mexico with Mother Teresa, she taught me that there are 10 keys to finding inner peace and happiness.”

Certainly that is not the kind of thing you hear very often, but that was how the conversation began between Dr. Paul Wright ‘72, who had been one of Mother Teresa’s personal physicians, and me. At the time, I was working at the Notre Dame Center for Ethics and Culture, and Wright and I were discussing the University’s Medical Ethics Conference, when he blindsided me with the wisdom of the departed saint.

I tore my office apart looking for a pen that hadn’t run out of ink then furiously copied his words down, interrupting every so often with questions like, “Dr. Wright, what was that fifth one again?”

Later I would tell friends about this incident, and they would laugh at the idea of me flailing around my office. Then they would ask, “So what was the fifth one, anyway?” And I’d dig the list out of my backpack and let them copy it down (which inevitably led to more questions and more than a little ridicule of my sloppy penmanship).

A few years later I was working in audio production, and it occurred to me that an interview with Wright talking about his experiences with Mother Teresa in his own words would be much more compelling and much easier to share with people than the crumpled list at the bottom of my bag. Then I started to think that other people in the Notre Dame family might be interested in hearing his story— and in telling their own.

In the summer of 2007, I approached the Notre Dame Alumni Association about the idea, and the Notre Dame Oral History Project was born.

The Oral History Project is rooted in the idea that the Notre Dame story—a composite of powerful memories from Domers and subway alumni alike—not only deserved to be told, it should be recorded, logged and preserved for future generations.

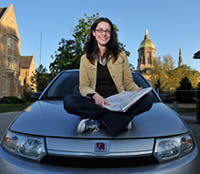

In order to get these interviews, the alumni association agreed to send me on a five-month road trip to talk to Domers all over the country. In autumn 2007, I packed up my car and hit the road.

When beginning a cross-country road trip in October, obviously one of the biggest concerns is the weather. In my case, I also had some health considerations thrown into the mix: In order to prevent my father from having a heart attack, I needed to cross the Rocky Mountains before winter hit.

So when I left South Bend, I headed west. I began with interviews in the Twin Cities and traveled as far west as Seattle. Then it was down to Los Angeles and back east to Fort Lauderdale before ending up in Washington, D.C. I was on the road for five straight months and drove a total of 12,500 miles, stopping to interview 120 Domers in 27 cities.

For the most part, my lodging consisted of the spare rooms and couches of the Notre Dame families who graciously opened their homes to me. The destinations and interviewees were determined by such scientific factors as the weather, word of mouth, the response of the local Notre Dame clubs, my budget and dumb luck.

At first I felt uneasy about this chaotic method, but then my mother pointed out that Notre Dame has thousands of alumni all over the world and I am only one person. Any time I couldn’t interview someone—for whatever reason—I had to remind myself that this was not a scientific study of Notre Dame alumni. Rather, it was an opportunity for people to tell their stories, and I did my best to reach as many people as I could.

My goal at the outset was to collect 100 interviews in about six months. I ended up with 120 in about five—not bad, considering the whole operation ran on caffeine and AA batteries.

Five months is a long time to be on the road, and I was pretty worried before I left. I’ve never been a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants kind of girl; in terms of risk-taking, I prefer to have a Plan Z. And as cool as this road trip sounded in theory, when I sat down and started planning it in September, I struggled to cope with the uncertainty of my day-to-day living arrangements.

Comfort and cappuccino

As it turned out, I needn’t have worried. It’s hard for me to explain the kind of hospitality I received in every city I visited, mostly because I don’t think anyone will believe me. I still hardly believe it myself.

Complete strangers took me into their homes; took me out to dinner; showed me around town; offered to do my laundry or insisted that I at least use their detergent if I wanted to do it myself; comforted me when I had a hard day; and took care of me when I was sick.

They also brought me cappuccino in bed; hooked me up with free tours of national landmarks; introduced me to their Rotary Clubs; warned me about what to do in an earthquake (unfortunately, after the fact); bought me postcards in case I didn’t have time to pick them up myself; taught me how to make lasagna; laughed with me (and maybe a little at me) when I forgot where I parked my car; gave me their maps of national parks and directed me to the most scenic drives; sent me letters and prayed for me. And oh, yeah, they also took at least an hour out of their day to tell me about their lives on tape. All because I was from Notre Dame.

In an odd way, this trip allowed me to experience the sense of the Notre Dame family I was documenting in my interviews. My dad, Fred Freddoso, has been a professor at Notre Dame since I was born, and my relationship with the University has always been “familiar” in the true sense of that word: I think of Notre Dame as another member of my family. It’s always been part of my life, and I love it with all my heart, but I also have a fairly realistic perspective of its virtues and flaws.

Notre Dame has never held a Rudy-esque mystique for me, and it still doesn’t—if anything, my perspective on Notre Dame now is more realistic than before. This road trip wasn’t filled with the ethereal nostalgia of the Grotto at dusk or the Golden Dome gleaming in the early morning sun. Rather, it was filled with innumerable nights when I would show up on a complete stranger’s doorstep in a city I’d never been to before, hungry and exhausted after driving all day, to be greeted with a hug, welcomed inside, shown to a bedroom with clean sheets and towels, and given a meal that had been kept warm for me in case I hadn’t eaten. That’s what my mom does for me when I come home. That’s family.

I now have hundreds of hours of Domers’ stories recorded on tape—stories of their career accomplishments, finding their passion in life, serving in the military, finding their faith, falling in love, raising children, coping with cancer—chronicling their extraordinary everyday lives. But what I found most telling was what didn’t always make it on tape. There was a moment at the end of nearly every interview, just as I was turning off my recorder, when the interviewee would say, “I hope that was good enough.”

The first few times I heard that, I had to laugh, because I’m 27 years old and my greatest long-term aspiration is to have a dishwasher. I can honestly say that I was always impressed with what they said in their interviews. But I soon realized that they didn’t mean “good enough” for me. They meant, “I hope my life lives up to the Notre Dame standard.” That’s what Notre Dame means to them. Maybe it’s my level of familiarity with the University, but I’d never really thought of my life that way. After this trip, I hope that what I do lives up to their standard.

All of these stories will be archived—preserved for future generations and available for the entire Notre Dame family to hear. The Notre Dame Alumni Association has begun podcasting 3- to 5-minute edited clips of those interviews on its oral history website page .

Katie Freddoso, a freelance audio and multimedia producer living in Portland, Maine, is editor and producer of the Notre Dame Oral History Project.

Photo of Katie Freddoso by Matt Cashore