The summer of 2023 was the hottest on record worldwide, in the oceans as well as on land. Waters off the coast of Florida reached the highest sea surface temperature ever measured, 101 degrees Fahrenheit, just right for a hot tub but not for coral reefs, which are bleaching and dying. Warmer waters hold less oxygen, so rafts of fish are suffocating and washing ashore. The added heat encourages algae blooms, which block sunlight from reaching underwater plants and further deplete the oxygen, creating so-called dead zones, a label better suited to a zombie movie than a patch of ocean.

We land animals are also gasping. In July, the National Weather Service issued heat alerts affecting 170 million Americans, half the population. In many parts of the country, laying a hand on the hood of a parked car could raise blisters. To pick one sweltering spot, Phoenix endured 31 consecutive days with highs at or above 110 degrees, a new record for American cities. Saguaro cactuses, those icons of the desert, were collapsing from the combination of heat and drought. Hospitals from Arizona to Florida were treating patients who had suffered burns from falling on pavement, which could reach 180 degrees. Around the planet, countless animals, wild and domesticated, have died from the extreme heat, and so have tens of thousands of human beings who worked or slept outdoors, or who lacked the money for air conditioning.

We broke no temperature records here in southern Indiana, but merely suffered the usual muggy misery we expect in June, July and August. To escape the heat and ease my grief over what we clever primates have done to Earth, I spent the cool morning hours once a week sitting at a picnic table in the shade of a giant tulip tree, along with a dozen or so other volunteers, coaxing native plant seedlings out of the crowded flats where they had germinated in the spring and nestling them into the pots where they would spend the fall and winter. In the spring, with help from many of the same volunteers, the plants will be set out in local wetlands, prairies and forests protected by the Sycamore Land Trust.

The fancy name for what the land trust staff and volunteers are doing is ecological restoration; the informal name is “rewilding.” I like the latter term, because it’s a reminder that we are only assistants to nature in the healing of abused lands and waters. Given the scale of the damage, in my home territory and around the globe, it’s easy to get discouraged. What’s the point of cleaning up a creek, I wonder, in a state with 25,000 miles of rivers too polluted for swimming, fishing or drinking? But nature does not calculate the odds. Nature never quits, not in the backwoods of Indiana, not in the backyard, not in cities where coyotes prowl at night on streets hot enough in the daytime to scorch bare feet, not in box stores where sparrows flit among the ceiling joists while customers fret about rising prices, not in buttoned-up houses where ants scout for bits of food on the kitchen counters and crickets sing in the basement.

To rewild a place is to invite the full energies of nature back in. In our region, if you plant oaks, hickories, maples, beeches and other native trees on land once covered with forest, year by year the forest will return, and with it the spring wildflowers, woodpeckers, warblers, owls, bobcats, foxes, ferns, mushrooms and other woodland creatures. If you dig up buried tiles that drained swamps for farming, rain and snowmelt will gather once more into pools and marshes, attracting frogs and crayfish, muskrats and otters, geese, ducks and sandhill cranes. You might even lure whooping cranes, who have taken a liking to southern Indiana. Put up nesting boxes, and they will soon be claimed by swallows and bluebirds. Shield creeks from eroded soil and toxic runoff with a dense border of plants, and once the water runs clear, beavers will show up to build dams, enlarging the wetlands. If you plant milkweeds, coneflowers, goldenrods, asters, great blue lobelias and other sturdy natives in those restored wetlands, their nectar will draw bees and butterflies and birds.

Nature is resilient, resourceful, relentless. Henry David Thoreau was stating the plain truth when he made his famous claim: “In wildness is the preservation of the world.”

Notice that Thoreau didn’t base his hope on wilderness, which is rare and endangered, but on wildness, which is pervasive and enduring. Wildness is the shaping power of nature manifest in everything, living and nonliving, starfish and stars, soil and sun, winds, waters and whales. Wildness drives the moon in its orbit, the advance and retreat of tides, the emergence of an oak from an acorn, the union of sperm and egg. Wildness is the power at work in every cell of my body as I write these lines, and in every cell of your body as you read them.

Depending on when you read these lines, the cells in my body may have become ash or compost. For wildness preserves the evolving universe in all its diversity and abundance but sustains no piece of it forever, not me or you, not any animal or plant, not even mountains or galaxies. The mountains erode, the galaxies disperse. Everything nature makes it sooner or later unmakes, and then it fashions something new with the salvaged parts. We can’t opt out of this process, but we can choose to join in knitting things together rather than tearing them apart.

Last summer, those of us who sat around picnic tables nestling tiny plants into pots knew we could help mend our local piece of Earth only by aligning ourselves with wildness. The volunteers who showed up most weeks ranged in age from their 20s to their 70s. I was up toward the white-haired end of that spectrum. The youngsters were mainly student interns, their fresh faces a reminder of my days as a teacher, and the oldsters were mainly retirees. Who else could show up for a couple of hours on a weekday morning to play in the dirt? It felt like play to me, gingerly handling seedlings, chatting with other plant-loving people, listening to the chorus of birds. No bird sang for long without someone announcing its name. The chorus thinned out as the morning advanced, and it stopped abruptly whenever a red-shouldered hawk loosed its piercing call overhead. I understood that sudden hush, for the hawk’s first cry raised the hairs on my neck.

Off and on during the summer, the wind brought us the haze and smell of woodsmoke from forests ablaze across Canada. By the end of August, nearly 40 million acres had burned, an area roughly the size of Georgia, far surpassing the toll from any previous fire season in that continent-spanning nation. The carbon once locked up in those hundreds of millions of trees, now released into the atmosphere, will nudge Earth’s temperature higher, increasing the frequency and intensity of wildfires.

On the smoky days, every breath, like the daily news, was a reminder that the web of life on Earth is unraveling. I didn’t need reminding, nor did any of my fellow volunteers, for we all knew about melting glaciers, rising sea levels, vanishing species, declining crop yields, heatwaves, droughts, floods, famine and throngs of climate refugees desperate to find new homes. That knowledge was a key motive for our gathering at those tables, nursing native plants, and it was a dark undercurrent to our chatter about books, birds, family, politics, even our jokes. (“How do you avoid leaving a carbon footprint? Never walk, leave only tire prints.”) The knowledge was easier to bear in company, especially among people determined not merely to lament the devastation but to undo some portion of it, no matter how small.

Aldo Leopold, author of the conservation classic A Sand County Almanac, remarked that “one of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen.” Leopold wrote those lines in the 1940s, the decade of my birth, when the world’s human population was less than one-third of what it is today, and the numbers of Earth’s myriad other species were much greater than they are now. He would have been appalled by the World Wildlife Fund’s 2022 estimate, based on global scientific monitoring, that the populations of vertebrates — mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish — have decreased on average by 69 percent since 1970. Try to grasp that: a decline of more than two-thirds in half a century. Leopold would have been even more disturbed by estimates that the current rate of species extinction is between a hundred and a thousand times higher than the rate prior to the emergence of Homo sapiens.

Some call it ecological restoration. I prefer the term ‘rewilding,’ because it’s a reminder we can only assist nature in healing itself.

These losses should give pause to anyone who regards the Bible as a source of moral guidance. While the Book of Genesis places humans at the top of the living hierarchy, it tells us that plants and animals were created before Adam and Eve. On the third day of Creation,

God said, “Let the earth put forth vegetation: plants yielding seed and fruit trees of every kind on earth that bear fruit with the seed in it.” And it was so. The earth brought forth vegetation: plants yielding seed of every kind and trees of every kind bearing fruit with the seed in it. And God saw that it was good.

Then on the fifth day,

God said, “Let the waters bring forth swarms of living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the dome of the sky.” So God created the great sea monsters and every living creature that moves, of every kind with which the waters swarm and every winged bird of every kind. And God saw that it was good. God blessed them, saying, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the waters in the seas, and let birds multiply on the earth.”

And on the sixth day,

God said, “Let the earth bring forth living creatures of every kind: cattle and creeping things and wild animals of the earth of every kind.” And it was so. God made the wild animals of the earth of every kind and the cattle of every kind and everything that creeps upon the ground of every kind. And God saw that it was good.

The abundance of plants and animals celebrated in these passages is what we call biodiversity. How would the Creator of such abundance judge our voracious, aggressive species, which swells in population and consumption while the numbers of our fellow creatures plummet and whole tribes of plants and animals, with lineages stretching back millions of years, disappear forever? One no longer needs an ecological education to see and feel the wounds — to atmosphere, oceans and lands, and to millions of dwindling species — nor need one bear that awareness alone. Millions now share it. The damage remains invisible only to those who refuse to look.

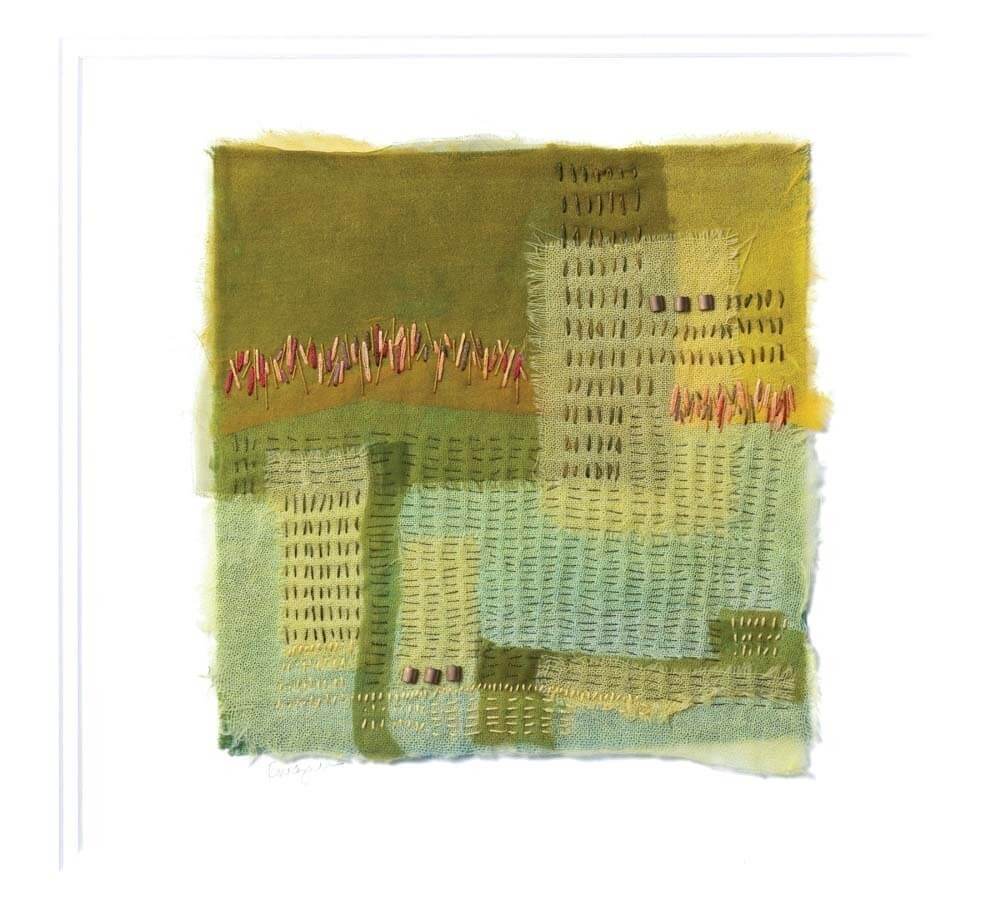

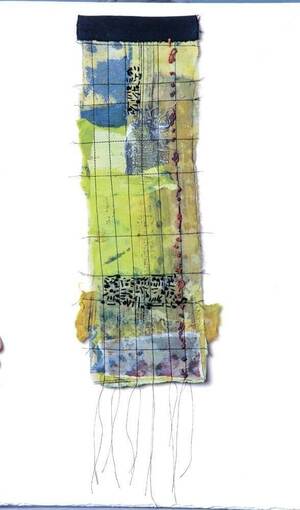

Whether or not my mates at the picnic table had ever consulted the Bible, they all rejoiced in the living Earth and saw that it is good. You could read that affection in their faces, hear it in their voices. One day, as we were potting up a grass called little bluestem, I imagined each slender green leaf was a thread for stitching up a tear in the web of life. As I watched the woman next to me deftly handling those green threads, I remembered watching my mother’s hands when she taught me how to sew. I would have been 11 or 12, preparing to go away for a week at summer camp — 4-H, maybe, or Boy Scouts — and Mother wanted to make sure I could sew on a button or stitch a seam, since I was an outdoor kid, hard on clothes, and she didn’t want me looking like a ragamuffin.

She was a great believer in mending things, and so was my father. They had grown up during the Great Depression and had spent their early married years coping with wartime rationing. “Money doesn’t grow on trees,” Mother would say, when I asked for new jeans so I wouldn’t have to wear my old ones to school with patches on the ripped knees. Her father, an immigrant from Persia, studied hard and became a doctor in Chicago, then went bankrupt during the 1930s because he continued providing care and medicine for his out-of-work patients when they could no longer pay him, until he in turn could no longer pay his own bills. The banks confiscated everything he owned except his clothes and medical instruments. That a person without a cushion of savings could become a pauper overnight was a lesson my mother never forgot.

My father, one of 11 children and the youngest of six boys, grew up on a Mississippi cotton farm. The family always had enough to eat, since they grew their own food, but they had little money to spend at the store. If a part broke on the well pump or tractor, they couldn’t run into town to buy a replacement. Instead, my grandfather fashioned the needed part in his shop, and each of his sons learned how to use the lathe and saws and welding gun. While I was growing up, my father could fix every device we owned, from the car and washing machine to the mower and TV, and he sustained that practice until the introduction of plastic parts and printed circuits, which are designed to be unfixable.

My parents’ frugality arose not only from living through hard times but also from their religious beliefs. If life is a gift from God, then to waste food, electricity, gasoline, wood, wool, soil, water or any of life’s necessities is to be ungrateful. They were fond of citing the Bible’s many cautions against the worship of money and the things money can buy, as when Jesus warns, “Take care! Be on your guard against all kinds of greed, for one’s life does not consist in the abundance of possessions.” When you have more than you need, my parents taught me, don’t hoard it, but share your excess with those who might not have enough.

Their thrift was associated in my mind with their love of plants, which provided us with vegetables from the garden, fruit from the orchard, bouquets of flowers, firewood, shade and homes for hundreds of critters. During the Great Depression, my father planted pines in Mississippi as part of the Civilian Conservation Corps. He planted trees on the Tennessee farm where I spent my first few years, and on the Ohio farm where I spent my school years. My mother planted flowers around every house she lived in — Shasta daisies in Tennessee, lilacs in Ohio, gardenias in Louisiana, irises in Oklahoma, lilies in Ontario, azaleas in Mississippi, gladiolas in Indiana. Violets and begonias bloomed from her windowsills.

How could one be reared by such parents without learning to love plants, those fountains of true wealth?

In his autobiography, the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung described plants as “God’s thoughts.” I prefer to leave the Great Mystery at the heart of things unnamed, and to think of plants as “Earth’s thoughts,” expressions of the creativity at work everywhere on our planet. Whether life has emerged elsewhere in the universe, we don’t yet know. What we do know is that all life on Earth, including ourselves, is interwoven, sustained by plants that capture energy from the sun and enrich the atmosphere with oxygen.

This living web remained largely intact from the time of the most recent mass extinction some 65 million years ago until the advent of the industrial revolution and the surge in human population two centuries ago, when the web began unraveling. Today, under the pressure of our machines and appetites and sheer numbers, ancient species are vanishing, aquifers are drying up, deserts are spreading, pollinators are perishing, fish stocks are dwindling, topsoil is eroding, plastic is smearing the oceans, toxic chemicals and heavy metals are contaminating mother’s milk, on and on. A full inventory of the havoc would fill a book.

No amount of human effort can undo all the damage. We can’t mend every broken strand in the web of life. But we can mend some. We can stitch up tears in our local lands and waters, in our neighborhoods and communities, trusting that people elsewhere, everywhere, will do the same in their own home regions.

If the task seems daunting, imagine you are crossing a desert on foot. The sun beats down from a cloudless sky. There is no road to follow, no clear path. Wherever you look, bare sand stretches away to the horizon. Weary, discouraged, you’re tempted to stop, to lie down in the scant shade of a dune and sleep. But giving up means abandoning the people you love, the places and creatures and beauties you cherish. You think of seeds putting down roots and sending up shoots. You think of sea turtles swimming across oceans to lay eggs on the beaches where they were born, arctic terns flying from pole to pole, monarch butterflies dancing their way south from the Great Lakes to winter refuge in the mountains of Mexico, all the undaunted creatures intent on their journeys; you think of children and the young of every species, all burning with the urge to live. So you keep walking.

Then, far in the distance, you see a speck of green. It must be a mirage, you think, an illusion brought on by your need for hope. But as you trudge forward, the speck enlarges, turns a deeper green and takes on the shape of trees.

If this were a real desert, the trees might be date palms, apricots or figs. But since you are imagining the scene, let them be your own favorite trees — maples, perhaps, or cedars, birches, sycamores, hickories, pines. Whatever the species, that green canopy means water, fertility and life. It also means that people have been at work here, since most of what grows around a desert spring has been planted and tended by humans, often for hundreds of years, generation after generation.

On reaching the oasis, you discover people are gathered here now, all ages and complexions, playing, napping, hugging, sharing a meal, nursing a baby, swapping stories, singing. As you enter the shade, voices call out welcome in several languages. Someone gives you a mug. You dip it in the pool at the heart of the oasis and drink until your thirst is quenched. Now you feel the weight of travel in your legs. Seeking a place to sit, you notice a table where half a dozen people, chatting and laughing, are nestling tiny plants into pots. A woman with white hair in a ponytail holds a seedling in one hand, and with the other hand she beckons you, patting an open space beside her on the bench. So you take a seat, roll up your sleeves, and set to work.

Scott Russell Sanders is a distinguished professor emeritus of English at Indiana University and the author of more than 20 books of fiction and nonfiction, most recently Small Marvels: Stories.