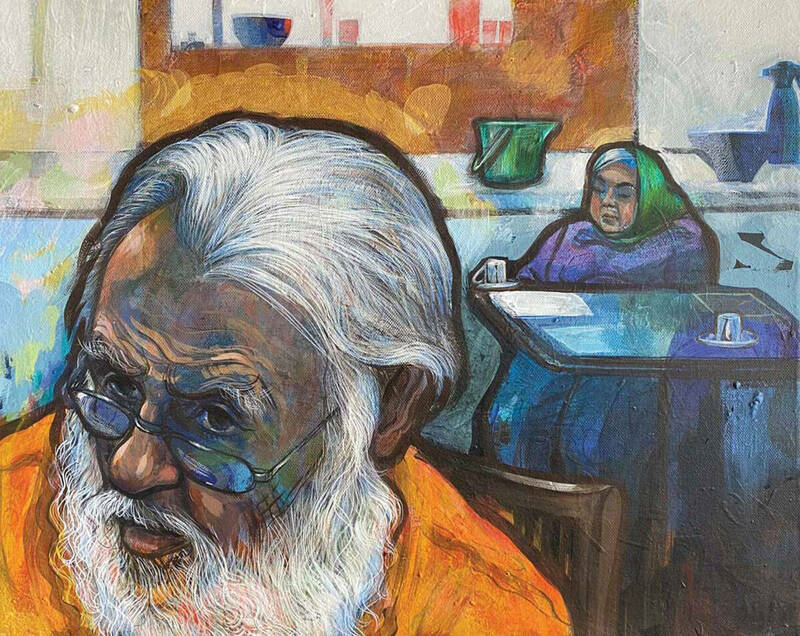

Illustrations by Birdie Thaler

Illustrations by Birdie Thaler

Raphael Morton Thaler was Roy to everyone who knew him, Raphael lately to his caregivers and RM on the dotted line. He always said he didn’t care what people called him. “Call me anything but late for dinner!”

Late Sunday night Roy, Dad, Grandpa Roy, Grumpy Roy, Raphael, et cetera ventured further out into the fog of dementia, fell asleep and did not wake up.

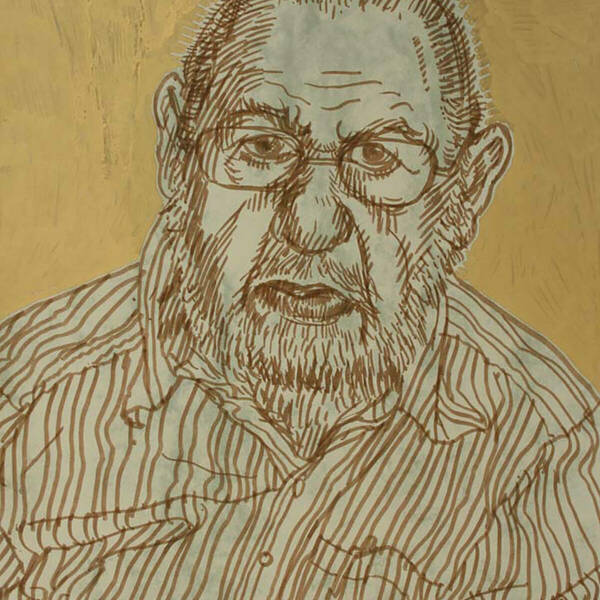

He was a big, warm-hearted, joyous man with a deep laugh and a bushy beard, which he’d had since 1970, except for a few days this year, after one of his caregivers was washing him and asked if he wanted his beard shaved. He answered, “Yes,” which in my interpretation meant, “Yes, keep touching me, keep taking care of me with your gentle, warm hands.” The beard grew right back.

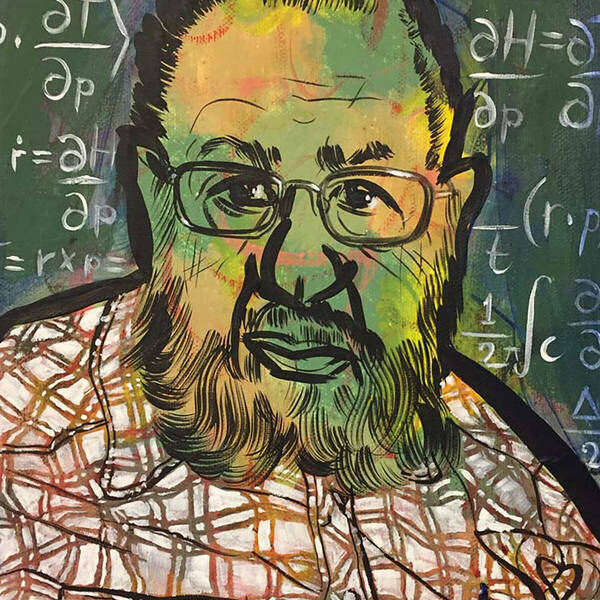

He was a theoretical physicist and worked in quantum mechanics, which is Greek to me.

Years ago I asked our mother if she had any idea what Dad actually did all day every day, scribbling his mathematical formulas on yellow legal pads and talking for hours on end with his physicist friends on the kitchen phone; she admitted that no, she didn’t know, but she knew he couldn’t find the eggs in the refrigerator.

So, he was brilliant, but also old school in the way that boys had of going from being taken care of by their mothers to being taken care of by their wives as they turned into men, and then later, as they grew old, by various other women whose job it was to take care of them.

He was a kind and gentle father, at least by the time he got down to my brother Willie and me and had already been nicely worn in by our two older brothers. When he got angry, he’d thunder, “I’ll take my strap to you!” but to us he never did.

Once when we were quite small, Willie and I were in the backyard with him, and he got so angry that he actually did take off his belt. We were not afraid of him in the slightest, especially because we knew that without his belt, his pants were so baggy that they’d fall down if he tried to catch us. He stood there looking foolish and rotund, holding his belt like a dangling snake from one hand and the bunched-up waistband of his pants in the other as we ran round and round him in circles, laughing and yelling, “No, you won’t!” until he finally started laughing, too.

This remained my strategy throughout my life for dealing with his impatience and grumpiness: I would badger and poke and tease him until he’d forget why he was irritated and we’d both laugh.

Roy never lost his sense of humor or his kindness, but it was a still a surprise to me how, toward the end, when there was so little of him left, new aides and caregivers who’d just met him would say the same things about him: “He’s so funny, always joking. He’s good-hearted.” He was who he was, until the end.

He loved singing in his tuneless baritone and would happily bellow out his favorite songs from World War I and World War II, from Gilbert and Sullivan, Cole Porter, the Gershwins, or Flanders and Swann. When he could no longer hold a real conversation, we’d just sing to each other (a bit embarrassing to me, as I was always aware that the aide holding the cellphone for him had to listen to us). I’d sing the first few bars of an old song: “Daisy, Daisy . . .” and point to him on the screen, and he’d sing the next: “Give me your answer true.”

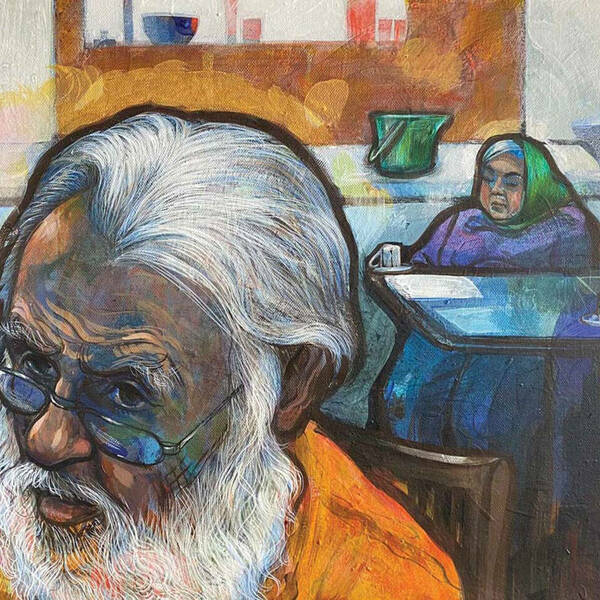

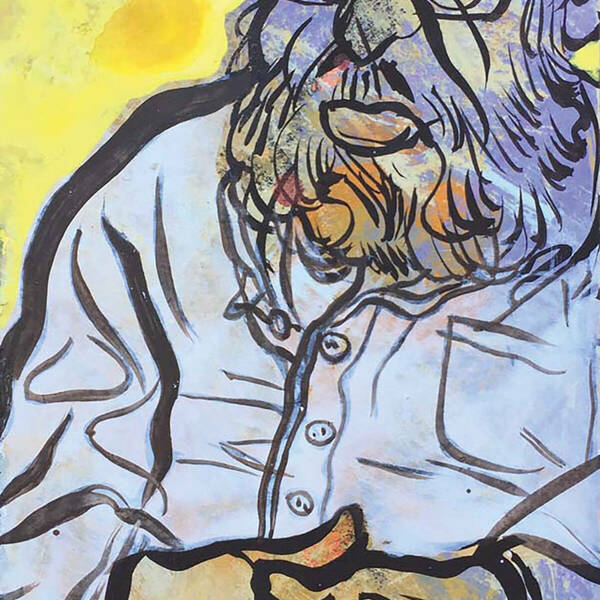

All my life I have done drawings of my father, but once Alzheimer’s got its claws into him, sitting silently together for hours while I’d paint and draw him became our way of being together without the pressure of having to talk. I’d hold up the drawing to show him, and he’d always say, “Who is that ugly old man?”

I’d chuckle at this quintessential Dad response, but he was so adept at using wisecracks to sidestep the holes in his memory that I was never sure whether he recognized himself or not.

For years now, painting portraits of my father has been part of a long process of mourning him before the fact. That is, mourning the father I used to be able to talk to about almost anything, who was always informed and always had an opinion and was always willing to argue and usually to learn.

To some extent I started missing him long ago, when my mother died and part of him broke. I think he lost that piece, even if he (and we) still had many good years ahead. But something small but essential was gone, the banter had lost its depth.

Roy was, for all his education and extreme intellect, a simple person: warm, generous, impatient and stridently anti-fashion (as was the fashion of theoretical physicists back then).

He was completely unimpressed by titles or degrees or pedigrees of any kind and only interested in how people (and some dogs) behaved and what they had to say. He loved people, especially “regular” ones in regular jobs whom he could engage in interesting conversation.

He was always cheap about small things — “I’d never pay more than $20 for a pair of shoes!” (or was it $10?) — but generous with anyone he knew who needed a hand. Sometimes it was obvious that the person was taking advantage of him, and I’d get exasperated and chide him for letting them make a fool of him. He did not care and would say: “Better to risk being made a fool of than miss an opportunity to help someone.”

He was an expert practitioner of the Jewish three-beat aphorism. At age 19, long before the internet or cellphones or affordable international phone calls, I was about to leave for Japan, alone, for almost a year. I was getting nervous about the trip, but he waved off my worries dismissively: “You’ll pack, you’ll go, you’ll be fine.”

In his last years Dad spent many hours sitting in his giant armchair, looking out the window, watching the birds. He had accumulated an impressive panoply of life-threatening diseases, which, to the mystification of his doctors, he was managing to survive; his world had become smaller and smaller, but he was, as he put it, “still toodling along.”

I would call to check on him, and he’d cheer me up. I’d ask him how he was. “Couldn’t be better!” he’d say — and mean it.

He was an expert in concepts I am incapable of imagining, like the quantum theory of scattering (?), infinite limits (??) and nothingness, in which he was a firm believer. He was an atheist, yes, but most of all, an optimist. “When I’m gone, I’m gone,” he’d say, with a blithe shrug.

To sum up, if I can sum up such a larger-than-life man, he loved talking with people and singing and slightly grotesque wood sculptures and bad puns — real eye-rollers, now called “Dad jokes” — like his classic: “Noses run in our family.” He loved birds and big hats and meat and potatoes — “I’m big on meat and potatoes!” was another classic, which invariably led one of us to poke him in his ample belly and snicker. He was also ticklish and would close one eye and shake his shoulders up and down with a low “Heh-heh-heh-heh-HEH!”

He loved coffee cups with handles large enough for his big, beautiful, soft hands, and he truly loved pastry and all things dessert-related. At his assisted living, then enhanced assisted living, then nursing home, he always ordered dessert “à la mode” which, if you happen to be a French person reading this curious American fancifying misuse of French, just means “with ice cream.” So, twice a day, he’d manage to order two desserts: “cheesecake à la mode,” which equals cheesecake plus ice cream. With his pastries he loved hot coffee and flirting with waitresses. (Sorry — I know it’s a #MeToo no-no, but it’s the truth: Roy would ask for a smile from the server as she leaned on one hip, holding her Pyrex pitcher of coffee, and he’d get one, a real one, because he was warm and kind and respectful and left big tips.)

If you want to pay homage to dear old Roy, you can follow his advice (risk being made a fool of rather than miss a chance to help someone) or just eat (preferably pastries, not just one but two), drink (preferably coffee, black and hot) and be merry.

Raised in Cleveland, Birdie Thaler is an artist living in Malmö, Sweden. See more of her artwork at her website, birdiethaler.com, and on Instagram @birdiethaler.