Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt from Every Play Every Day: My life as a Notre Dame walk-on.

When I was growing up, going to a Notre Dame football game was an annual pilgrimage, like going to Mecca or Lourdes or Jerusalem. When I attended my first Notre Dame game, I experienced something visceral. I felt an esoteric camaraderie and the feeling was not something I could package together and bring home to show my friends. It was something that transcended the present moment, and I could feel it, even though I could not see it. For brief moments on those fall afternoons I was part of the tradition, a part of the history. It took only one of these awe-inspiring trips to campus for me to know Notre Dame would always be a part of me—and would be the place I would play football one day.

The magic begins long before kickoff. My first Notre Dame game was the 1987 Notre Dame versus Michigan State game, which is still one of only a handful of night games ever played in Notre Dame Stadium. My dad took me to the game, but before taking me, he faced a moral dilemma. He had tickets to see the Pope in Detroit, but he also had tickets to the Notre Dame game. In the end, he took me to the Notre Dame game because he thought it would be more of a religious experience for me! It’s a wonder we weren’t struck by lightening in the car ride to South Bend, Indiana.

The night before every home football game there is a pep rally. My dad took me to this standing-room-only event the night before Notre Dame played Michigan State. The pep rally begins at 7:00 p.m. and includes performances by the band, the cheerleaders, and the dance team. After the performances there is usually a celebrity speaker, followed by speeches from two football players, and then, lastly, the head coach addresses the congregation. For a 7-year-old, the site of one hundred Notre Dame football players dressed in suits being supported by twelve thousand loyal fans left a lasting impression.

After the pep rally we walked over to the stadium and witnessed another Friday night ritual. Before every game, home and away, the football managers paint each player’s helmet gold, using paint containing real gold dust. Hundreds of spectators gather behind the gates at the north side of the stadium to witness a tradition that has been in place since the mid-1960s. Perhaps it was the paint fumes I inhaled standing behind the gates watching the helmets glisten, but I had no doubt, even at age seven, someday the managers would be painting a helmet belonging to me.

The next morning my dad woke me up early so we could take in the sights and sounds of the campus on game day. The campus usually comes alive at 7:00 a.m. when the students wake up to begin the day’s festivities. But since this was a night game the students slept in on this particular Saturday. Still, throughout the day the campus was besieged with fans of all kinds, from the little girl in pig tails wearing the Notre Dame cheerleading uniform, to the 1932 graduate who looks like he dressed in the dark wearing his collage of Notre Dame colors as a visual reminder of his heart’s allegiance. Notre Dame’s campus landmarks become a pilgrimage for some on game day. The Grotto, the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, the Golden Dome, and the Hesburgh Library, with its famous façade colloquially known as Touchdown Jesus, receive thousands of visitors on these fall afternoons.

But our destination that day was Bond Hall, the architecture building where the band congregates before raising their cacophony of sound throughout their marching tour of campus. I watched and listened as the brainwashing continued. This time the vehicle of manipulation came in the form of music. Once I heard the fight song (whose words I already memorized), I was forever hooked on the Notre Dame mystique. I began to get goose bumps. From the steps of Bond Hall we followed the band on their march to the stadium. In their wake they left a line of people four or five deep on either side of the walkway. Upon reaching the stadium the band filed in through the main gate, and my dad and I made our way to our seats.

Chants of “LET’S GO IRISH!” greeted us as we navigated to our seats. At the time of my maiden voyage into Notre Dame Stadium, it only seated fifty-nine thousand. The stadium has since been renovated and now houses over eighty thousand. In this intimate stadium environment the “LET’S GO IRISH!” chant reached a crescendo by the time we found our seats on the forty-yard line, four rows from the top of the stadium. My dad and I secured a perfect vantage point for the events about to transpire.

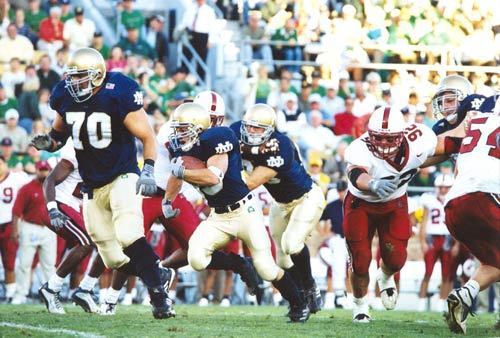

A hush filled the stadium as the Notre Dame team began to form a bottleneck in the tunnel at the north end of the stadium. First, I could see only one gold helmet, then two, and then a dozen, then the entire team was bouncing together in a mass of excited energy. To me, they were gladiators, invincible machines ready to annihilate anything in their path. By this time I had joined in the chorus of another chant, “HERE COME THE IRISH! HERE COME THE IRISH!” As if beckoning to the call of the stadium, Notre Dame’s head coach, Lou Holtz, gave the signal to move and the team charged out of the tunnel and onto the freshly manicured field.

The game offered everything I could have dreamed and exceeded every expectation a bright-eyed seven-year-old could have. Notre Dame had a senior speedster out of Dallas, Texas, who many considered to be the best player in the country. His name was Tim Brown and he played flanker, was used as a running back in certain formations, and was also a dynamic kickoff and punt returner. On that crisp September night in 1987, I watched Tim Brown stake his claim on the most coveted award in college football—the Heisman Trophy. On that night, against a Michigan State team who would eventually be crowned Big Ten and Rose Bowl champions, he had back-to-back punt returns for touchdowns. His runs of sixty-six and seventy-one yards solidified his position among college football’s best players. At the end of the season, Tim Brown became Notre Dame’s seventh Heisman Trophy winner, due in large part to his performance against Michigan State. The excitement in the stadium was electric, and I knew I wanted to be a part of the emotion one day.

After my initial foray into the Notre Dame experience, I went home and wrote a letter to my new hero. It read, errors and all,

Dear Timmy Brown,

Yesterday my daddy took me to the Notre Dame vs. Michigan State game. I saw you run back too touchdowns. I’m seven years old and I like football and I think you are grate. I would be so happy if you would sign your name on this paper and send it back to me to show my friends.

Your friend,

Timmy O’Neill

Six months later I received a letter postmarked from Dallas, Texas, Tim Brown’s hometown. He had signed it, “Best Wishes, Tim Brown #81.” I was awed. Tim Brown had taken the time to respond to my letter. It was a feeling I would remember fifteen years later when I found myself on the receiving end of a similar letter.

Timmy O’Neill is a fourth generation Domer who studied finance and theology. He currently is a natural gas trader for Sequent Energy in Houston, Texas. He lives with his wife and two daughters in Katy, Texas. Visit his website, www.everyplayeveryday.com.