For the most part we sail our own ships in life on a vast ocean of opportunity, chance and expectation. Time is short but we are not rushed. However sure we are at first of our direction, the wind can shift. Our adventures are bound to reveal secrets, bend aspirations and expose us to new ways of thinking. The compass swings round, sails fill and eventually new horizons appear. Magic really, or better, grace. For life is an unwarranted gift.

We begin with the hand we are dealt, I suppose. Mine was odd. After my carefree childhood in agricultural California, my mother remarried and abruptly we moved to Manhattan. Suddenly I was submerged in Latin, language and literature via the Jesuits. A quantum leap from public school. At 14, my heroes were artists and writers, people like J.D. Salinger and E.E. Cummings, Frost, Fitzgerald, Steinbeck and Bob Dylan.

This didn’t mean we wouldn’t slip off on a Friday afternoon to Yankee Stadium to see Roger Maris swat the ball out of the park, ever sympathetic to those left behind to weather the Library Science class. But with baseball, at best, all most of us can do is watch. The imaginary world of literature, however, seemed like an old lawn chair by a lake just waiting for me to sit down. What did Holden Caulfield really want? Were all the great writers drunks? How dare Cummings use only the lower case. Who was Baby Blue? The idea that one of us might someday pen the great American novel went without saying.

Summers were spent surfing at the Jersey Shore and building things in our garage. I built a skiff to pilot on Barnegat Bay, all pumped up over my woodworking skills, and rehabilitated a 1951 Cadillac Allard (an awesome vehicle). This early fascination with mechanics would prove integral. One summer my brother and I jumped in a camper and drove 10,000 miles, all over the country, a copy of Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley on the dashboard. We camped and read and explored. Head and hands, that’s how I’m wired.

The most fun

Landing at Notre Dame in 1965, I was anxious to slip the Jesuit noose and vaguely interested in an English major. An immediate sense of family, the beauty and excitement of campus and dozens of brand new pals spun me in a happy loop. I felt on the verge of something. I’d learned a little bass guitar as a kid and soon enough was in a campus rock band, one of the most fun things anyone can do.

Ahh, “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” rolling through the crisp fall air from the porch of Sorin, game day morning. Saint Mary’s girls smiling. One band turned into another and suddenly Spanish II took a back seat to working the dance halls and clubs around Michiana and elsewhere. Oh, we played the hot spots: Akron, Kalamazoo and Valparaiso. Setting the bar a bit higher, we four Domers moved to Los Angeles in 1970.

A minor record deal, writing, touring and recording — those four years with Captain Electric and the Flying Lapels were an unforgettable experience.

We didn’t witness the ’60s, we lived them. I’m proud of the progress we made down a hard road and grateful for God giving us a shot at the big time. Some chances come but once. Playing music has remained a faithful sidekick even today, some 40 years on.

Back at headquarters, in the fall of 1972, Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, was changing sails. He gave a big fried chicken soiree on the South Quad to welcome the new female (!) students. I don’t know what he said because . . . I was distracted.

A new major appeared that year, American Studies — history, government and literature. I took the opportunity to immerse myself in classic American novels, Upton Sinclair, Frank Norris, William Faulkner, the works of Flannery O’Connor and William Saroyan. I sat in the library and read for two-and-a-half years. It was an in-depth study of the great American landscape, mental, physical and spiritual.

The grandeur of our bountiful homeland has been a prime source for literature but also, I believe, a wellspring of hope. Formal histories are typically written by the winners, but I’ve filled in the gaps to include the story of the real first settlers, men and women bravely crossing a land bridge to Alaska 10,000 years ago. I have made it my business to learn of Indians, simple farmers, miners and frontiersmen from whom our character emerges, and I find their stories far more intriguing than any of generals or politicians.

What’s unquestionable is the magnificence of the land, and I hope a better sense of our custodial duties becomes apparent, ensuring that the wellspring is available to future Americans. For me, a sense of place is my spiritual anchor. When I read Huck Finn I am right on that raft. Traveling through the Nebraska plains, I am Meriwether Lewis. At sea, we are all Ahab. We are all on the boat.

New ways

After graduation I tried the business world in New York City. In business, I found, you must sometimes stand behind things you do not believe in and that I could not abide. Restlessness and the drab mood of the city were telling me an entirely different path was needed.

During the spring of 1977 my fiancée and I spent a weekend on Block Island, a few square miles of old farmland 16 miles out to sea, south of little Rhode Island. We were instantly taken with the quiet, the remote beauty, the simple people and the gray windy Atlantic in March. It was another quantum leap. We planned to spend a year but that turned into seven. “Life’s what happens while you’re making other plans,” they say. The real trick is to bring the two together.

The island was settled by English farmers in 1666. Rolling hills and fields neatly boxed out in stone walls, high above the ocean: It offered clean air, few people, straightforward work and an altogether new lifestyle, lives led more by circumstance than agenda. A nose for the wind and ready advice from neighbors. The safety of a community well aware of its limitations. A warm stove in winter, an exhilarating sail in summer. In the words of John Fowles:

True islands play the siren’s (and bookmaker’s) trick: they lure by challenging, by daring. Somewhere on them one will become Crusoe again, one will discover something: the iron-bound chest, the jackpot, the outside chance.

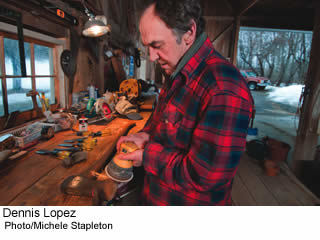

I found work as house carpenter and, in the words of an 1892 tradesman, “endeavored to do honest and careful work and thus merit a share of public patronage.” It wasn’t until I joined a crew that I learned framing. In two years I had designed and built our own place. What a sense of satisfaction. Variations on the Cape Cod design would more or less become a mantra for my working life. It’s a good box to be in. Passing old work sites I hear the laughter of the workmen long after it’s over. I still do it today.

Carpentry teaches patience and diligence. Speedy work is rarely fine work (except on TV, where folks with brand new tool belts install French doors in 10 minutes). Our culture is fraught with sales pitches and white noise, wed as we are to consumerism, speed and convenience. But a fruitful life may demand more. Call me a traditionalist. I like the nails loose in bins, not wrapped in tiny plastic packages. Taking the time to pick out lumber is a pleasure. I have 22 years on the current hammer and can’t sleep if I don’t know exactly where it is.

The handsomest house I ever saw is called Fiddler’s Green. It is a simple cape cluster, perfectly proportioned and finely crafted, with few modern systems. The home was sketched out on a paper bag and built by a seasoned island carpenter. Oddly, none of its dimensions are divisible by four. He worked from an intuitive knowledge of the form diluted through years of experience. He worked without haste, great cost or ambitious expectation. This skill cannot be faked, bought or sold.

We learned much from the islanders. Self-sufficiency and independence. They are hard on the exterior but soft inside and good in a crisis. There is mirth on islands and life is always intriguing. No need to lock your door. Knowing my neighbors and upholding my end of an unspoken understanding — do right by another and he’ll do right by you — has kept me happy, humble and safe. Living with these circumstances — relative isolation, solid community and challenging weather — cultural veneers are stripped away. What’s important in life becomes eminently clear.

Later I lived on two other islands, totaling 27 years offshore. Resort places quiet in winter, humming come summer. My unconventional career has allowed ample time for travel, music and writing. A lengthy tour of Iceland gave me an inkling of what island culture on a grander scale might look like. In Egypt I got to see the most magnificent structures ever put up by man, spiritual expressions of a culture that lasted 3,000 years and one we are yet to fully understand. Winter trips to California and Mexico for some extra sunshine break up the working year. We vacation to better appreciate what we have at home, to widen the lens and begin again fresh.

Another day

No life is perfect, and I’ve certainly experienced downtimes. Years ago there came a day when I had to admit a drinking problem and be willing to act. Again, strangers showed me the way. That was the best change I ever made. A family member has bravely battled long-term illness, and we never knew what was next, but she’s fine today. Hardest was the loss of my wife just after coming to Maine. She was taken suddenly in an accident, gone in a day. Words cannot capture those feelings, but God has helped me, speaking and acting through others, steeling me to accept the unacceptable. He held the ship’s wheel when I could not.

There are no cheap seats in life, it’s pay as you go. We get what we’re given, mold it to what we need and move along, often like weary travelers. And there is sacrifice. I have never made a lot of money, but I am satisfied, comfortable and content. The life I have lived is one I’m deeply grateful for. I have everything I ever wanted.

These days home is the Maine coast. Maine’s good for the soul and has a familiar feel to it. People know each other and laugh off what can’t be fixed. The weather is strong and requires determination and perseverance. Magnificent forests stretch to Canada, and my old friend the ocean is nearby.

My sheltie dog and I are off for an evening walk. Peak colors blast the hillsides. On our return the Milky Way will span the heavens above us and the Big Dipper will settle down over my barn. Just as I’m going to sleep, off in the woods a great horned owl will summon us to dreamland. Tomorrow comes another day.

Dennis Lopez can be reached at beachglas@myfairpoint.net. His new book of poems and stories, Freight Train to Avalon, is available on request.