Imagine traveling to the vibrant port city of Alexandria, Egypt, in the year 1000. Perhaps you are a Muslim legal scholar making the pilgrimage to Mecca, or a Jewish physician serving in a royal court, or a Latin Christian merchant trading spices from Indonesia. If arriving by sea, you would sail into the city’s double harbor guided by the Pharos, a towering lighthouse built on an island. Historians believe it was the tallest structure in the ancient and medieval worlds, a marvel to behold. Over a millennium after the Greeks built it, the Pharos still stood, weathering the epochal changes of history.

As a visitor, you would observe the layers of that history reflected in the city’s architecture, economic activity and urban planning. Once the gateway to ancient Egypt, Alexandria had passed in the sixth century from Roman imperial rule to the Arab caliphate. Strategically situated along the Mediterranean coast, it flourished as a commercial hub linking the African and Eurasian continents. All three Peoples of the Book dwelt side by side in this center for philosophical, scientific and theological learning. Ornate mosques, churches and synagogues lined the city’s broad street grid.

Cities like Alexandria illustrate historian R.I. Moore’s dictum, “History begins with cities because cities change, and indeed create, their worlds.” Alexandria arose along a major waterway, the River Nile, where the population could easily source grain, gold and slaves from the surrounding regions. People who had previously lived off the land migrated to the city and organized themselves by trade and craft, creating social hierarchies governed by the wealthy and powerful, who often claimed religious authority. Yet even as the city grew, it remained vulnerable to famine, disease, natural catastrophes such as the earthquakes that eventually felled the Pharos, and the ravages of war.

What was true of urban environments and economies in the year 1000 remains familiar to us today. Moore argues that the city-based civilizations we inhabit emerged between 500 and 1500, the period we call the Middle Ages. Agricultural and commercial production intensified as cities spread, launching an urban revolution that would define this epoch of world history.

The Middle Ages matter because the structures of our modern world — including hospitals, representative assemblies and universities — took shape during this millennium. This is the pitch I made to my students at John Adams High School in South Bend this past spring. As the inaugural public humanities fellow at Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute, a position created in honor of the institute’s 75th anniversary, I taught a special elective course that introduced high schoolers to the interdisciplinary field of medieval studies.

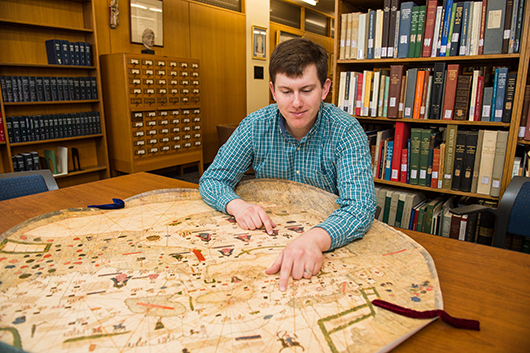

We spent the first week of class looking at medieval maps. The students were surprised to see how many cities then dotted the Eurasian and North African landmass. Yet the maps look strange to modern eyes. For one thing, they were made by Islamic and Jewish cartographers who didn’t know the Americas existed. For another, the region most of us associate with the Middle Ages — Western Europe — appears peripheral. These maps instead center Mecca and the Mediterranean, where the mighty Byzantine and Islamic empires met.

For young people disillusioned with the present state of global affairs, studying this history can be galvanizing.

It’s that shift of perspective that makes the medieval relevant today. Studying the Middle Ages defamiliarizes things my students had taken for granted about the world as we know it — a world constituted by global use of the English language, geopolitical systems that privilege the nation-state, and the pervasive influence of Western civilization. These powerful forces may shape our world now, but they haven’t always. Human societies preceded their development and therefore could, in the future, flourish without them. For young people disillusioned with the present state of global affairs, studying this history can be galvanizing.

My students encountered a transcontinental medieval world connected by trade routes stretching from Ireland to the Indus, from Scandinavia to Sri Lanka. They learned about the cultural heritage of regions they might not have recognized as vibrant intellectual or commercial centers. For example, eighth-century Baghdad under the Abbasid caliphate birthed the Greco-Arabic translation movement, an enormous intellectual achievement that brought nearly all of ancient Greek philosophical and scientific writing into Arabic. Four centuries later, these Arabic sources would, in turn, be translated into Latin for use by scholars like St. Thomas Aquinas.

Modern Baghdad illustrates the danger of neglecting this legacy. Much medieval cultural heritage has been destroyed in recent decades during the “global war on terror,” never to be recovered. It is imperative that we teach our students to care about its preservation. As fledgling American citizens who bear responsibility for the wars waged in their name, high school and college students need to be aware of what is lost when thousand-year-old infrastructure, museum collections and library holdings become collateral damage. Not to mention the loss of cultural memory when entire generations of people are massacred or displaced. What we learn to care about, we will choose to save.

Knowledge of the deep past fosters the practical wisdom that young people need to thrive in our complex world. That belief animated Rev. Gerald Phelan, a Thomist and friend of the philosopher Jacques Maritain, and the founding director of the Medieval Institute in 1946.

From its outset, the Medieval Institute aimed to bring together scholars from different disciplines to train the next generation while cultivating a concern for “the problems of present-day living.” Phelan likely had in mind the need to rebuild after the destruction wreaked by the Second World War. His vision, however, was limited in that he understood medieval cultural heritage to be synonymous with Christianity and western civilization. He wrote, “We Americans belong to that civilization. It is the inheritance which our forefathers brought with them from their European homelands.” Phelan hoped medievalists would shore up that cultural legacy “against false and subtle ideologies, foreign and hostile to its very spirit” — presumably Communism but possibly also secularization.

Today, those of us who teach in medieval studies are reckoning with new geopolitical contexts and the ugly reality that Europe in the Middle Ages is too often represented in Western popular culture as a homogeneously white, Christian space. To the contrary, emerging research in bioarcheology is demonstrating that people from around the world lived and died in medieval Europe. For example, human remains from the plague of 1348-50 attest to the burial in London of people from Africa and South Asia. Such a discovery points to a surprising interconnectivity within the medieval world. We anticipate more findings that witness to the movement of peoples and their cross-cultural encounters as medievalists broaden their archives and radically deepen their understanding of the period. These stories from the past will give us perspective on the challenges of migration, interculturality and global citizenship as we look to the future.

The paradigm shift toward conceiving of a “Global Middle Ages” seeks to lift up the cultural production of marginalized peoples. Efforts by scholars such as Geraldine Heng and members of the Medievalists of Color collective affirm that studying the millennium between 500 and 1500 remains important and can contribute to the contemporary work of anti-racism and social justice.

Turning to the Global Middle Ages opens avenues for scholarship that engages “problems of present-day living.” The myriad challenges of urbanization besetting us today were already emergent in medieval cities. We are still trying to figure out how people of different religions and cultures can live together without racializing and exploiting the labor of others. We are still struggling to survive in a world plagued by pandemic and climate change. We too must devise means of feeding populations who no longer live off the produce of their own land.

Medieval agricultural and commercial revolutions created this world. To envision solutions to these problems, we need to understand how they developed. We might also gain practical wisdom from medieval forms of association, like craft guilds, and social provision, like hospitals. Encountering what remains of the distant past is often a strange and defamiliarizing experience. Yet it might awaken in us dreams for a more flourishing future.

My course at Adams reflects these shifts in the field and the particular strengths of Medieval Institute faculty. Together we introduced the students to a dynamic period of world history. Students reported their surprise to learn about the importance of medieval Islam to architecture, technology and philosophy; advances in shipbuilding and navigation; widening access to education; women’s social power and artistic achievement; and the plurality of cultures that mutually influenced one another. As the lead instructor, I was delighted when a student told me, “I did not expect to enjoy the class, but I thoroughly have.”

Learning about the Middle Ages requires that we face its legacy of violence and conflict as things to be remembered and not repeated. Yet the period also offers histories yet-to-be-told and examples of resilience that reassure us: The world has not always been the way it is today, which means it can change. Systems can be remade. That hope is why the Middle Ages matter today.

Sister Annie Killian, O.P., holds a doctorate in English literature from Yale University and is the public humanities postdoctoral fellow at Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute.