Doug Marsh ’82 is the one person having the most impact on the face of Notre Dame that you may have never heard of.

This warm summer afternoon he is wearing a white safety helmet and a lime-green vest over his starched business shirt and tie, and leading me down that fabled stairway from the football locker room toward the tunnel to the stadium’s field. Anyone who went to Notre Dame knows what sign is there above Marsh’s head: Play Like A Champion Today.

“This stairway is not being touched,” Marsh says. He points up: “We didn’t even repaint this.”

Tradition dies hard on this campus, so no one was going to add even a fresh coat of golden paint to the sign that up close only barely betrays the hundreds of players’ hands that have slapped it on game day over the years.

Photography by Matt Cashore '94

Photography by Matt Cashore '94

But it’s also safe to say that venerable sign is one of the few things left untouched these days at Notre Dame. New buildings are sprouting nearly everywhere on campus. Roads have been rerouted. Underground energy piping is being buried. New sidewalks are connecting it all. For the past three years, dozens of roaring, yellow earth movers, their beeps echoing with every shift to reverse, have transformed the very topography of campus. Thousands of construction workers, some from as far away as Detroit and St. Louis, clad in those same lime green vests and eager to earn union rates, have poured concrete, wired electrical and Internet lines, installed new stadium seats and carved classrooms from cavernous spaces. In just the three new buildings around the stadium, they have laid more than 1,650,000 bricks.

And overseeing all this has been Marsh, Notre Dame’s vice president for facilities design and operations, and University architect. These days, he is a busy man. The thing to remember, he tells me, is “Notre Dame has always been growing. We’re always building Notre Dame.” Marsh is as passionate about the campus he loves as he is devoted to the construction schedules and budgets he must keep in line. You can’t help but get caught up in Marsh’s enthusiasm as he shows off the behind-the-scenes infrastructure, including massive steel support beams that stretched across two lanes of the toll road when they were trucked in from Pennsylvania.

Still, today it’s another architect who comes to mind when taking in the vast changes on campus: Daniel Burnham. More than a century ago, that Chicagoan famously said, “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood.”

Notre Dame’s big plans have led to the current building boom, the biggest in its 175-year history. By decade’s end, 20 new buildings totaling 2,487,715 square feet with a cost of $1.1 billion will have been completed. That doesn’t include renovations, like the $47 million worth of work now going on at the Hesburgh Library to refit it for the digital age.

This past summer so much construction was under way that it was easy for an alum who has not been on campus in the past two years to get turned around. (As is usually true when feeling disoriented in life, it helps to look up to Our Lady on the Golden Dome for direction.)

With the flurry of construction, much of the focus has been on bricks and mortar and expensive football seats and the new stadium video screen. The new buildings around the stadium are awesome. Two are nine stories high. The academic departments started moving in this fall — and that effort will be spread over more than an academic year and require 200 truckloads of furniture to complete. The complex is capturing so much attention that you might forget the other 17 new buildings going up this decade. Most were designed to be certified for environmental sustainability. Two of them line Notre Dame Avenue, and just beyond the DeBartolo Performing Arts Center will be a rarity: an architecture building inspired by classical style — the only new construction not in Collegiate Gothic.

It’s easy to forget that all this construction — from new residence halls to the Compton Family Ice Arena to the Eck Hall of Law to the new student center, complete with a three-story rock-climbing wall and an enormous career center — are just the physical manifestation of the University’s ambitions for itself. Make no mistake, Notre Dame has entered a new epoch in its storied history.

And, as Burnham said, big plans can cause blood to stir.

“I’ve only been here six years and I wouldn’t recognize the place,” says Margot Fassler. We’re having lunch at Rohr’s at the Morris Inn, which also has undergone a $30 million renovation this decade. It was the quiet week on campus, after graduation and reunion and before the summer sessions and sports camps that pack the place. Yet Rohr’s was buzzing with customers.

Recruited from Yale University, Fassler directs Notre Dame’s program in sacred music. It has no single home nor its own performance practice space, and 15 years ago it didn’t even exist. Now it oversees nine choirs, including a youth group with 300 local kids, and has seen its applicants jump five-fold to about 100 a year. Graduates find jobs in parishes, arts organizations and academia, and “we have a 100 percent placement rate,” Fassler says.

- Brave New Campus

- Notre Dame's 21st Century Building Boom

- Seven Tenets for Campus Planning

In recruiting her to South Bend from New Haven, University leadership promised Fassler financial support to build the department. But not a building.

Then, about four years ago, she got a call from Rob Becht, who directs the budget for the College of Arts and Letters. “He called me into his office and said, ‘What would you think of a music building on the south side of the stadium?’” she says. “I think he thought it would be a hard sell to me” — football and sacred music, “we’re odd bedfellows.” But, says Fassler, “I thought it was incredibly cool. You have 80,000 people streaming into those games, and you have to think about what they’re going to see. They’re going to see all this performance space, and they may want to come back for that.”

Around the same time, Dan Lapsley received a call from Dan Myers, then associate provost (and now provost of Marquette University). “We met out on the main quad, and he said, ‘I have a crazy idea,’” Lapsley recalls. “‘They want to put academic buildings by the stadium. Do you want to be part of it?”’

Then chairman of the psychology department, Lapsley and his 40 colleagues were based in Haggar Hall but spread over another six buildings and a few locations in South Bend. For years, a program for Indiana University’s medical school had been sharing space in Haggar’s basement. “They were cutting cadavers in there,” Lapsley says. Lab space was antiquated and department collaboration hampered. “I said yes right away,” he adds. “I didn’t even go back to the department.”

For some faculty, those initial calls were a personal introduction to the Campus Crossroads Project. The three separate buildings around the stadium together represent the University’s single biggest construction project ever, and they were going to go up fast. Given the timing of those faculty calls, it’s pretty clear Notre Dame’s leadership knew they were going to put up those buildings even before they knew for sure what would go in them.

Notre Dame is like a small city — in fact, when the 8,500 undergraduates are on campus, it is bigger than about 50 other cities in Indiana. And it had been sprawling. McCourtney Hall, opened in 2016 as a new research center for the molecular sciences and engineering, sits northeast of the Hesburgh Library, well past where Juniper Road marked the edge of campus a few decades ago.

To the south, the DeBartolo Performing Arts Center had long ago hopscotched the stadium, with the $64 million complex opening in 2004. The growth also spread off campus with the new University innovation center across Angela Boulevard; the restaurants, shops and condos at Eddy Street Commons (Notre Dame owns the land under the development); and the new houses farther south into the residential neighborhoods of South Bend, today many of them home to faculty.

The University’s top leadership — including Jenkins, Executive Vice President John Affleck-Graves, Provost Thomas Burish ’72 and athletic director Jack Swarbrick ’76 — saw an opportunity for growth closer to the center of the expanding campus: Notre Dame Stadium was used perhaps eight times a year. New buildings around the stadium could make use of that acreage, providing room for expansion without spreading the campus footprint. And updating the stadium could enhance the game experience for fans. That, however would come with questions about whether those buildings were really just outrageously expensive scaffolding for the new luxury floors and gigantic video screen, and alumni concerns about the increased contributions for season tickets to help pay for it all, as well as the very expensive new premium seats that many incorrectly thought were skyboxes, something Notre Dame has long resisted.

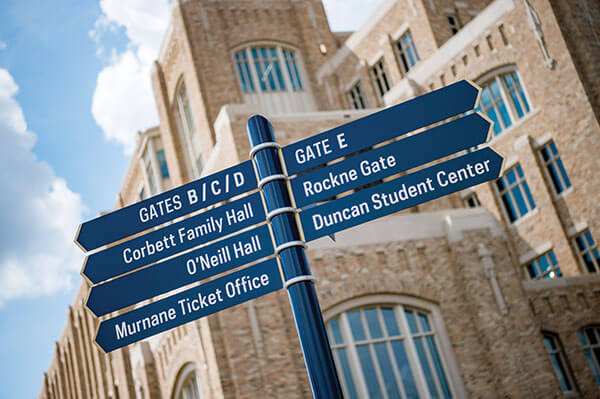

The Campus Crossroads project, which broke ground in the fall of 2014, was part of a strategic plan with a 10-year outlook. The plan had identified need for a new student center, with more exercise facilities, meeting rooms, social space and eateries, as a top priority. Some consideration was given to placing it at Stepan Center, but that was deemed too far removed from campus foot traffic. Attention quickly turned to the stadium and with that, the first of three buildings — Duncan Student Center — was set.

The music and sacred music departments had long outgrown Crowley Hall and did not have dedicated recital space. With the DeBartolo Performing Arts Center anchoring the south end of campus, it was decided to add music to the trio of buildings at the stadium and further turn that area of campus into a magnet for performing arts. That accounts for O’Neill Hall, which fans will see as they enter the Leahy gate on game day.

Psychology and anthropology didn’t necessarily have to be near the stadium, but the departments often collaborate, and the necessity of having the side of the building abutting the stadium windowless was useful for the departments’ labs. Psychology researchers also often work with South Bend residents, and the new location would make it easier for the locals to get on campus. Those needs determined the final building, Corbett Family Hall, which also includes digital production space for game day broadcasts, student projects and video creation.

The Crossroads project represents the most dramatic change to Notre Dame’s landscape in generations. If you love Irish football, the stadium enhancements are long past due and spectacular. If you worry that football could dominate academics, the buildings have made the stadium nearly disappear. They tower over the house that Rockne built, large rectangular slabs obscuring much of the outside curve of the stadium on all but the north side.

The University’s leadership is mindful they were playing with emotions with the project. “Every alum comes at this from their own perspective. Some feel we have too much emphasis on sports, some feel there’s too little,” Affleck-Graves says. “As long as we have both, we’re probably in the right spot.”

The mix of football and academics is fraught at Notre Dame. So too has been the expanse and sheer pace of the new construction — with eight new buildings opening between August 2016 and August 2017. There is no question that the campus is more opulent now than a few decades ago. Those cushy premium seats — 3,264 of them, some on swivels — are an unprecedented stadium addition. Meanwhile, tuition is continuing to rise and with it some growing unease. Two weeks after my June campus visit, Notre Dame and Father Jenkins were featured in a New York Times story headlined, “Does God Want You to Spend $300,000 for College?”

I wanted to get a sense of what alumni are thinking about all these changes and emailed a dozen or so that I have known over the years for their impressions. Their answers were not unlike some of the questions University officials say they hear from alumni, too. One significant donor, who had just returned from his 50th reunion, wrote back that “there was lots of discussion about construction and money.” Among the questions from his classmates were: “Has the emphasis on bricks and mortar put a squeeze on monies available for the improvement of faculty talent? Or for monies that could be used to help control the wildfire of tuition increases?”

One of my classmates, a second-generation alum, asked, “What is motivating the building? I fear it’s a reaction to what I’d call an arms race. When is enough enough?”

I was equally struck by commentary with a different perspective from Matt Emerson ’08J.D., who wrote about Campus Crossroads in the Jesuit publication America. “My first reaction was similar to many others, a reflexive ‘wow’ at the magnificence of the project and a marveling at the cost,” he wrote. “But it would be a mistake to see the Campus Crossroads project as a mere expansion, as simply another sign of progress at a leading school. In implementing the Crossroads project, Notre Dame is making a dramatic statement about the nature and future of education.”

Almost from the start, Crossroads captured the attention of sportswriters instead of education reporters. They portrayed it as an expansion of the stadium. In fact, even with those new, visible premium seats there will actually be about 2,000 fewer seats overall because 23 miles of old redwood bleachers have been replaced with wider and deeper benches that won’t cause splinters. Less noticeable but critically important is what is beneath those seats: a new flooring membrane to protect the stadium bowl.

Along with the renovation, pricing for tickets changed this year to make end zone seats more affordable and midfield seats more expensive, the idea being the better the view the higher the price. The overall goal was to keep ticket revenue the same and make some seats cheaper for families. Along that same vein, hot dog and bottled water prices dropped this year.

During the stadium tour, Marsh shows me some other features: a new but much smaller tunnel for visiting teams so they won’t share the home team’s path to the field; patios off the premium level; and inside meeting space and dining areas that will be open for games and also be available for entertaining, receptions and business events on non-football weekends (becoming a new source of University revenue) and used for class projects during the week. All the stadium restrooms were updated, nearly 150 TV screens installed in the concourse, and new cellular and Wi-Fi networks added for fans. And perhaps the biggest change — a 96-by-54-foot video screen on the south end zone that will replace the old scoreboard to the north. The old board’s removal will enhance the view of the Jesus mosaic on the Hesburgh Library and the new screen will offer replays and close-ups of action on the field — but, University officials promise, no “kiss cams” or commercials.

“It’s a new era, more sophisticated,” Marsh says as he looks out at the workers, specks of lime green against the stadium bowl. “And no less a commitment to excellence than Father Sorin had.”

There are 24 elevators in the stadium and an elegant bar for those premium-seat holders. The old bleachers with their seat numbers panel some of the walls. The roofs are covered with environmentally friendly plantings, which also is planned for the Joyce Center when its roof is replaced next year.

The Crossroads name led some alums to question whether the administration saw the center of campus gravity tilting toward the stadium area instead of the main quad and the Dome and the Basilica. “In retrospect, I don’t know if Crossroads was the best choice of names,” concedes Affleck-Graves. No matter, it’s likely that students and others on campus soon are going to tell each other to meet at Corbett or that a class will be in O’Neill — “Crossroads” will be just too vague for anyone to pinpoint.

Those buildings appear as notable as any could desire. Experts are refining the acoustics of the performances spaces for the music and sacred music departments. The student center includes a sloped gathering place that faces an enormous television screen, which will likely become a popular spot on away-game weekends. More importantly, the career center will operate there with plenty of new space for visits from prospective employers. In many ways it will be one of the most cross-disciplinary places on campus.

Given that, perhaps Emerson’s article in America made the public case for the Crossroads project better than the University itself. What he was getting at — and this can be said for all the campus building going on — is that the new construction represents a renewed investment in the importance of the undergraduate experience for young people. At a time when online classes are all the rage and some futurists predict the demise of the residential college campus, these buildings signify a different view and a distinct set of priorities.

“This is a great way to create more opportunities for the academic units to do wonderful things,” says Peter Smith, chairman of the music department. He is helping design the music facility in O’Neill Hall that he foresees will serve Notre Dame for another century and whose location will mean thousands of people will see it and learn more about the music department’s accomplishments. “It’s another way for Notre Dame to exploit the investment in football for the University’s core mission,” he says.

The emphasis on undergraduate life and especially on Catholic character has long defined the University. A student center with a rock-climbing wall is a bow to the educated consumers that many college-bound young people have become. So too are the new residence halls, even though the student body isn’t growing, and the chapel in each hall, adding to the buildings’ price, though Notre Dame would have it no other way. Many of the new buildings clearly are a recognition — and embrace — of Notre Dame’s vision for itself as a true research university, an evolution begun during Rev. Theodore Hesburgh’s tenure as president that is moving even faster now.

“The heart of Notre Dame will always be the education of young people,” Jenkins told me. “But research is part of a university. Professors don’t just pass on truths, they discover them. The best ones are on the front lines of discovery.”

To attract that faculty requires salaries and facilities. “It costs a lot because it costs a lot to educate at a high level,” he says. “The question for me is not the absolute dollar amount, but what are we spending it for?”

In some ways, Notre Dame’s latest ambitions match the progress of U.S. Catholics over the past century. The integration of immigrant Catholics into American society, their professional success and the accompanying philanthropy, has both mirrored and helped create the University’s growth.

Major gifts have increased substantially, and the endowment was $10.4 billion at the end of fiscal 2016. The percentage of alumni donating to the University has slipped in recent years, however, as those with more modest means may be wondering if their contributions might have more impact elsewhere.

Some of the alums I emailed for impressions of Notre Dame described a seemingly constant barrage of fundraising and ever-escalating required contributions in order to purchase football tickets. That, too, is representative of the new era for the University.

The increased contributions for football tickets were a deliberate decision, Affleck-Graves says — the money raised going for stadium renovations with the thinking that those who go to games should bear some of the cost.

And as large as it is, the endowment is not an enormous piggy bank to be tapped as needed. University officials describe it as more of a series of contracts — gifts for specific purposes over time. Each new building or capital need or scholarship fund often requires a new donation, and most new construction now under way is funded by benefaction. Donors are asked for 110 percent of the cost of building, with the extra 10 percent invested for future renovations. And ground isn’t broken until three-fourths of the gift is in hand.

So, as my classmate wondered, when is enough enough? The answer is, probably never.

photo: Barbara Johnston

photo: Barbara Johnston

And it seems like it has always been so. Think those contributions for season tickets are high, that premium seats highlight the haves versus the have-nots? Well, private boxes were on sale before the stadium was completed — nearly a century ago. The Notre Dame Alumnus reported in 1929 that excavation had finished and that boxes were being sold for 10-year periods and “with the ownership of a box go many privileges.”

Other classmates have complained to me of ham-handed contribution requests — out-of-the-blue calls from campus for a large donation. Still, the University seems to make some attempt at decorum and is giving up millions of potential revenue by not allowing advertising inside the stadium or on that new gigantic video screen.

Where to draw the line can be difficult. “People have enormous passion for this place, and in people’s minds we represent a certain ideal,” says Affleck-Graves. “It’s hard — because everybody’s perception of ideal is slightly different.”

Those ideals, of course, originated with Father Edward Sorin, who built a fledgling school on the Indiana prairie 175 years ago and dared to call it a university. And he knew something about building. When an 1879 fire destroyed many campus buildings, Sorin, who had gone on to become superior general of the Congregation of Holy Cross, rushed back to survey the damage on the campus he had founded.

The French priest, sounding not unlike the Chicago architect Daniel Burnham, looked at the burnt-out remains and said, “I dreamed too small. . . . We will begin again and build it bigger.”

Daniel LeDuc is a Washington, D.C.-based editor and writer who spent three decades at the St. Petersburg Times, The Philadelphia Inquirer and The Washington Post, and taught in Notre Dame’s Washington Program.