Soldiers of the 45th Infantry Division dreaded the series of Sicilian peaks that impeded their advance on Axis defenders in July 1943. The mountain range’s nickname — Bloody Ridge — denoted the carnage caused by the young Americans’ attempts to knock their opponents from their perches, even as German bullets and shells cut swaths through their ranks. The dead lay in grotesque forms on the ground. Wounded men cried out for aid. Bloody Ridge was no place for combat veterans, let alone raw recruits, but few would shrink from the job they had to do.

Photo: 45th Infantry Division Museum

Photo: 45th Infantry Division Museum

The petrified soldiers of the 45th knew they could count on one man who would be there for them through the peril: their unit chaplain, Father Joseph D. Barry, CSC, who crawled through a dry creek bed during the fighting to reach the injured. He paused over each fallen man, and either heard hurried confessions and gave absolution to the Catholics, or said quick prayers those who weren’t. His actions during the five-day battle so moved the soldiers and Barry’s fellow officers that the Army soon awarded Barry one of its highest honors, the Silver Star.

Serious-minded, sturdy and competitive by nature, Barry ’29 had always compensated for his 5-foot, 3-inch frame with intensity and grit. Born to Irish immigrant parents on October 7, 1902, in Syracuse, New York, Barry had excelled at sports. A key member of his high school baseball nine, Joe Barry the quarterback also led the school’s football team to the city championship.

He matched his devotion to athletics with academic achievements and a desire to help others. In the classroom, he listened to the nuns spin their stories about the summer classes they had taken at Notre Dame and the joys of religious life. Seeking an occupation that privileged the community over individual attainment, he later enrolled at Notre Dame and would spend an additional four years at the Congregation of Holy Cross seminary near the University’s grounds before his ordination in June 1933.

Father Barry expected a future of mission work, parish labors and teaching at Holy Cross schools, but Germany and Japan would soon alter his path. As war once again tossed Europe into chaos in 1939, he concluded that he needed to put himself where others most needed religious guidance and support: the military. Yet joining the Army in April 1941 with the assent of his religious superior meant embracing a quandary, for from that moment on, he became a man of peace in a sphere of violence. He would walk a tightrope between those disparate worlds, all the while trying to maintain his balance. After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor that December, he became one of the 29 chaplains and six missionaries affiliated with the congregation and the University who would serve American soldiers and civilians during World War II.

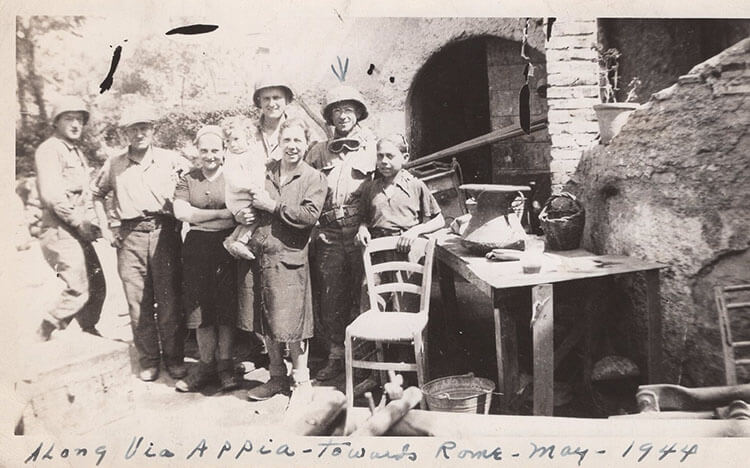

Once he completed chaplain school, Barry was attached to the 157th Regiment, a Colorado National Guard unit that was part of the 45th Infantry. The unit saw action in Sicily and at Anzio on the Italian mainland before campaigning into southern France and Germany. Throughout, Barry maintained an extensive correspondence with his superior at Notre Dame, Father Thomas A. Steiner, CSC, and others back home. In every letter, he shared his observations about the fighting, referring to the men he served not as soldiers, but as his “boys” or “lads,” who wanted nothing more than to end the ghastly business and return home.

The priest whose men admiringly called him a “foxhole chaplain” spent part of his time at aid stations removed from the fighting where he could assist the wounded, but he preferred to be where he believed his boys most needed him — at the front lines. He celebrated the Mass, heard confessions and prayed with the frightened and the dying. Once he consoled a new soldier who expressed fears about how he would handle the fighting. If he were to die, and if Barry thought he had conducted himself honorably, would the priest tell his family that he’d carried out his duty? When German fire cut down the youth, Barry rushed to his side, cradled the mortally wounded boy in his arms and whispered into his ear, “Remember how we talked last night. Here it is. And I can say you were a good soldier.”

Chaplains share the life of the men they attend, and Barry succumbed to the same fears and doubts that assailed those soldiers. He shivered in the same cold; he, too, trod wearily along dusty roads. His comforting words to the fatigued men came from a human being staring into the same abyss. “When you are crouched against a thick wall while the air splits and the earth quakes,” he wrote Father Steiner, “there is one and only one thing to do: pray, boys, pray.”

That Christmas, longing to be back home, he typified the spirit of the season by turning down an invitation for Christmas dinner that most soldiers would have given a month’s pay to accept. His commanding officer asked Barry to accompany him to dine with General Mark W. Clark, commander of the United States Fifth Army. Barry politely declined. Instead, on Christmas Eve, in a desolate cave, Father Barry celebrated Mass surrounded by soldiers from the 157th.

Barry enjoyed a pause from combat when the regiment entered Rome the following June and everyone received a 48-hour pass. He smiled when his boys asked whether he would visit Pope Pius XII. “To hear my kids talk, you would think all I had to do was to go up to the front door, knock, and say, ‘Is the Pope in?’” In fact, those hopes materialized when Pius XII addressed Barry and 63 other chaplains. After addressing the group, the Holy Father spent a moment with each chaplain, asking his name and hometown. When he learned Barry was from Notre Dame, he smiled and made reference to his October 1936 visit to campus, when he was still Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli. “It is very beautiful,” the pontiff told the priest. “I was there, you know.”

Photo via Congregation of Holy Cross Province archives

Photo via Congregation of Holy Cross Province archives

Barry’s letters became his link to all that was not war — to Notre Dame, to friends, to laughter and civilization. He referred to the peace he found at the Grotto and described the campus as a magnet that drew his thoughts to Notre Dame. He loved reading about Irish football victories and celebrated whenever sportswriters picked them as the No. 1 team in the nation. “That’s the kind of news that keeps my morale up . . . up . . . up for Notre Dame,” he wrote Steiner.

He would need those infusions of spirituality and levity, for in the spring of 1945 he came face to face with ultimate evil. On April 29, the 45th received orders to head to the Dachau concentration camp, where, between 1940 and 1945, at least 28,000 people were slaughtered. Appalling images lay before Barry and his regiment. Soldiers “who last week still wondered why we fought the Germans and their beliefs,” one of the division’s newspaper reporters wrote, “got their answer at the Dachau prison camp, where death claimed victims by the carload and murder was a wholesale sadistic business.”

Barry had read about the gas chambers and preferred to avoid them, but believed that if anyone then in Dachau had a duty to observe the scenes, a chaplain was that person. When the priest arrived at the chambers, he found emaciated bodies everywhere. “The stench was such that you could not stand it long,” he said in an interview 35 years later.

Standing among the bodies of men, women and children, Barry confronted the very core of his convictions about human beings and the God who made them. If he was correct in thinking that man was good, how could such depravity exist? If he was wrong, he would be admitting that the foundations of his religious beliefs were frayed at best, rotting at worst.

War’s end in Europe on May 8, 1945, completed 511 days of combat for Father Barry. “I need not tell you that I am most eager to get back,” he wrote Steiner. “I believe I have seen my share of blood, death, mud, hunger and cold.” Yet years later he would recall his military service as “the happiest years I spent in the priesthood” because he had worked with such courageous men.

Barry returned to the States in September 1945, arriving in Boston in plenty of time to join the football team, fresh from administering a 34-0 thrashing to Dartmouth, for the train ride back to Notre Dame. A relaxing journey ended at South Bend’s station, where University luminaries provided a warm homecoming. “Local Priest Modestly Returns as War Hero,” the South Bend Tribune proclaimed on October 22.

But Barry’s wartime experiences had changed him, and he doubted whether he could ever be the same. “I fear I’m going to be very impatient when I return to the States and hear complaints about domestic troubles, low wages, sore arms and stiff necks,” he had written to his friend, the campus historian Father Arthur Hope, CSC.

After leaving the Army, Barry held a variety of posts at Notre Dame — hall rector, football chaplain, prefect of discipline. In 1963 he left to begin a 19-year stint as chaplain and religion teacher at one of the congregation’s largest high schools, Archbishop Hoban in Akron, Ohio.

The ravages of Dachau had assailed Barry’s conviction in the goodness of man. It took many years, but with the passage of time and the experience of rewarding work among students in an era of peace, the priest rediscovered his optimism.

He died on September 25, 1985, at the age of 82. It is fitting that he rests in the Holy Cross cemetery not far from the Grotto, for it was his beloved Notre Dame that had always motivated him to his highest standards. He may not have saved lives with the weapons of warfare as his boys had done in combat, but he had rekindled hopes and rescued futures with the tools of religion. In his tenure as Army chaplain, laboring alongside young men in the cauldron of battle, Father Joe Barry exemplified those principles that adorn the eastern door of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart: “God, Country, Notre Dame.”

John Wukovits is a World War II historian who has written several books about that conflict. This piece is adapted from Soldiers of a Different Cloth: Notre Dame Chaplains in World War II (University of Notre Dame Press, 2018).