To understand my friend Kurt Petersen ’87, one of the most innovative labor leaders of his generation, you have to grasp how much he likes winning.

And it’s a lot.

Kurt is a co-president of Unite Here Local 11 in Los Angeles, and he is currently leading the largest hotel workers’ strike in United States history.

The hotel owners across the negotiating table should be wary of the Kurt I’ve known for 40 years, the one who plays games like his hair — the little he has remaining — is on fire. The one I remember out behind Carroll Hall playing tackle football in white leather Converses and boot-cut jeans, plucking a pass out of the sky and taunting defenders as he crossed the goal line.

These days, Kurt has traded football for tennis, but losing still isn’t an option. He plays high-risk tennis, charging the net at every opportunity. He competes in a weekly game with another Notre Dame classmate, Kevin Clegg. “I warned [the people we play with] that he had the most aggressive style of tennis and was the most competitive person I’ve ever met,” Kevin says.

Kurt’s will to win is central to his calling as a labor leader. In Unite Here’s monthslong strike against more than 60 hotels in Southern California, he is leading a campaign to increase the hourly wage of the union’s members by 40 percent.

It’s an aggressive, high-risk strike.

And, as usual, Kurt Petersen is winning.

This profile is not objective. Kurt is a close friend, and I believe unions can help establish a more equitable nation. I want you to know how the Kurt I met at Notre Dame has spent the past 40 years preparing to be the labor leader he is today.

The Kurt I knew when we were students practiced a progressive Catholicism that only deepened at Notre Dame. He was adventurous, unafraid to take risks. He loved to laugh and to make people laugh. He was an avid reader, who applied what he learned to real life. He was a leader — but a collaborative one. And, of course, he reveled in defeating whatever opponent was at hand.

At Notre Dame, Kurt found much to prepare him for his life’s work. In his first weeks on campus, he met Anne DeWald Petersen ’87, who has been his partner in helping working people get a fair shake for four decades now. The pair was simpatico from the start; many of their dates were volunteer sessions at the Center for Social Concerns.

I met Kurt in a government class. We read Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau. Those writers showed us that political power isn’t simply granted. You had to take it, and you had to use it.

Dorothy Day inspired Kurt with her life of service. He read her memoir, The Long Loneliness, and then spent a summer living at a Catholic Worker house in Milwaukee. “I’m still in touch with the folks there,” Kurt says. “Watching them dedicate their lives to voluntary poverty and service to the poor, because they believe that’s what the Gospels called them to do — well, I wish I had as much commitment as they do.”

“Economic Justice for All,” a 1986 pastoral letter from the U.S. Catholic bishops, also influenced Kurt. Citing Jesus’ focus on the downtrodden, the letter questions capitalism’s course. Ultimately, the bishops conclude, “We find the disparities of income and wealth in the United States to be unacceptable.”

Kurt internalized the bishops’ point of view. “If you read the Gospels, it talks about Christ liberating prisoners and advocating for the poor,” he says. “And at that moment when we were at Notre Dame . . . it was important to hear that from the Church.”

Kurt and I remained mere acquaintances until we studied abroad in the University’s London program in 1986. I introduced Kurt to my friends there, and we all hit it off.

While overseas, Kurt amassed lasting memories. With Anne, who was studying in Rome, he saw an indelible Pogues concert in London on St. Patrick’s Day. He witnessed Pope John Paul II celebrate the Easter vigil Mass in St. Peter’s Basilica. But a moped ride in Nice, France, might have been the most memorable experience of all.

On that day, Kevin, Kurt and I rode sputtering, rented mopeds for hours along the Mediterranean Sea and into the foothills of the Alps. We rode past concrete bunkers left over from World War II, stared out at the water and bathed in an exhilarating sense of freedom. We felt like Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper in Easy Rider, minus the Harley horsepower.

On an overnight train to return to London, one of us suggested a similar journey around our home country. It seemed like a pipe dream. But Kurt has a way of turning a vision into reality.

A year later, diplomas in hand, we left South Bend, determined to take the road trip we’d been dreaming of. We caddied, waited tables and delivered pizzas. By September, we had amassed enough money to buy a $300 van, a tent and a video camera.

That summer, Kurt read William Least Heat-Moon’s Blue Highways, which chronicles the author’s travels on America’s backroads. That concept provided a structure to our trip: We stayed off interstates, sticking to rural two-lanes.

We hit the road in late summer. We meandered through the Midwest, across the Mississippi River and back again and drove up into Canada. We pitched our tent on the Gaspé Peninsula, along the banks the St. Lawrence River. This beautiful stretch of land that none of us had ever heard of blew us away.

Fleeing the cold, we turned south, following the logging roads through New Brunswick and into Maine. We

traveled down the Eastern Seaboard and into the Deep South.

The journey was a model of collaborative leadership. Each day the driver chose the day’s destination and controlled the tape player: Kurt invariably chose U2. Another of us rode shotgun and acted as navigator, giving directions from an atlas. The third sat in the back — free to look out the window at whatever happened to be rolling by: pine forest, farmland, the Atlantic Ocean.

For Kevin and me, aimlessness was the point. We were killing time until we took real jobs. We often passed the time by filming what we thought were David Letterman-like skits. One of those bits consists of video footage of Kurt walking the length of a Philadelphia block while Kevin does an improvised voiceover: “This could be like the opening of a new series, The City Priest, starring K. Petersen. Sure he’s tough, sure he’s rough, sure he breaks some laws, but he believes in a higher law.”

Kevin’s characterization of Kurt as a priest wasn’t random. Kurt was considering the priesthood, and he arranged visits to two Jesuit seminaries during our travels. He was using the journey as a retreat of sorts to consider next steps in what he knew would be a life of service. Kevin and I shook our heads about his contemplating that choice when he had a girlfriend like Anne, who was spending that year in the Bay Area working with Holy Cross Associates.

On our days in the driver’s seat, Kevin and I chose destinations like Hibbing, Minnesota, where we hunted for Bob Dylan’s childhood home, or Springfield, Massachusetts, where we paid homage at the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

Kurt’s selections were different. He chose Montgomery, Alabama, the site of Martin Luther King Jr.’s bus boycott. He also took us to MLK’s church in Atlanta. And he drove to Selma, Alabama, where a policeman fractured civil rights leader John Lewis’ skull near the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday.

Kevin remembers those visits agitating and inspiring Kurt. “I think he’s motivated by this deep sense of not only justice, but fairness,” he says. “He’s driven by a low-grade rage. When he feels he’s on the right side, and there’s injustice and something unfair, he is highly driven to change that.”

In January 1988, Kevin and I pointed the van west and explored the other half of the country until our money ran out. Kurt headed to Baltimore, where he taught at a Catholic grade school for 18 months before heading to Yale Law School

His law school years showed what a workhorse he is. On top of classwork, he spent a summer in Guatemala and then wrote a book, The Maquiladora Revolution in Guatemala, about the exploitation of garment workers.

He found his labor of love when he joined a legal clinic at Yale, which represented people who couldn’t pay for lawyers. Kurt was thrilled when he and fellow law student Michael Wishnie got an assignment to represent a fledgling union in New York City. He also liked that he could visit Anne in Manhattan, where she was getting her master’s degree in social work from Columbia University.

Today, Wishnie is a Yale law professor who oversees that same clinic. He likes to tease Kurt by taking full credit for his career. “I can say that Kurt learned collective bargaining from me,” he says.

“He was interested and passionate about it,” Wishnie adds. “He cared a lot about the work and about the people. This wasn’t just about the terms of the contract and words on the page, but about people’s lives.”

Kurt found that working for a union fed two sides of his personality. It served his belief that the Gospels call us to serve the forgotten. It also scratched his itch for a good fight. He found it was an asset at the negotiating table to be 6-foot-2 and 220 pounds — and intimidating as hell when he wants to be.

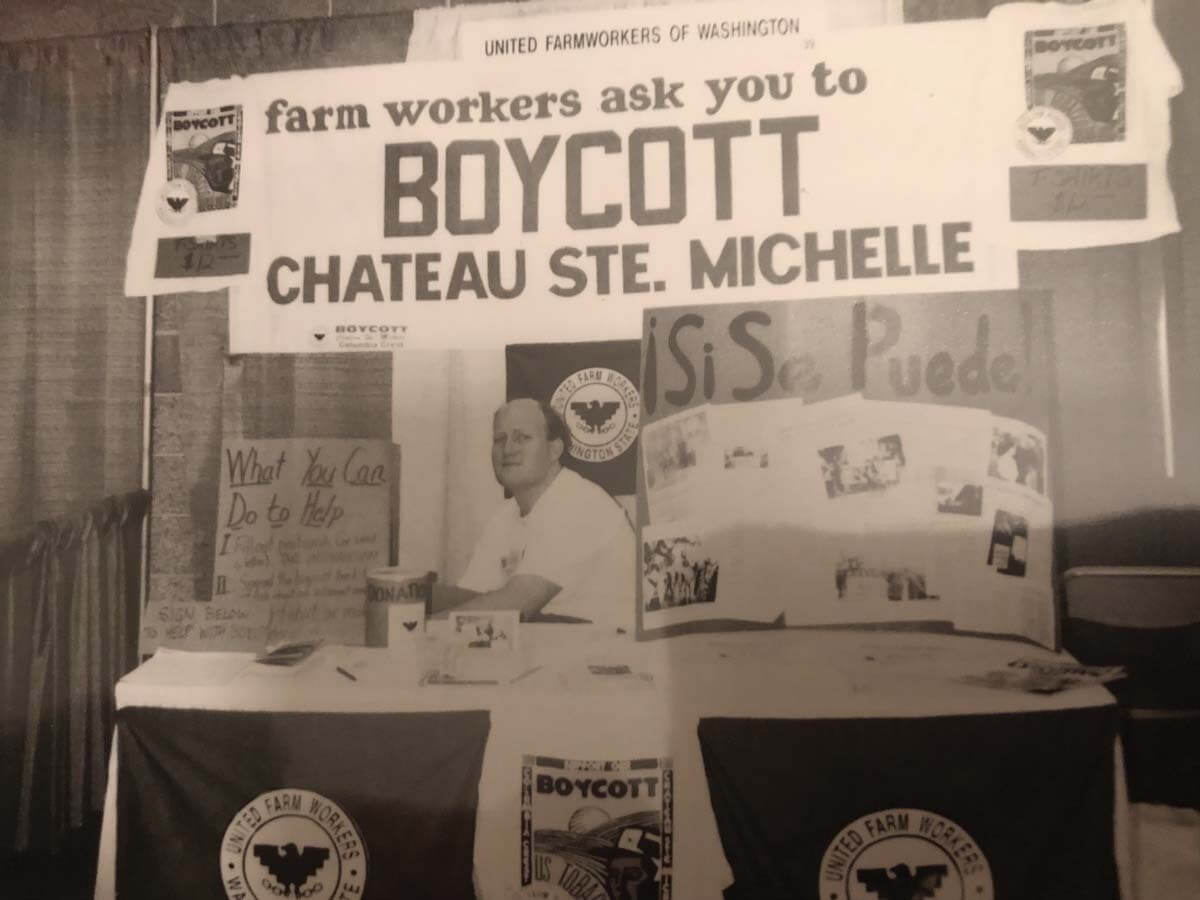

Representing that union changed Kurt’s life. He never took the bar exam to become a practicing attorney. He never became a priest, either. Instead, after finishing law school, he married Anne in Notre Dame’s Log Chapel. The couple “honeymooned” in the Yakima Valley where Kurt had secured a role helping the Washington state United Farm Workers in their fight to unionize the state’s leading winery.

Anne remembers driving with Kurt into the small town of Sunnyside, Washington, which would be their home for the next few years, and going directly to the union’s office. Kurt introduced Anne as his esposa, and she instantly felt part of the team — and firmly a part of her husband’s life. The union helped her put her social work degree to use by finding her a job teaching special education at an elementary school.

When Kurt arrived, the fight for a contract with the winery was six years old. He was part of a team that recruited labor leader Rosalinda Guillen to lead the fight. Watching Guillen, Kurt witnessed the power of fearlessness and of making demands unapologetically.

In December 1995, Kurt saw the farm workers secure a contract, the first agricultural labor agreement of its kind in Washington. A jubilant party followed. To this day, he keeps handy a photo of scores of workers celebrating the victory.

“It wasn’t just a breakthrough for those couple hundred workers,” he says. “It was a message that what this industry was built on, which was basically indentured servitude, could change.”

Despite the victory in Washington, the labor movement as a whole was flat on its back. Due to a number of factors, union membership declined from about 20 percent of the workforce in 1983 to 10 percent in 2002, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But Kurt was a true believer, and the surprising gains delivered in 2023 by the United Auto Workers, the Writers Guild of America, and the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists were a long way off. The Petersens’ next stop was Los Angeles. Anne was pregnant with their second child. Kurt joined Unite Here Local 11, which represents food service and hotel workers. Anne again found a teaching job.

In rising through the ranks at the union over the past three decades, Kurt brought his full-on belief in the labor movement, his collaborative leadership style, his capacity for work, his constant learning — and his love of winning.

He started as an organizer. It’s a challenging job, especially when you look more like the bosses than the workers. The workers that the union strives to organize are typically Spanish-speaking women from Mexico and Central America.

Workers who step up to organize their colleagues put themselves in management’s crosshairs, so they must be able to trust the union’s representatives. Even though federal laws ostensibly protect the right of workers to organize, companies and the union-busting firms they work with have discovered little downside to firing workers who agitate for a union.

“No matter how hard we say it will be . . . they always come back and say, ‘Kurt, you never said it was going to be that hard,’” he says. “‘You never told me they would threaten my job, or they might tell me I’d be deported, or they might ostracize me, isolate me.’ Our job is to keep people inspired and confident that we will win.”

So how does a man gain hotel workers’ trust when he looks more like an executive than a room attendant? Kurt builds rapport by going for the laugh. His fallback is self-deprecation. He also likes to tease members about “fake football” (soccer) compared with “real football” (the kind Jerome Bettis played).

“Kurt’s funny in English, but he’s twice as funny in Spanish,” says Ada Briceño, a fellow Unite Here co-president.

“That’s because my Spanish is horrible,” Kurt replies.

Although Kurt has embraced several things about California — the weather, kale smoothies, fine wine — his wardrobe remains Midwestern. Every day he wears a button-down shirt, chinos and brown brogues. He leans into his not-from-here persona and, in heavily accented Spanish, occasionally refers to himself as el tio loco. And this is one crazy uncle who gets results.

Lorena Lopez, the union’s organizing director, however, remembers being skeptical of Kurt at first. “Seeing a person from a different background, different in comparison to the workforce, made it even more difficult to believe that by organizing the union we will succeed or fix our problems,” she says. “But over time, seeing victory after victory, it was palpable that his vision was right — that by organizing and by being strategic, we could change things.”

Kurt’s devotion to Unite Here infuses his family life, his social life, even one-off encounters with people he barely knows.

In polite company, most people shy away from the controversial topics. Not Kurt. At a get-together years ago, a woman asked him what he did for a living. After he responded, she mentioned that her aunt also did something with unions, and she named a firm that busted them.

Kurt didn’t hesitate to reply. “Your aunt’s going to hell,” he said.

In full disclosure, Unite Here has even had some conflict with the University of Notre Dame. In 2010, the union worked with a group of students who conducted a short hunger strike. They were protesting the University’s stake in a national hotel investment and management company that owned properties in California, where the union was trying to organize workers who said they were being treated unfairly — and not in line with Catholic social teaching.

The hunger strike factored into an eventual meeting between a company representative and union leaders, but it did not sway Notre Dame to divest from the company. Noting that the hotels eventually unionized, Kurt says, “We won anyway.”

Social justice is never far from his mind. From his extended family at Notre Dame, he has recruited five graduates to work for Unite Here Local 11 over the years. Similarly, three Yale Law School graduates currently work for the union.

Kurt and Anne named their two sons for their heroes: Matthew Day, after Dorothy Day, and Joseph Oscar, for St. Oscar Romero. One of their dogs is Huelga — “strike” in Spanish.

Some days quality family time meant walking picket lines together. Their daughter, Hannah Petersen ’16, is now a Unite Here organizer. She recalls at least one protest from her childhood when workers faced off against police on horseback and in riot gear.

She also recalls peacefully canvassing with her father. “I remember always at the end of it, I’d get an ice cream cone from an ice cream truck,” she says. “It’s an important memory of learning about what my Dad did, but it was also probably more important to me to spend time together.”

Capturing Kurt’s attention can sometimes be a challenge. Anne recollects how thrilled Kurt was when he brought home his first mobile phone. “He goes, ‘This is going to be so great,’ because he thought it would make him work less,” Anne says. “And of course, that was completely wrong.”

Too often that phone simply enabled Kurt to work at home. Or when he went out to dinner. Or at the lacrosse game or Irish dance recital. “He might have been on the sideline on the phone talking to the head of Hyatt Hotels,” Anne recalls, “but he was right there. He’s not missing stuff like that.”

Kurt knows he found a rare partner in Anne. “She’s the best person I know,” he says. “She’s a role model. She’s a special ed teacher. Every day she goes in and leads with enthusiasm and love. She’s a remarkable example for all of us. Watching her just constantly be positive and helpful and caring is really something I try to emulate, but not very well.”

In 2017, Kurt won an election to become one of three co-presidents of Unite Here Local 11. Today he leads the union along with Ada Briceño and Susan Minato, both of whom rose through the union ranks with Kurt.

“Our union does two things really well,” Kurt said. “We believe in winning, and we believe in training leaders and replacing ourselves.”

“It amazes me how completely democratic and membership-run the union is, which is remarkable,” says Tim McOsker ’84, an LA City Council member. “It’s not for show, and it comes from leadership. It comes from Kurt.”

The triumvirate arrangement is unusual. But Kurt has participated in power-sharing models before. On the road with Kevin and me, he uncomplainingly shared driver duties. In battling the Washington winery, he saw union leaders yield to Rosalinda Guillen’s expertise, and that arrangement delivered a victory.

Unite Here is also winning. As a group, the three co-presidents enable the union to pursue a broad strategy of winning political elections, lobbying for legislation and prevailing at the bargaining table.

One recent success: The city council passed a law with union support that included a provision requiring developers to replace the housing they displace when building a new hotel.

“It’s a remarkable piece of legislation that will truly prioritize affordable housing over luxury hotel development,” Kurt says.

When necessary, the union also goes on strike, as it did last summer. The ongoing campaign is delivering huge contractual gains for Unite Here’s members.

Launching a strike is like going to war. The fight is usually won or lost in the planning, before a shot is even fired. Kurt prepared in part by reading former Wall Street Journal and Washington Post reporter Thomas E. Ricks’ recent book, Waging a Good War: A Military History of the Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1968, for its account of how the movement won its battles. When calling the strike last summer, Kurt drew on his knowledge, experience, tenacity and thirst for justice. He’d been training for the decision his entire adult life.

The Unite Here campaign targets more than 60 hotels in southern California, because in past negotiations Kurt and his co-presidents had made certain the contracts all expired on the same date. The strategy unites the bulk of the union’s membership in a common cause.

If the size of the strike was right, so was its timing, Kurt believes. The hotels, he says, had overreached in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the pandemic, hotel workers made sacrifices to do their jobs and support their families, with some laboring through the most dangerous days of the crisis and others laid off for months. When hotel guests began to return, many hotels tried to maximize profits by continuing to use skeleton staffs and eliminate daily room cleaning, which requires fewer workers.

“They got greedy,” Briceño says.

And what the hotel owners got in return was an angry employee base. “The pandemic was the catalyst, and it’s emboldened and empowered workers,” affirms Notre Dame historian Daniel Graff, the director of the school’s Higgins Labor Program.

The union has harnessed this fury by providing a clear goal to its members: a $5 hourly pay raise in the first year of the new agreement, which totals $10,000 annually per worker.

An important part of Kurt’s approach was to avoid a full-fledged walkout, because it was conceivable the hotels could wait out the union and eventually hire full staffs of replacement workers. Instead, union members struck in waves, walking out one day and returning to work a few days later.

Over the course of the strike, they have conducted more than 130 separate walkouts. The hotels can’t predict when strikes will occur, and it doesn’t make sense to hire new employees when their trained staff will likely be back on the job within a day or two. When union members do walk out, the picket lines are raucous. Workers march, bang drums and bark through bullhorns beginning early in the morning.

The union is a motivated army, and its simple message in the media helps recruit allies to its cause. The narrative has focused on affordable housing and how workers cannot afford to live near where they work. Some drive hours getting to and from work.

This message has resonated. In solidarity, members of the screen actors’ and writers’ guilds have walked picket lines with Unite Here. Soccer star Lionel Messi refused to cross the picket line and pulled his Inter Miami teammates out of a hotel where Unite Here was striking.

The negotiations have been tense, but union members have faith in Kurt’s unwillingness to back down. “He makes a demand, and he doesn’t move from it at all,” says Lopez, the organizing director. “I’ve been to a number of negotiations with him. It’s remarkable how he does not give in.”

“People who have fought against Kurt know they want him on their side when they’re fighting for the same thing,” city council member McOsker says.

Bill Doak is a managing director at Stockdale Capital Partners, which owns a hotel unionized by Unite Here. “I’ve never yelled at somebody louder and longer than I have at Kurt,” Doak says. “And we’re friends.”

He adds, “The key to working with Kurt is understanding that he truly believes from the bottom of his heart and in his mind that he’s doing good.”

Doak says the pay increase Unite Here is demanding is steep, but he acknowledges that, given how expensive it is to live and commute to work in LA, the raise aligns with the cost of living.

In the early weeks of the strike, just a handful of hotels — Stockdale Capital’s among them — agreed to sign the contract. Now, the announcements of hotels signing are coming more frequently. By February, 34 hotels had agreed to the contract. The remainder appeared poised to sign.

“The contract that we’re winning is breathtaking,” Kurt said. “It is transformative. It’s the biggest contract victory, I would argue, of any union in the last 30 years.”

Whenever the union wins a new contract, members hold massive celebrations. They post joyful scenes on social media. Kurt isn’t declaring victory yet, but he feels it’s close. Those celebrations remind him of his first big win three decades ago up north in Washington. He recently returned to the Yakima Valley and saw many old colleagues.

“I saw that they walked taller,” he says. “They owned their own houses. They sent their kids to college. You can see that they’re leaders. They’re just different people now who have continued to grow. And that to me is what these fights are all about.”

Sean Callahan is content director at Innovid and lives in Chicago with his wife, Nancy Joyce Callahan ‘87.