Left to loosen, right to tighten. “Say it — out loud — every single time,” I reminded my now very careful self. Turning this nut — on the valve sealing the flimsy plastic bag that was draining bile from Blake’s liver — the wrong way, or forgetting to tighten it correctly, meant things far worse than a mere stripped screw. This was life and death. Not something I was accustomed to even thinking about — death — let alone preparing for.

That system attached to my estranged ex-husband’s body was a single paragraph in his pancreatic cancer treatment — but a significant chapter in the rupture of our 33-year marriage, and how I came to be there, anyhow, tending to him in Florida.

After divorce, relocations and eight years of no communication, I had learned from our son that his father was dying. Instinctively, I picked up the phone. And even if Blake didn’t answer — again — I’d leave a message to let him know I’d heard. But this time, I would tell him what I felt, that if he needed anything, if this time he did not as usual “have everything in control,” I would come. And I would come, even if he didn’t.

He picked up. It was his voice, not the answering machine. “Babe,” he said without missing a beat, as if I’d just been at the grocery. I stuttered, my planned speech gone, and then our years of conflict dissolved. Our years together began to resurface. Whatever was left, was good. We talked. And talked.

“Are you seeing anyone?” he asked eventually.

“No.” What a question. But what the hell. “I tried Match for a bit, but found I was a “one lunch wonder.” For the first time, I returned the favor. “How about you?”

“No, not me. Too much heavy lifting.” I doubted that was accurate but found I didn’t care about that anymore.

We switched to the boys’ lives: one’s recent graduation and life in California, the other’s two gorgeous daughters.

“I do get out to visit the beach in winter,” I offered.

“That’s nice. But I don’t have to go far for the beach,” he said. I heard his sassy grin through the phone.

“Do you have any help?” I asked, getting down to business.

“Neighbor guy drives me to the VA in Bradenton every week.”

“Your ever-dutiful firstborn told me he wants to come down to be with you. I bought him a ticket.”

“Why? What about his family? He can’t just leave them.” Ever the orchestrator.

“You’re his family.” And with that, I realized Blake was my family, too.

So, after the call, I took the first flight out of Boise, on the reddest of redeyes, leaving everything behind — my house, calendar, winter clothes, emotions — for how long, I didn’t know.

The warmth and sodden humidity of Florida stuck the Idaho turtleneck to my back; the featureless terrain also a sharp contrast to the snowy mountains I’d just left. I drove the rental car 30-some miles on perfectly straight highways through flat but lush jungle that looked as if, given half a chance, it would reclaim the wilds that humans had carved and drained.

When I found Blake’s street among others with faux Italianate names, I gaped. The rows of beige mini-mansions evoked our family home back in Portland, from which he’d fled, except for rows of palms and the yards full of hot pink bougainvillea and scarlet hibiscus. I drove slowly into this twilight zone. What else from our old life might have been transplanted? I slipped into old habits. Why had I come? I fought back a familiar urge to run. Not this time. Go in. You’ve come this far.

I clenched my fists, exhausted but committed, climbed the veranda and rang the bell. A tidy man — butler? valet? chauffeur? — opened the door. “Um, is this Blake Healy’s?” I asked. The door swung wider and Butler stepped back. Across a length of white tile floors, I saw Blake. He looked up, found me over his readers and dropped a sheaf of papers. I, too, took him in. Yellow swim shorts, pale blue polo shirt and white indoor sandals didn’t spell “hospice” to me.

Cancer is disarming. The chemo had taken his hair but not his smile. His full-body hug at the kitchen table (where his attorney, not butler, had been finishing legal documents) melted years of rancor with his unexpected — no, shocking — welcome: “It’s all water under the bridge.”

Really? Just like that? How like him to preempt any discord. But I put his perceived manipulation behind my real concerns about his well-being.

He was thinner, even a bit taller than I recalled. Not gaunt from chemo, just more fit. From the pool, I surmised, glancing at that luscious water winking at me a few feet from the kitchen.

I, too, was different. Thinner from not self-medicating with food and wine, and stronger from doing life on my own for nearly a decade. Contrary to all expectations, our coming together was not a clash but a chord.

It’s true — I was conflicted at first. Seeing my china, bedside lamp, sofa and hand-knit afghan in another person’s house was surreal enough. But now I was suddenly “in charge.” Not only of Blake’s decline and estate, but of the detritus of his legacy. Over the years of our marriage, his control of everything in my life, from finances and friends down to the color of my clothing and the bathroom tile, had effectively eroded my confidence to make the simplest decisions. But paradoxically, Blake had chosen me to handle his life. If I hadn’t decided — on my own — to come to Florida, would I just have been informed, after his death, by registered mail? Second-guessing was of no use. He apparently trusted me; I would not let his surprise undermine this mission now.

Emboldened by this realization, I found I was a new person in our relationship. In place of reluctance, I engaged. The crater between our separate lives began to fill in.

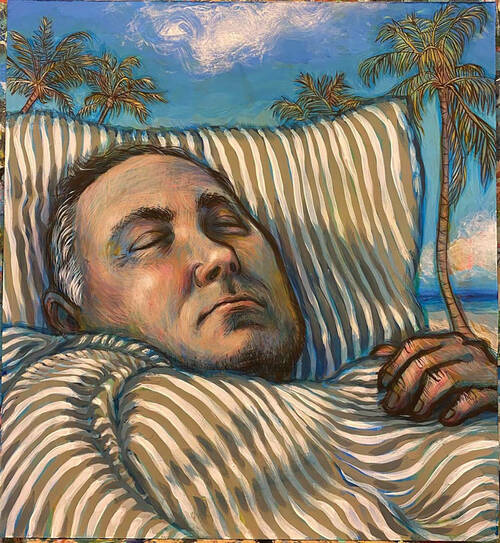

I soon began to relish the familiar roles of cook, confidant and storyteller, each seamlessly resumed. Each so long gone but rightly not forgotten. Each brought color to his face, now tan and smoothed of tensions. We had over a month together to talk by the pool — I stretched every inch in the sun, he tucked under the balcony’s shade.

As the days passed, I began to understand pieces of his life there. Among the books in his den were dozens of pocket watches he’d collected, each in its own glass dome. A Steinway baby grand piano filled half the living room. Tommy Bahama shirts had replaced Oregon’s nylon leisure suits. A Breville juicer stood on the counter where once a Mr. Coffee would have been. More to the point, I saw how Blake rallied from the pillows to converse with visiting neighbors, gossip with Joe the pool guy, await his daily time with the village priest and hear neighbor Sara play his stunning piano.

Seed radiation therapy had given way to Blake’s current, terminal state. I found it odd that radiation had replaced the chemotherapy that had worked well enough for a year. Well enough to allow Blake a semblance of his normal life, including trips from his solo retirement villa to visit the kids. Well enough for games of Go Fish with the little neighbor girls. Well enough to trim shrubs, and then, goggle-eyed, poison various predators on his Meyer lemon tree.

That was before the teeth-chattering chills, projectile vomit and struggle to remain human took center stage, including my introduction to the bile drain, which I was now responsible for emptying.

I had been instructed by him frequently enough to understand the steps and the routine. I still worried about spilling the dreadful yellow liquid on his sage sheets, biscuit wool carpet and snow-white bathroom tile. I wanted to avoid his predictable reaction to “such lack of care.”

My fingers probed the small hole in Blake’s side where the life-sustaining tubing siphoned off his bile. As it slid back and forth in the tiny angry hole, I watched with fascination, not knowing where it went or how it did its vital job of removing the citron fluid from his body.

And soon enough, the drain failed, on its own. Underlying the moments of routine and quiet health care was quicksand. Then came the doctor’s verdict: There would be no healing of Blake’s body. The drainage system could no longer keep up with the liver’s production. Blake’s biological systems would be overwhelmed in time. One by one, day by day.

And so they were. His eyes became jaundiced. Where two helpings of potato soup had been lustily consumed, now only sips of broth were tolerated. Big glasses of orange juice gave way to three ice chips. Then, the final collapse at bedside, when he was unable to lift himself, or be lifted by me, back to bed. We lay together on the floor, waiting for a posse of strong backs to arrive.

Blake was cogent, alert, and I dissolved. “What are you crying for now?” he chided me.

“Because I don’t want you to go yet.”

We both knew the fall signaled the end, but we held on to each other — and to wanting to believe that death was not now imminent.

He was not able to move from the bed again.

I brushed his teeth, changed him, read the sports pages aloud each afternoon — even though he thought Tampa Bay was still an expansion team — and emptied that damn bag twice a day. Hours, days passed. Time was marked by sunlight and lamplight. His peaceful sleep turned to rhythmic moaning. Crushed morphine rubbed on the gums of his clenched teeth did not reach his overwhelming pain. My efforts at hospice were at an end. The doctor took over with an injection, which put him at ease for a while. Blake asked him once, in one of his crowd-pleasing moods, if he was “doing a good job at dying.” The doc told him it was one of the best deaths he had ever witnessed.

Death is so final, and yet I don’t know. Witnessing it, you aren’t quite sure. I checked his pulse. On his wrist, on his neck, on his fingers. There seemed to be a movement under the skin. Slight. Momentary. Or was it? Checked again and again. Was it his pulse or mine? My lifeblood beat on while his was still. Breath? Mine or his? Minutes passed in limbo — two bodies. One life? A hope, melted to wishful thinking and, finally, to reality revealed by the ringing doorbell.

It was neighbor Sara, coming as she had for weeks, just at 7, to play Blake’s piano for him. She knew his prognosis, as did everyone on the street. I greeted her with, “Blake just died.” She replied, but I didn’t hear. I just said, “Please come play him to heaven.” She wilted with a mournful gaze, came in and played. For both of us. I recognized “Gymnopedie No. 1” coming from the distant living room. She left quietly, and the eerie chords faded.

I called the priest and the doctor, who had ministered to him daily. “He’s gone.” There had been that one grateful sigh, and he had left. That was all.

I was not sad, at least that I remember. That surprised me. It was all so ordered. His work was complete; he had made his peace. He’d left a lot undone, as I would begin to discover. But for now, the surrender of life to death was complete.

The mortuary was called. I was given a stiff Scotch. Doc and the priest were joined by a houseful of helpful, holy neighbors — the community Blake had just begun to truly appreciate — who sent me back to the room to say goodbye. Take a clip of his hair? But I’d been saying goodbye daily, hourly, quietly in words and actions for six weeks. I went to his side once again but found I had nothing more to say. I stroked what remained of his short, graying hair one more time, kissed his cheek, and said, “See you later.” No clip of hair. What was the point of that?

Valoree Dowell is a writer living in Marine on St. Croix, Minnesota, and a candidate for the Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing at the University of St. Thomas in Houston.