“All actual life is encounter.” — Martin Buber, I and Thou.

IT WAS THE ISLAND I encountered first — in January of 1985, one day after I turned 27. I had seen a movie set in Greece in high school: people in summer clothes on motorbikes, sunshine through the silver flutter of a eucalyptus. A woman I had met in college had described her time there as all languid ease and warmth. I’d envisioned lazy sun, a balmy breeze, a bungalow beside the sea, with sand and sunsets out my writing window. I’d spent three days in chilly Athens already, but I thought somehow the islands were immune to winter.

I picked the island from a hat, so to speak. I knew little about Greece, and Patmos was the first stop for the next boat leaving the harbor. A Greek man told me it was beautiful, so I decided I would write my novel there. I didn’t know that it was biblical, too — that John the Apostle had written his Revelation on its shores — but my first sight of it was of lights that seemed to hover in the night without a land below them, as if the island were celestial.

The ferry ride was nine long hours of wind and seas, but I still thought the island would be warm and magical. Magical it was, in its own way — sinuous and sloping, sheltered coves, spills of sugar-cube houses — but it was cold and hard as well, the constant wind forbidding. The romantic, the American, in me was looking for the easy paradise I’d seen on film. What I found instead was somewhere that would challenge me, humble me, declutter my life, and only then reveal its truer beauty. Patmos was paradise, yes, but not the kind I’d envisioned. Its beauty lay less in the place itself than in what happened there, in my encounters with the land and sea, with God, with myself and with the poetic man of God named Robert Lax.

The Greeks called it the Island of Love, I learned, because John also was called the Apostle of Love. You could view the three-part rock that split when he had visions, touch the place he laid his head. But it was something more that gave the land its loving aura: a belief in love that came from the loving people living there, an attitude passed down through generations. I perceived it in the people, but it was meeting Lax that made it manifest.

JUST HOW I MET ROBERT LAX is the reason I believe in miracles. Before arriving in Greece I’d been thinking about reading the autobiography of Thomas Merton, the monk who may have been the greatest Catholic writer of the 20th century. I had seen a reference to it in a book and then, while waiting for my ferry, found a copy on a bookshelf in Athens. When I’d rented an apartment on the island — not a beachside bungalow but a concrete box on a busy corner — I spent my evenings in Merton’s world. His story of a would-be writer finding his spiritual path inspired me, but it was a college friend of his, a poet named Robert Lax, who captured my attention. A Jew, he seemed to understand the Christian faith much better than Merton, and he was wiser than other people in the book. I made a note to look for him in later Merton writings.

Did I mention that the island was cold? My apartment was colder still, without a thing besides a stack of blankets to heat it. One day when I’d been typing in the frigid air for weeks and was longing for warmth, I decided to take the ferry back to Athens. The night I chose was the coldest yet, and when the ferry didn’t come I almost gave up. I heard a voice inside me, though, say to persevere, and minutes later I was boarding a boat beside an older Australian. When he learned what I was doing there, he told me many writers had come to Patmos to write. “In fact,” he said, “there’s a poet there who’s done quite well in America. His name is Robert Lax.”

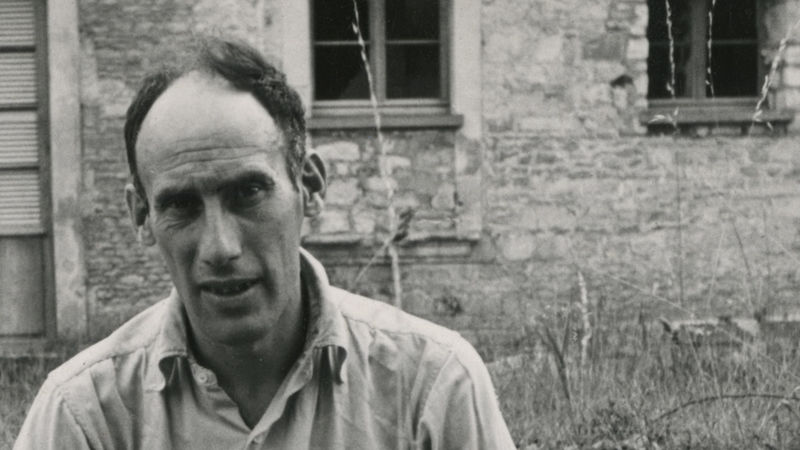

ALTHOUGH ROBERT LAX (1915-2000) was one of the most innovative American poets of the 20th century, and his life and writing inspired artists and writers as diverse as Jack Kerouac, William Maxwell, C.K. Williams and Merton himself, he has never been well-known. When he was young, it seemed he was headed for public acclaim. While studying with Merton at Columbia University in the 1930s, he edited two of its literary magazines and won every award the school offered for poetry. While still in his 20s, he published a dozen poems in The New Yorker, then worked there for a year. He went on to review movies for Time magazine, teach at two colleges, write scripts in Hollywood and edit a literary journal in Paris. But something happened along the way. Some might call it a tragedy, the way he turned his back on American ideas of ambition and success, but he saw it more as an escape. Instead of accumulating dubious things like status or fame, he found a finer way of living he would call pure act.

The origins of his pure act were jazz musician jams he and Merton watched while still in college. He noticed at these jams that the musicians were playing for themselves alone, yet their playing attained a higher level. Each one played his best, and when he did, the playing of the others rose as well. No one had to tell them when to solo or fade back. Their playing had a natural, ineffable flow.

A few years after Lax had converted to Catholicism in 1943 — drawn by a combination of his reading of Catholic books with Merton, the Church’s long intellectual tradition and his growing belief that the Jewish Messiah had already come — he met a family of circus acrobats, the Cristianis, whose way of being in the world and with each other refined his ideas. Lax had studied Saint Thomas Aquinas and valued his description of God as Pure Act. All creation, Aquinas wrote, languishes in potential, yearning toward the is-ness that is God. The acrobats’ performance, Lax thought, was as close as anything he’d seen to a fully present existence, an ability to be entirely in the moment that was both practiced and spontaneous. This ability, this nearness to the essence of God, came not only from physical ability and mental acuity but also a spiritual awareness, a fullness of love. The family was Catholic and close, trusting completely in the skill and the intention — the whole person — of each other.

Lax traveled for a while with the Cristianis, performing as a clown, but he wasn’t a circus performer, he was a writer. For years he sought a way of writing that embodied his ideals and a community that lived the kind of life he envisioned. He found the first in a simple, stripped-down, looser style he felt expressed the things his soul was saying to itself and the second on the island of Kalymnos in Greece, where an entire society of fishermen and sponge divers seemed to live a traditional and yet spontaneous life. They were Christians, too, Greek Orthodox. He settled among them to write his poems and learn their wisdom, edging closer to pure act.

IN HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY, The Seven Storey Mountain, Merton describes Lax as having a “natural, instinctive spirituality.” It was this instinctive spirituality that made Lax uncomfortable with the calculating business world he found the year he worked at The New Yorker, the same year —1941 — that he, a pacifist, was subject to the draft, the year his life and his perspective changed. Fired by The New Yorker that November, just days before Merton entered the cloistered life, Lax fled to Harlem, where the previous summer he and Merton had worked at a charity called Friendship House. There, while handing clothes out to the poor, visiting shut-ins and writing letters for people who couldn’t read, he discovered a different way to live. Embracing rather than rejecting poverty, he devoted himself to being a loving presence. When he left Harlem, he searched for years to find his true vocation before realizing that being a loving presence was a vocation itself.

When Lax moved to Greece at age 46 in 1962, after experimenting with living as a loving presence among immigrants and outcasts in dangerous Marseilles, his intention was to live and write as simply as possible. He found that the change he’d made in his poetry, from lush, lyric verse to stark, simple columns, was perfectly suited to the elemental landscape of the rocky islands. No longer concerned about his reputation as a poet, he turned his attention to recording the world around him and inside him as accurately as he could.

In time, other poets, especially in Europe, discovered Lax’s work and included it in their journals and anthologies. By the time he died at 84, Lax had published more than 25 books and 600 poems. He had done dozens of readings in Germany, England, France, Italy and the United States, too. But mainstream publishers never embraced him, and he was happy living in his island world.

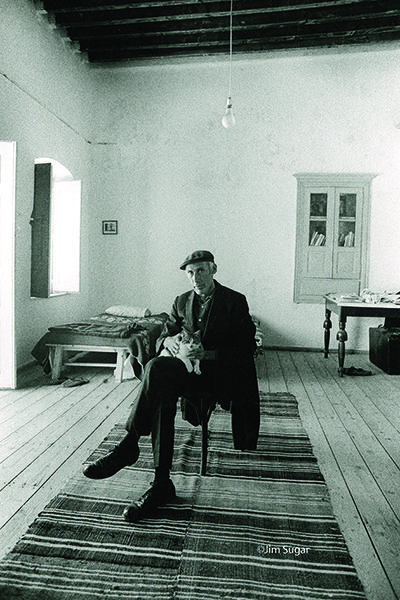

IT WAS IN THAT ISLAND WORLD I landed that winter 30 years ago. Lax had moved from Kalymnos to Patmos just five years before, when he was in his 60s. There, for the first time in his life, he had a small house of his own, purchased for him by his niece and her husband. The night we met, he invited me up the stairs and corridors that led to it. In its way, it was as simple as he was, mostly just a whitewashed room in which he slept and wrote and entertained guests. The walls were filled with postcards, children’s drawings, photographs and quotes from friends or saints or writers he admired. One that seemed especially apt came from Saint Seraphim: “Acquire the spirit of peace and a thousand souls shall be saved around you.”

We had only one week together that first time, but when I returned to the United States I took a job leading European tours. For the next decade I spent several months a year in Europe, and every year I made my way to Patmos to spend time with Lax. The visits came in different seasons. Sometimes he had just come back from one of his reading tours. Other times he’d stayed right there for months. His house was at the top end of the main town, Skala, high above the harbor and the noise. Although he was 69 when I met him, his hair and beard already white, he remained robust for years. He’d sit me down behind a long table, set a cup of tea in front of me and pull a chair up on the other side. Then we’d talk and laugh and talk some more.

Although Lax told stories easily and wasn’t afraid to impart wisdom, he didn’t force his words on you. Many times he’d simply ask a question about something he’d been thinking about, listen to your thoughts, and only then, gently, offer his own. When the conversation paused, he’d lower his head and let silence fill the room. He was comfortable with quiet, even in the presence of others. He preferred it, in fact, to idle chatter. He loved jokes because they produced laughter, but he never spoke just to fill time.

Over the 15 years I knew Lax before his death in 2000, he encouraged me as a writer and taught me to be settled in myself. “Don’t worry about making big choices,” he would say. “Make the small ones, and the big ones will take care of themselves.” Among the small choices he urged me to attend to was deciding which word to put next. He told me not to think about an editor or even an audience, except perhaps one other person. “Write for yourself,” he said. “If others have a chance to read what you’ve written, they’ll be lucky.” Perhaps the most important thing he told me was to write every day. “That way, when times get rough,” he said, “writing will be a habit.”

He never talked to me about technique, except to quote his favorite writer, James Joyce, who said to write as if sending a telegram in which every word cost a dollar. What he taught me instead was how to be a writer in the world. He showed me I could be a writer despite distractions and questions and lack of worldly success. Not just any writer, either, but a spiritual one. A person for whom faith and art are intertwined. It was on Patmos one dark night, while walking into the wind alone beneath a bright moon, that I first thought I might really be a writer, someone called by God to write.

What differentiated Lax from many Christian writers was how fully he was both an artist and a man of God. He was uncompromising as a poet, yet his loving presence was what most distinguished him, a presence nourished in the solitude he shared alone with God. He liked the title of a book he’d seen, Alone for Others, because he felt that in those private times, those hours he spent praying, meditating or writing, he was becoming someone who might know himself and God enough to offer something to others. Not instruction or advice but the wholeness of a man fully alive.

If Lax had a goal in his life and art beyond being transformed as fully as possible into a being filled with pure love, it was this one, expressed in one of his best-loved poems:

turn

ing

the

jun

gle

in

to

a

gar

den

with

out

des

troy

ing

a

sin

gle

flow

er

…

The landscape of Patmos isn’t what you picture when you hear the word garden. The terraced fields turn green in spring, but otherwise the island is a rocky outpost with a smattering of sparse brush, a bald head with a patch of hair here and there. Even so, there’s great beauty in it. Not just the beaches, which the tourists come for, or the monastery on its highest hill, which, along with Saint John’s grotto, draws a constant stream of cruise ships in summer. It’s something in the land itself, the sea around it, a solidity and peacefulness and holy feeling.

The island Lax loved most was nearby Kalymnos, where he settled in 1964 among people he saw living lives of pure act, a sacred and spontaneous society still guided by the ancient and biblical ideals. Within a decade, though, as war with Turkey loomed, many of the fishermen and sponge divers he had loved had turned against him. Peaceful as he was, he was a foreigner and some accused him of spying. With trust frayed, he moved to Patmos, where the landscape had always seemed more holy anyway. During a visit there in October 1973, just before the Turkish troubles began, he wrote:

patmos, holy patmos. i’ve never come here without the feeling, at least on the first few days, that the island is holy.

the bend of the walk around the bay. the view of the monastery up on the hill (a citadel) as seen from far end of the bay.

the terracing of the hill.

a feeling, real feeling, of peace in the air.

The next day he elaborated, focusing on rocks and peace:

a walk this afternoon out on a (familiar) high road by the sea. beautiful, volcanic rocks at roadside: apocalyptic-looking: sculptured: more by a painter (giotto — or even el greco) than by a sculptor (who’d want to make them into men, not rocks); strange majesty, strange intimacy too — they talk in a familiar voice: apocalyptic presences, (someone who wrote to me last week at kal said “those stones (in greece) really speak.” now i know what he means.)

and i felt all today as i did yesterday that peace, deep feeling of peace is here. that here is where i should stay at least for a while (& heal the nerve-ends), that here things would grow, things would speak.

Although he had been living on Patmos for only a few years when I met him, the setting —with its connection to Saint John and its loving people who loved him — seemed so perfect for him, I assumed he had always lived there, as did others, including the celebrity photographer Richard Avedon, who, for a French magazine, photographed Lax sitting in the brush on the island’s rocky ground.

ISADORA DUNCAN ONCE SAID about a dance, “If I could tell you what it meant there would be no point in dancing it.” That’s how I feel about knowing Lax. Although he said many wise things to me, some of which I copied down, it wasn’t what he said but rather who he was and how he was — in the world and with me — that mattered. He once told me there was little difference between us, and I knew what he meant. He was much wiser than me, but we were fellow travelers, learning from each other.

“Learning what?” you might ask. To watch and wait, I suppose. He suggested once that maybe all of life is training. If there’s one thing he wanted to pass on to me, it was probably the spirit of that training, the “inborn direction to the living God” Merton had noted. The last time I saw him, he told me he’d dreamed I’d reassured him that peace was a good thing to seek and love did conquer all. The dream came not from doubt, I think, but from hope that I would follow in his footsteps.

But there was something else that bound us, something I caught in a journal entry in 1992 when he was 76 and I was 34, one nearing the end of his writing life, the other getting started. “In many ways,” I wrote, “most of them quiet, Bob is more important than Merton — for me and maybe for the world today — because he combines the spiritual with the creative. Of course Merton was creative, too, but creativity was not his focus. Bob is an artist first. I don’t mean by this that his spirituality or spiritual quest comes second. What I mean is that the two are intertwined, part of the same experience, the same quest. For Bob, artistic expression is spiritual expression, and the hands that grope for God are stained with ink and oil. In these days when it’s difficult to pass on values in a traditional way, we must encode them in literature and art.”

The entry went on to cite an interview in which Lax, in answer to the interviewer’s questions about creativity and the spiritual life, said all of us are meant to be contemplatives first, not actors. If we are trained for contemplation rather than for action, he said, when the time comes to act, we’ll know what to do.

He told me once that he had been writing poetry so long, writing was like breathing. He told me, too, that when he read his poems out loud, the audience would breathe together. If I have taken anything from him, I hope it’s his kind of breath. His way of breathing.

Michael N. McGregor is a professor of English and creative writing at Portland State University and the author of many essays, articles, short stories and poems. In 2015 Fordham University Press published his book Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax.