Unless something unexpected or cataclysmic happens, American voters will face the prospect — like it or not — of choosing between President Joe Biden and former president Donald Trump in the 2024 battle for the White House.

The United States has never had an Election Day that pitted an 81-year-old (Biden) against a 78-year-old (Trump) for the presidency. But does history offer any clues to suggest what might occur next November 5?

Biden is not only running for reelection with the weight of his age and low approval ratings on his back. He also will be trying to do something that hasn’t been accomplished since the early days of the nation.

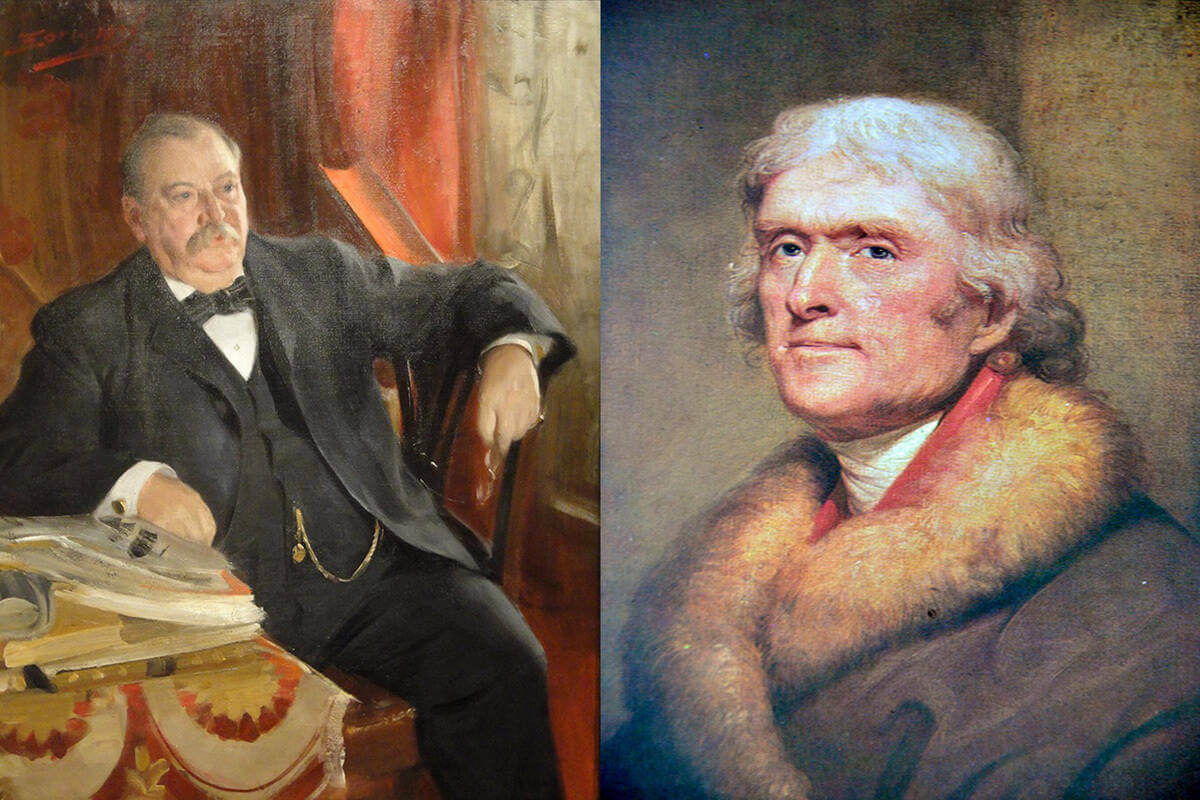

No president who previously served as vice president has completed two full terms since Thomas Jefferson, the third chief executive who occupied the White House between 1801 and 1809. Since then, former veeps have confronted problem after problem either in attempting to win the highest office or staying in power.

Besides Jefferson, the only other ex-No. 2 who prevailed twice at the ballot box in presidential contests was Richard Nixon, victorious in 1968 and 1972. He, however, resigned in 1974 as a result of the myriad revelations known to history under ignominious umbrella term of the “Watergate scandal.”

Fifteen former vice presidents have become president, eight because of death or assassination. Ten of those 15 subsequently won White House elections on their own, but difficulties of one kind or another kept dogging them.

In the 20th century, Theodore Roosevelt (TR), Calvin Coolidge, Harry Truman and Lyndon Johnson all won four-year terms in their own right after succeeding, respectively, William McKinley, Warren Harding, Franklin Roosevelt (FDR) and John Kennedy. (McKinley and Kennedy were assassinated, while Harding and FDR died of natural causes.)

Interestingly, the quartet of TR, Coolidge, Truman and Johnson — two Republicans and two Democrats — decided not to seek a second full term after winning their first presidential elections. Truman in 1952 and Johnson in 1968 suffered from widespread public opprobrium and, frankly, worried about losing.

In TR’s case, he stepped aside for William Howard Taft in 1908 but became unhappy with Taft’s White House performance. In 1912, Roosevelt mounted his third-party “Bull Moose” campaign, receiving far more votes than Taft yet finishing second to Woodrow Wilson.

If you take the long view, the 20th century wasn’t particularly kind to sitting or former vice presidents. Five were defeated either pursuing the White House or trying to continue as president: Hubert Humphrey, Gerald Ford, Walter Mondale, George H.W. Bush and Al Gore. In addition, Henry Wallace, FDR’s second (of three) vice presidents, launched a third-party attempt against Truman (FDR’s third VP) in 1948 but received less than 10 percent of the vote.

Biden, who was Barack Obama’s understudy from 2009 until 2017, can take some consolation that he overcame a huge historical hurdle in 2020. He became the first Democratic Party vice president without previous service in the highest office — like Truman or Johnson — to win the White House since Martin Van Buren in 1836. However, Van Buren, popularly known by his nickname as the “Little Magician,” couldn’t perform the necessary trick to be reelected in 1840.

On the Republican side, Trump, who’s dealing with the burden of several court cases and 91 felony counts against him, will be trying to follow in the footsteps of Grover Cleveland, a Democrat and former governor of New York. Near the end of the 19th century, Cleveland ran in three successive elections.

He was victorious in 1884, lost in 1888 and came back to win in 1892. In ’88, Benjamin Harrison defeated the incumbent Cleveland, but four years later the former president returned to the White House, making Harrison an ex-commander-in-chief.

What’s different in Trump’s elections as opposed to those of Cleveland is that Trump didn’t win the popular vote in either 2016 (behind by almost three million ballots to Hillary Clinton) or 2020 (over seven million short of Biden’s total). Cleveland obtained the most votes cast three consecutive times, a feat one shy of FDR’s string of four triumphs in 1932, 1936, 1940 and 1944.

As happened in 1892, with Harrison versus Cleveland, the 2024 race will see the occupant of the White House confronting the challenge of a previous resident of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. If it’s any comfort to Trump, Cleveland’s third attempt proved to be his strongest in both popular votes total and in Electoral College dominance.

History is at best an imperfect yardstick in trying to take the measure of a future election or anything else. Very different times and very different circumstances determine what will happen at a given period, even though the past can shed some light on the path to the present.

Will Biden be the new Jefferson? Will Trump match Cleveland?

In today’s starkly divided America, with political views poised on a razor’s edge, arriving at answers to those questions will be far from easy. The one granite-strength certainty for 2024 is that making electoral predictions is not only a pointless exercise but also a fool’s errand.

Bob Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Professor Emeritus of American Studies and Journalism at Notre Dame. He’s the author of several books, including the forthcoming Mr. Churchill in the White House: The Untold Story of a Prime Minister and Two Presidents and The Glory and the Burden: The American Presidency from the New Deal to the Present.