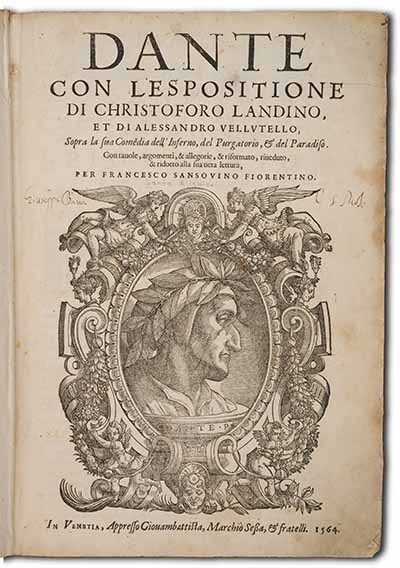

In the first years of the 20th century — in between facing censure from the Catholic Church for a book favorable to the theory of evolution and planning Theodore Roosevelt’s ill-fated expedition through South America — Father John Zahm, CSC, traveled around Italy, buying as many volumes as he could find on Dante Alighieri for Notre Dame’s collections.

Zahm, the Holy Cross Provincial at the time, had wide latitude to shape Notre Dame as he saw fit. His vision, which was to build a great Catholic research university, had Dante front and center. He acquired more than 3,000 volumes.

“The study of Dante would have to be central to the curriculum,” Christian Moevs, Notre Dame associate professor of Italian, told me, “because Dante is the culmination of the great focal points, the most sublime and profound expressions of Catholic, Christian spirituality.”

Zahm was removed as provincial in 1906 under accusations of financial mismanagement. He continued to travel, and he wrote books on women in science and religion before his death in 1921. But his Dante collection, said Theodore J. Cachey Jr., Notre Dame’s Ravarino Family Director of Dante and Italian Studies, went underused and underappreciated for 70 years.

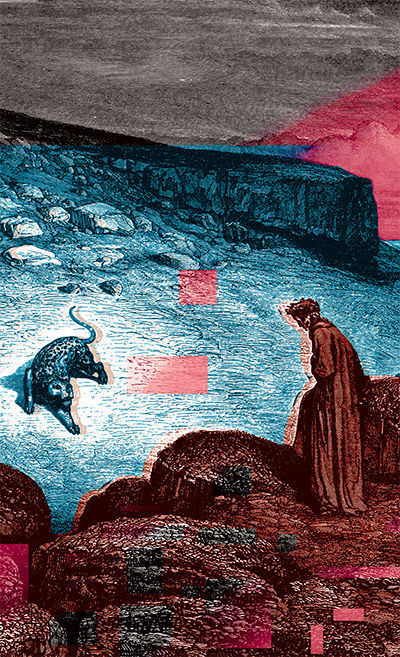

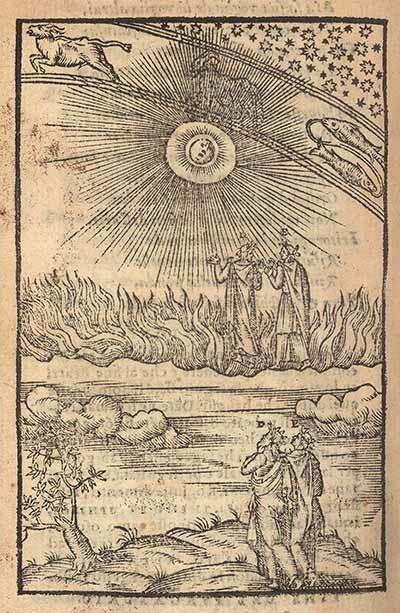

Dante was, of course, taught at Notre Dame during those decades. His Divine Comedy is one of the seminal works of Western literature, and this journey through hell, purgatory and heaven is largely responsible for how we envision the afterlife today. Dante’s sweeping works incorporated philosophy, religion and human nature, and his Italian shaped the language itself.

“He essentially was trying to encompass everything that was accessible to him,” Moevs said, “and absorb it in one overarching, comprehensive vision of reality and the world, nature, everything.”

Dante is also part of the American literary tradition, Cachey pointed out: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow translated the Comedy and founded the Dante Society of America, along with James Russell Lowell and Charles Eliot Norton. There’s even a historical thriller, The Dante Club, which reimagines those literary greats translating Dante while running around Boston trying to catch a serial killer.

So, to Cachey, Notre Dame was sitting on a 3,000-book gold mine.

“We felt [the collection] needed to be valorized and enhanced and restarted, really,” said the academic director of Notre Dame’s Rome Global Gateway via Skype. “So one of the first goals of the founding of the Dante program was to revive the rare book collection of Dante studies in the Hesburgh Library.”

That happened in 1995 with a million-dollar endowment establishing the William and Katherine Devers Program in Dante Studies. Cachey has been the program’s director ever since.

The Devers program quickly made waves with its seminars, conferences and lectures involving scholars from around the world. It has collaborated on events with schools such as the universities of Cambridge and Leeds, published a book series and sponsored special projects, including an investigation into how Dante acquired his knowledge.

As a result, over the past two decades Notre Dame has become a leader in Dante studies, a hub with several world-class scholars on the faculty and resources on subjects that reflect Notre Dame’s Catholic focus: theology, philosophy, history, medieval studies and Italian. The program draws top Dante students, too: Last year the Dante Society of America’s top undergraduate and graduate essay awards went to Notre Dame students.

Such a concentration of talent attracted Zygmunt Baranski, a longtime Cambridge professor and a leading authority on Dante. Baranski was a visiting professor at Notre Dame several times before joining the faculty in 2011 as professor of Dante and Italian Studies.

“I wanted to spend part of my career and do my research in such an intellectually supportive environment,” he said. “To me, that was very important when I came here. It’s very rare to have that level of commitment to humanities, to the Middle Ages, to Dante.”

For Moevs, that environment inspires productive interaction with other scholars that has been crucial to shaping his ideas. Moevs is interested in Dante’s views on philosophy, theology and metaphysics — relatively rare topics in a field largely focused on linguistics, poetics and politics. He is working on a series of essays about the Catholic mystical tradition in Dante’s Paradiso, a project influenced by his colleague Vittorio Montemaggi, an associate professor of religion and literature who studies the interconnection between Dante’s poetry and theology.

When you work with someone, says Moevs, “your own thinking becomes more refined, more subtle. That, I think is the key thing. We’re always looking for profundity, precision, subtlety in what we do, asking questions that are ever deeper, ever more precise and ever more rewarding in the kind of understanding they bring — and that, you can’t do it alone. Human minds are interconnected.”

Prior to joining the Notre Dame faculty in 2009, Montemaggi contributed an essay to a Devers-published book and spoke, at Moevs’ invitation, at a conference on Dante’s theology. Montemaggi’s work, Moevs said, “has had a very significant impact on the American work and interest in the field.”

This wide-ranging scholarship is shared both with the graduate students who come to Notre Dame specifically to study Dante and the undergraduates who, like me, stumble into the field. I took Cachey’s seminar on the Inferno my freshman year. I didn’t become a Dante scholar — I’m more interested in Cold War history than medieval poetry — but I became fascinated by the history and commentary tradition and took three years of Italian as a result.

This year, I took Baranski’s course on the Divine Comedy and dove back into 13th-century Florentine politics, the role of Virgil, the symbolism of fire and water, the overriding importance of revelation. Baranski, like Moevs and Montemaggi, believes the Divine Comedy is trying to explain complex theological ideas as well as God’s role in the lives of ordinary people — but he encouraged us to speak up if we disagreed, to grapple with Dante’s ideas ourselves.

For Montemaggi that wrestling goes back into scholarly research. He recently published a book on the importance of encounters in the Divine Comedy — he thinks the Comedy and its arguments build primarily through the narrator’s interactions with people in the afterlife. Understanding the significance of human encounter, he told me, emerged through teaching Dante.

Moevs said he’s seen the significance of studying Dante impact the lives of students long after they’ve closed their last book.

“You get the feeling that Dante lingers with them, and it’s an important moment, because it’s a way of thinking seriously about their own lives and about their own experience, about the whole world, and trying to come up with a picture on their own, a way of their own, in response to Dante, to make sense of everything,” Moevs said. “You know — where am I going? Why am I here? Dante makes you ask those questions and presents an extraordinary model of how one could go about answering questions like that, this probing into the mystery of our own existence. They get really inspired by that and that’s something that goes on for a lifetime.”

Emily McConville, a history and Italian studies student at Notre Dame, is this year’s Hannah Storm Journalism Intern.