Andrew Fedynsky ’69 was born in 1947 in Innsbruck, Austria, where his Ukrainian refugee parents were living in a post-World War II displaced-persons camp. Eight months later, the family immigrated to the United States and eventually settled in Cleveland.

His father was an early leader of the Ukrainian Museum-Archives that had opened in Cleveland, and in time he became its director. The younger Fedynsky worked for years in Washington, D.C., for Kansas Senator Bob Dole and later for Representative Mary Rose Oakar, whose district represented part of the Cleveland area. More than 30 years ago, he started working full time at the Museum-Archives, succeeding his late father as director.

Fedynsky and his wife, Christine, have two children, Michael ’12 and Alexa ’17.

How did the Ukrainian Museum-Archives come to be in Cleveland?

In 1952, when Leonid Bachynsky founded the Ukrainian Museum-Archives, Cleveland had a vibrant Ukrainian community going back to the late 19th century, when many immigrants settled in the Tremont neighborhood overlooking the industrial valley. The established Ukrainian diaspora helped a post-World War II wave of political refugees, including Leonid, adjust to America.

A scholar and educator in Ukraine, Leonid got a job as a machinist and then in the evening and on weekends, reverted to being a scholar. An inveterate collector, he brought his treasures — along with worldwide connections to similarly displaced scholars and diplomats — to Cleveland, where he was able to tap into longstanding social, economic and cultural resources to develop his museum. From very modest beginnings, it’s grown three generations later into what we have today.

What does the collection include?

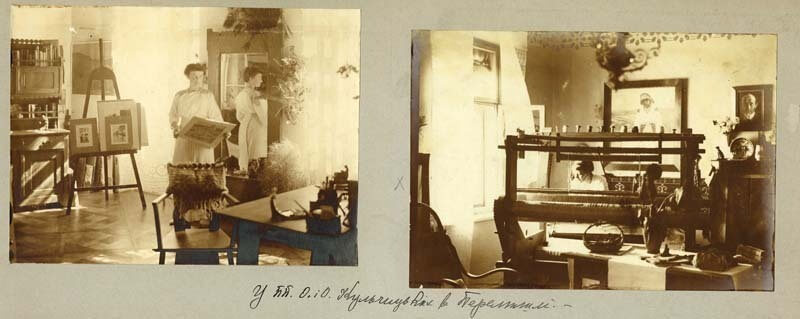

The UMA has a very large collection of books and periodicals, many more than a century old, along with folk art — such as pysanky [decorated Easter eggs], embroidery and ceramics—posters, photographs, maps, postage stamps and currency, fine art and ephemera, all documenting various dimensions of Ukrainian culture and history. The UMA continues to accept donations of valuable materials and has a growing staff of volunteers and professionals.

The library has . . . thousands of discrete newspaper and magazine titles. Some of those titles consist of a single issue; some are 50-, 60-year runs. We partnered with the [United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.] on publications from post-World War II displaced persons camps, [such as] where my parents were in Austria. And we digitized 75,000 pages.

Is the collection still growing?

People continue to bring their treasures. We often hear, “Grandma passed away. We can’t throw away her library, but we don’t read this stuff anymore. Do you want it?” And of course, we take it. That’s how we ended up with this huge collection.

What additional preservation steps have you taken since the 2022 Russian invasion?

We separate what’s new to our collection from duplicates. Duplicates we preserve because Russia has destroyed hundreds of libraries — whether they’re municipal libraries or university libraries. We are working with our partner institutions to eventually send these duplicate publications to Ukraine.

And we’re working with our members of Congress as well to have the resources — when Ukraine needs to rebuild — to share what we have: either digitally or physically putting them in boxes and shipping them.

Has public interest in the museum increased since the war began?

Yes. We’re in demand, particularly now given the global situation revolving around Ukraine.

Why did you attend Notre Dame?

I decided to apply in 1965 because of the sophomore-year Innsbruck program in the city where I was born. Notre Dame has been a blessing ever since. I’ve spent a good deal of my post-graduate career combining work in the broader community with Ukrainian activism.

How many times have you visited Ukraine?

I’ve been to Ukraine 10 times, starting with the summer of 1970.

What does the collection mean to you personally?

I’ve always been sort of a mystical person. My parents had a difficult life, with the war and immigration. They came to America with two suitcases, barely spoke the language, and they ended up sending three sons to college.

My dad passed away. He was all of 66. And then my mom passed away four years later. I knew that the [museum] building with all these treasures was pretty much abandoned. There was just one elderly man who lived there as a caretaker. I started dreaming about the museum. And I took that as a sign from God.

What has inspired your life’s work?

I’ve dedicated my life to preserving Ukrainian cultural artifacts, one of the largest collections in North America. These objects tell the story of the ongoing fight for Ukraine’s independence, freedom and democracy. They communicate about daily lives over the course of generations of a people in their own country and around the world. It’s a story Vladimir Putin wants to erase.

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine.