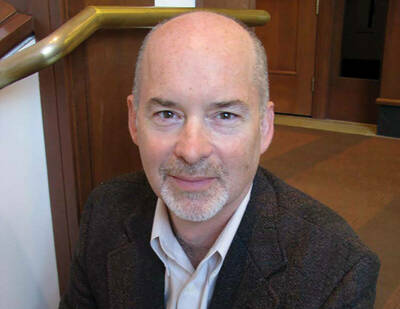

John Wigger grew up in the air, sitting beside his father in a one-engine Cessna. Later in his own aerobatic plane, Wigger flew loops and spins. Today, as a professor of history at the University of Missouri, he teaches down-to-earth courses on the social and cultural history of the United States.

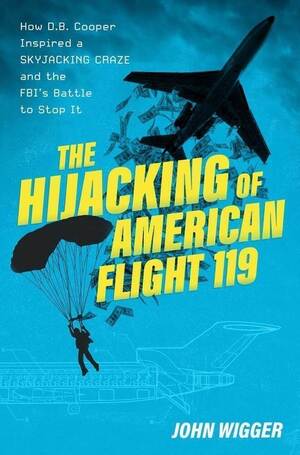

Wigger ’90M.A., ’94Ph.D., soars again in his 2023 book, The Hijacking of American Flight 119: How D.B. Cooper Inspired a Skyjacking Craze and the FBI’s Battle to Stop It. He documents a lawless period in U.S. commercial aviation: Between 1968 and 1972, hijackers commandeered 141 jets, something unthinkable in the era of high-security travel.

Air pirates during those years diverted 92 commercial aircraft from the U.S. to Cuba. What accounted for this crime spree?

Few of these “Take me to Havana” hijackings were overtly political. The Cuban hijackers were homesick and couldn’t figure out another way to get back. Some Black Panthers thought Cuba would help them with their revolution. Other [hijackers] were mentally disturbed. Career criminals thought getting to Cuba would be better than staying in the U.S. and going to prison.

The Cuban government treated passengers well. It put them at the best hotels and took them to nightclubs or the beach. Passengers came back and said it was like an unintended vacation. There were stories of people who booked flights through Miami hoping to get hijacked so they could spend a day or two in Havana.

No passengers died or were injured. The risk seemed low. It seemed to some people like a free adventure. Things ended much differently for hijackers. Almost all ended up in harsh Cuban prisons.

Other hijackers were in it for the money.

They didn’t want to go to Cuba, because they wouldn’t get to keep the money there. Their problem was, how do you escape once you’ve got the money? That’s where D.B. Cooper comes in. He’s figured out how to get away.

You’re referring to the first parachute hijacker, in 1971. Neither his body nor the $200,000 he demanded were found. What do you think happened to him?

If Cooper had simply hit the ground and died, by now someone would’ve found him.

Five other hijackers after him jumped from 727s and survived without serious injury, so I don’t see why Cooper wouldn’t have as well.

He knew planes. He wanted the wheels down and the flaps at 15 degrees. He wanted the back door left open and knew that could be done on a 727. How much he knew about parachuting is difficult to tell.

A number of hijackers were Vietnam and World War II vets who had PTSD. Cooper was probably one of those guys.

He’s famous because we don’t know who he was. All the other jumpers were caught. In that sense, he can be whoever you want him to be. Until he’s identified, that makes for a compelling mystery.

What was airport security like back then?

My 18-to-22-year-old students are fascinated there was a world where you could buy a plane ticket with cash, without showing ID, and walk straight to the plane. No one checked what you carried. You could be anonymous. There was nothing like the TSA. Each airline ran its own security.

What’s more, flying before deregulation in the late 1970s was expensive. People dressed up to fly. They wore suits. The assumption was, this is for people of means, for business travelers, and this is not an environment where you’re going to find dangerous people.

There were days when multiple hijackings happened. My students can hardly imagine a world where this could happen nonstop around the clock for the better part of five years.

What brought this era to an end?

Hijackings turned more violent in 1972. A few passengers died. Southern Airways Flight 49 was a horrific experience for everyone on board. Three hijackers threatened to crash a DC-9 into the massive uranium enrichment plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

After 1972, increased security meant metal detectors and X-ray machines for baggage. There were 33 hijackings that year, but in 1973 the only one attempted failed. People said, “Well, we’ve solved this problem. We’re keeping weapons off planes.” Of course, 9/11 proved that wasn’t true.

You write that stewardesses, as flight attendants were called, were unsung heroes.

Because pilots are in the cockpit, they usually didn’t have much contact with hijackers. Stewardesses did. They were almost all in their early-to-mid-20s. Without exception they handled situations phenomenally well. They de-escalated tension. They created rapport with hijackers. They negotiated with them. In every situation I came across, they were the ones who managed these hijackings to peaceful endings.

You write that we’ll soon enter an age of decentralized air-taxi travel that will pose new security concerns.

We now have a model where big commercial jets fly from of a limited number of airports. If things that look like giant drones carry fewer people and land at smaller fields, that will change the nature of airport security. I don’t think we’ve envisioned a way to scale security for those settings.

Interview by George Spencer, a freelance writer who lives in Hillsborough, North Carolina.