Photo by Barbara Johnston

Photo by Barbara Johnston

The obituary didn’t say much.

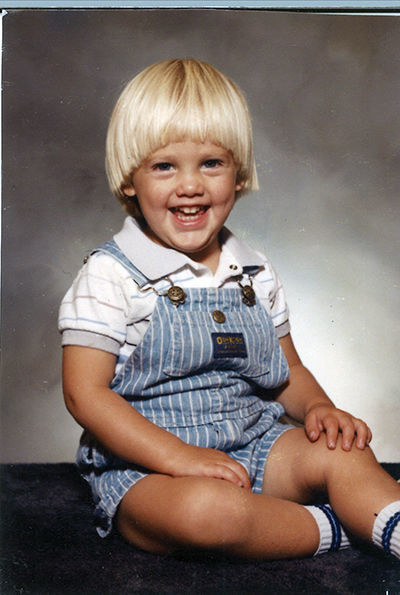

Brian R. Fenzl died in Boynton Beach, Florida. He’d been a resident of Delray Beach; he was formerly of Wooster, Ohio. He died March 30, 2011. He was 27. Survived by his parents, Thomas C. and Joan Barry Fenzl, still living in Wooster. And an older brother named Thomas, an older sister named Kimberly Ann.

The obituary said he had worked in food service, was a barista. It said he enjoyed biking, snowboarding, the outdoors, organic farming and spending time with his family. He was a member of St. Mary Catholic Church. It didn’t say much else. There was a Mass of Christian Burial, but no visitation.

The obituary didn’t say housekeeping needed to get into the room. That a motel worker found the body. That Brian Fenzl had overdosed on heroin.

There was no retelling of childhood’s sweet and treasured moments, any recounting of good times, any elaboration on a life that — like any life — slips the grasp of a newspaper death notice. The obituary didn’t say how he got to this point, what had led him here, how his days had been a careening odyssey of highlights and heartbreak, leaving his parents, still nine years after his death, trying to assemble a coherent narrative from fragments of memory. A tumultuous lifetime of flight and fall, rehab and addiction, impossible to put into words.

Talking helps. The recorder is on. But there is still no happy ending.

Joan and Tom Fenzl ’74 will tell you Brian was a difficult child — “like that girl in the poem,” his mother says. “When he was good, he was really good. When he was bad, he was . . .” Her voice trails off. “He kind of had two lives,” says Tom. “Brian had so many faces,” says Joan.

In elementary school Brian was “extremely intelligent” and “extremely personable,” says Joan, earning praise from teachers for helping others, even reaching out to younger kids. She remembers the time Brian handed their carryout pizza to the street person begging. When she asked him what he was doing, he told her the man needed the pizza more than they did. “Of course, I felt like this big.” Lodged in her memory are calls from mothers and counselors just wanting her to know how Brian had gone out of his way to help others struggling with addiction.

Like any parents, Joan and Tom have sifted through the pieces, looking for the first clues of trouble, trying to fathom where it went wrong, what they should have done, wishing they knew then what they know now. Brian had a temper, he acted out, threw tantrums. “He was sensitive,” says Tom. “He loved animals, and any time he saw any kind of animal . . . well, do you remember the time the cat got a rabbit?”

“He was just beside himself,” says Joan. “I remember a time when he was complaining about a teacher, and he’d say how his teacher wasn’t fair, and Kim looked at him and said, ‘You expect Mr. Bell to be fair?’ Yes, he did. He expected everything to be fair and, when it wasn’t, he just had a hard time accepting it. He had these ideals in his head and, when things didn’t come together like he thought they should, he had a really difficult time accepting life on life’s terms.”

Sixth grade was OK, they agree. Seventh grade? Well, what about that night he threatened to kill himself? No, that wasn’t till eighth grade. They had been to a psychologist by then. Because they’d been meeting with the school nurse. Perhaps, counselors suggested, his behaviors may indicate some form of depression; psychological anomalies do often manifest themselves in adolescence, the teen years. Brian was 13.

Yet mood changes and new behaviors are part of adolescence. Most assume it’s a phase that will pass, part of growing up, and not the initial warning signs of personal demons haunting. “We were just a typical family bringing up kids,” says Joan. “We took the kids to church. We had dinner together every night, did all the things they say you should do. . . . I don’t know. We just didn’t see it coming.”

“I know they talk about transitions,” says Tom, “that the time between elementary school and junior high is tough, the kids, the age and whatnot.” It was a new school; there were new friends, new friends in a rougher neighborhood. “But something fundamentally changed,” he says. “It wasn’t till later that we realized what it was, and we were really blind to it.”

“Denial,” says Joan.

“Or ignorant,” says Tom. And counselors? “They would tell us Brian’s just a normal kid and doesn’t have any problems.”

Still, there was that night when Tom and Joan wouldn’t let Brian go to a rock concert. “He just got angry and went to the basement and threatened to cut himself.”

Brian got mad when things didn’t go his way, got enraged when confronted about his behavior. The Fenzls sought more help. Then that time he was admitted to a nearby hospital, and kept there several days. They said he was maybe bipolar. He started on lithium. He “became more reclusive,” says Tom. “He just kind of hung out in the basement, stopped taking care of himself, started getting heavy . . . was refusing to go to school.”

“We just couldn’t control him anymore,” says Joan. They suspected mental problems. “When we thought it was a mental illness,” says Joan, “of course we were going to do everything we could to get past that.”

“I thought we were doing what was right,” says Tom.

It was then Brian told his father, ‘Dad, if you don’t get me out of here, I’m going to become a heroin addict.’

“We didn’t know what we were dealing with,” says Joan. “That’s the bottom line. He didn’t want us to know.”

Tom explains: “When he could not tolerate going to school in our hometown, we took him to a school with kids that were having problems.” A boarding school in Maine. “They saw Brian for two minutes,” says Tom, “and knew it was drugs. I was just dumbfounded. We were so in the dark about it all, yet these people that were complete strangers, who’d obviously dealt with it all the time . . . I mean, they knew right away exactly what it was and started talking about what concerts he went to and all this other stuff.”

During intake, the Fenzls learned Brian had started drinking in junior high, smoked weed, and would go to concerts where “he’d get pills and mushrooms and all kinds of stuff.”

Says Joan: “Psychiatrists and psychologists are not very good with addicts or alcoholics because addicts and alcoholics will, to the best of their ability, tell you what they want you to hear — so they can protect their addiction. He was smart enough at age 13 to pull the wool over their eyes. Not one of them ever said to us, ‘I think your son has a problem with drugs and alcohol.’” He was fine letting people think he suffered depression; that hid his drug and alcohol use.

“People who are drug addicts and alcoholics do it to get relief from the pain of what’s going on in their lives,” she says.

“I don’t really know what his unhappiness was,” says Tom, “what he was unhappy about, specifically.”

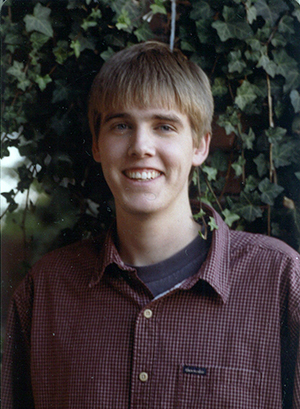

Brian spent the next two years in Maine. Responded well to the discipline and regimentation. “Bought into the system,” says Tom, “lost weight, did well at school.” School administrators said he was ready to leave, says Joan, but they never dealt with Brian’s personal issues. “Abstinence does not solve the problem,” she says.

“We thought, ‘Oh my gosh, Brian’s back. We’re so happy. He looks happy. He looks like himself again,” says Tom. “But he didn’t really develop any skills to handle it. As soon as we brought him back to Wooster, whatever his demons were, whatever it was, he just fell back into the same patterns and same bad mistakes. It just spiraled out of control again — worse, though, because now he’s that much older, getting into that much more stuff.”

The afternoon sun has shifted, and the talk turns from a retrieval of memories to reflection. “The other thing that I know now that I didn’t learn until very late,” says Tom, “is that it is a family problem, and because we never got any information or help or direction as to what we could do as a family to help Brian and ourselves, we continued to make the same mistakes. We didn’t realize that some of the things we were doing, whether it was enabling Brian or trying to appease Brian, in retrospect are completely the opposite of the right thing to do.

“I would just tell him stuff,” says Tom, “like, ‘Well, you’re just going to have to pull yourself up by the bootstraps. And just decide you’re not . . . you’re going to be a better person, and you have to put these drugs behind you.’ Because I thought he had a weakness, or he was deciding he wanted to do this. I wasn’t treating it as if it was a disease, that once he got hooked on these chemicals, it wasn’t any easier for him to stop eating or drinking or breathing than it was to give up the drugs, at least the ones he was taking. And rather than just getting mad at him, when I should just try to be helpful, try to be supportive and say, ‘Brian, this is tough.’”

“Instead of having screaming matches with him,” says Joan.

“It would be like telling somebody with leukemia, ‘Well, just get better,’” says Tom. “That’s basically what I was telling him, which he would have had no control over at this point. So I just realized I had to be compassionate and understanding and that I wasn’t going to fix his problem, but I wanted to be there for him. That we would do anything to help him. But we weren’t . . . we were always pulling his fat out of the fire.”

“And that,” says Joan, “that’s the other mistake we made.”

“Where you enable them,” adds Tom, “because they get into trouble and then somebody fixes it for them. And so they don’t realize there’s consequences to these things. And people would tell me that, they would say, ‘If you don’t ever let your son fail or suffer the consequences, he’s never going to learn that his drinking or drug use is a problem because he’ll always end up OK.’”

“That’s easy to say,” says Joan, “but it’s really difficult to do. It’s like that tough-love thing. Just kick them out in the snow, you know?”

“And that’s not right either,” says Tom. “There’s a happy medium there some place.”

“It’s very elusive,” says Joan. And it’s a quandary parents face as soon as their child stands in the crib crying. Come to the rescue. Let them work it out on their own.

That dilemma doesn’t go away, especially when your son is spiraling downward. Drinking, using, taking Adderall, probably meth, partying on the street near the police station with a quart of beer in his hands when he was 17 or 18. Opioids. Getting picked up for “acting bizarre downtown.” The Christmas he mixed muscle relaxants with alcohol and ended up in the hospital. In the ICU, intubated. That summer hanging out at that house by the Y. Getting jailed. His first DUI when the police found him in the car unconscious, then Brian fighting with them when they tried to help. Charged with resisting arrest. Becoming violent with his parents when confronted. That semester at The College of Wooster. “He got a B and an incomplete and the rest were F’s,” says Tom. “How he ever got a B in something, I have no idea.”

It was then Brian told his father, “Dad, if you don’t get me out of here, I’m going to become a heroin addict.”

“It’s such a pervasive problem right now,” says Joan, “and so many people — because of the stigma and because we think of our ability to handle all our problems ourselves — a lot of people don’t come out and talk about it.”

A lot of people don’t want others to know there’s a problem in the family. They prefer to keep up appearances, show friends and family that all is well — the kids happy, healthy and traveling the path to proper achievement, with those kids as evidence of stellar parenting, a successful, nurturing home. A façade most necessary in a culture of comparison, competition and social status. The one many of us live in. No one faltering, no vulnerabilities. Everything is great, really. To admit otherwise is embarrassing, can feel like a betrayal of loved ones you’ve been covering for.

“I think for us, that generation,” says Joan, “if you had a problem in your house, that’s where it stayed.”

“When you’re dealing with it,” says Tom, “you do feel so isolated. You think you’re the only one who has this problem. And because it’s really hard to talk about, your feelings, well, we’re just going to circle the wagons and we’re going to handle this ourselves, which is absolutely the wrong way to handle it. It makes the whole problem or situation worse.”

Stress takes its toll. Pressures seek outlets, find expression in different ways. Some coping mechanisms are better than others. Tom survived, says Joan, by “going to work.” He found refuge at the office. “Being a workaholic,” says Tom, an ophthalmologist. Part sense of duty, he says, while also admitting the problems at work were easier to deal with than those at home. “You weren’t home a lot,” says Joan.

Joan took another route. She drank. “I had such a hard time coping,” says Joan, “because I couldn’t fix it. I felt like I couldn’t do anything to help. So to get away from the pain, I drank.” A bottle of wine, maybe two. At home, sometimes on the job, working at a store downtown.

She tried to stop. “I would go on a binge,” she says, “and then I would go, ‘Oh my gosh, I’ve got to stop this.’ I knew what I was doing wasn’t right and then I would stop for a little bit, like a few days. Then any little thing would happen, and I would start again. I always had an excuse. It was all just covering up that fear and that pain of watching Brian struggle. It was a coping mechanism that became an addiction.”

She went for counseling and — just as Brian did — told them what they wanted to hear. But Tom knew her drinking was a problem, too. Outbursts at home, struggling to function around the house, the time Tom picked her up from work because she wasn’t capable of driving. “Yeah,” says Joan, “I . . . yeah, I pulled a couple of good ones, didn’t I?” Their eyes meet — traces of a smile on faces that have acquired shadows as we talk. The light has veiled the room in soft grey.

Joan sighs, continues: “My drinking was getting bad and our house was so chaotic. I just decided it was time for one of us to get off the merry-go-round. I woke up in the middle of the night and said I have a problem and I need help and I can’t handle it here. I knew I had to leave. I had to get out of the house.” That was March 2, 2006. A Thursday. By Sunday she was at the Hazelden Addiction Treatment Center, now affiliated with the Betty Ford Foundation, in Minnesota. She has been sober ever since.

Her four-week rehab was a breakthrough for Tom, too. At the end of Joan’s first week, Tom got a call beckoning him to Hazelden. “They wanted me to come to the family program,” Tom recalls. “My life’s so crazy as it is because all this stuff is going on, and I’m with Brian by myself at home, and I’m talking to this counselor, saying ‘Well, I don’t have a problem, why do

I . . . ?’”

“He was not happy,” says Joan.

“The first night that I got there,” says Tom, “just sitting there, the look on my face. . . .”

“Oh, you were so mad at me,” says Joan.

“Everybody knew I did not want to be there,” says Tom.

“And I wasn’t happy you were there, either,” she says. “I wasn’t happy you were there at all.”

But, says Tom, “it was the best thing that ever happened to me as far as understanding the family nature of the disease.” Tom stayed and worked, too, with a group of addicts and family members of addicts. “That was a huge eye-opener,” he says. “I always saw this as Brian’s problem and Joan’s problem. It wasn’t until Joan got into treatment that I realized how much of it was my problem. That’s the part hardest for me to accept — that I was such a big part of it.” The family program at Hazelden, says Tom, “saved me, too.”

‘He was doing really well then,’ says Joan. ‘He looked good, remember? Oh my gosh, he really looked good, and he acted good, too.’

By the time he returned to Wooster, says Tom, “our thought was, ‘What could we do to get Brian into Hazelden?’”

The Fenzls, including Brian’s brother and sister, Kimberly ’02, worked with Hazelden staff to stage an intervention with Brian, an unusual move for the treatment facility. Afterward Joan headed to a halfway house in St. Paul where she stayed for three months rather than return to Wooster right away.

Brian stayed at Hazelden. “He did really well there,” says Joan.

“He did,” says Tom.

Joan’s gaze drifts toward some distant image. “We visited each other several times,” she recalls. “He did really well there.”

Hazelden was a turning point for the family. Brian was out of Wooster, Joan was in recovery and the Fenzls had new understandings of addiction, its causes and power. The Fenzls also had a new appreciation for a family history of addiction, of other family members who were alcoholics. Yet just two years ago now, they say, Joan’s brother lost a son to a fate

similar to the one that claimed his cousin’s life.

The Fenzls point out that alcohol and opioids wield different powers, impact users with different forces and require different approaches to rehabilitation. “Opioids take you down really, really fast,” says Joan. “And that’s one of the reasons it’s killing so many young people — because the progression is so much faster than it is with alcohol.” Many deaths, says Tom, result when addicts, whose systems have been deprived of opioids for a while, revert to the dosage they had been taking before detox; the body just can’t handle it. An overdose, then, isn’t necessarily a suicide — although, says Joan, “People who use don’t really care whether or not they wake up. I’ve heard people say, ‘I was really mad when I woke up.’”

Tom and Joan are now deeply involved with an addiction recovery program in Wooster. They now understand the value of sharing Brian’s story, although — even in retrospect — they have no clear strategy for helping those suffering from addiction, no formula for sorting compassion from enabling, tough love from callous detachment. They do talk about biology and brain chemistry and the need to combat opioid addiction through detoxification, medically assisted treatment and years “in a pretty tight program.” Still, says Tom, the success rate for opioid addiction “is not 10 percent.”

“The statistics for alcoholism are not good, either,” says Joan.

The Fenzls were encouraged by the next turns in Brian’s winding road. He did well at Hazelden and then entered a halfway house in Oregon. From there he went to a program in California that had a more structured regimen. After several months there, he relapsed, but voluntarily returned to Minnesota, to The Retreat, an alcohol and drug recovery center in Wayzata, where he found a good support group and made good friends. He also met Melissa. “A really nice girl,” says Joan. “I think she was the love of his life. They were really good together. She was a really sweet girl, very intelligent, had lots of goals.”

Brian and Melissa moved to Oregon where they worked on a farm, a communal enterprise, caring for the earth, composting, tapping wind power for electricity, making jams and jellies. They rented their own place, enrolled at the University of Portland. This would’ve been 2008, on into 2009. Brian was 25, 26. Tom and Joan visited; Melissa and Brian came to Wooster for Christmas, bearing gifts of jam and jelly. Life was good.

Later in 2009, though, a visit to Portland revealed that Brian was backsliding and, when he came home to Wooster for Thanksgiving, he got violently sick. “He was having withdrawals,” says Tom. Diarrhea, vomiting, shaking, sweating. “Like having the worst flu in the world,” says Tom. Brian went out and got something, they say, looking back, to ease the pain and get him back to Portland.

The following week there, Melissa found him in a hotel room, on heroin. She called the Fenzls, who got him into a detox facility back in Ohio. Then there was the intensive outpatient program in Portland, and more desperate phone calls from Melissa. So Joan flew to Portland and drove Brian back to Minnesota, delivering him again to The Retreat — “they were so nice to him,” says Joan, “they really liked him there” — and then a halfway house, then getting kicked out of the halfway house, and Melissa breaking up with him, and then Brian living out of his car. A life unraveling.

“I do need to backtrack just a tad,” says Joan, interrupting the chronicle of descent. It was the summer before that Thanksgiving, she says, when Brian and Melissa were in town for a family wedding, and right before that a friend — a good and close friend from The Retreat — had just died in London of an overdose. “It really threw him for a loop,” she says. “That was the beginning of the downturn.”

“That really was when things started to go off the rails,” Tom agrees. “Brian was one who took everything to heart.”

“I think about how he had a tough life,” says Joan. “It was tough to be Brian.”

Brian landed at a Florida treatment center by the end of summer 2010, and spent the fall there, left, returned, was in an outpatient program, had a job at a coffee shop. Tom and Joan were again optimistic. “He was doing really well then,” says Joan. “He looked good, remember? Oh my gosh, he really looked good, and he acted good, too.” Through Christmas and January.

Tom’s father turned 90 on February 2, 2011, and the family celebrated at New Smyrna Beach, Florida. Brian took the train to join them. “He was with us for the weekend,” says Tom. “He seemed great. I was so happy because he looked so good and he came to my dad’s birthday party.”

But in March Tom got a call from Brian’s phone. “It’s this girl telling me that Brian has overdosed, and he’s at a hospital in whatever the name of this stupid town is. I can’t remember.”

Brian checked himself into a detox center before returning to the treatment facility there in Florida. Tom and Joan stayed in Florida and went to the facility where a counselor told them, “You can’t take him with you. You can’t try to help him. If you do that, you know you’ll undo all the good that’s happened.”

Brian called Tom’s phone, but the counselor took the phone and talked to Brian. “She wouldn’t even let us talk to him,” says Joan, “telling us we shouldn’t speak to him or see him or help him in any way.”

“He wanted to meet with us,” says Tom.

“She said, ‘No, don’t talk to him,’” says Joan. “She talked to him. We heard him. We heard his voice.”

“See, that’s what he wanted to do,” says Tom. “He wanted to see us.”

The counselor told us, “‘Just let him go,’” says Joan. “So we listened, because at that point, we didn’t even know which way was up. We just thought they knew what they were doing.”

Tough love.

The Fenzls then visited Tom’s parents before returning to Ohio. Brian called again the next day. “We got a phone call from him there,” says Joan. “And he said, like he had said a million times before, ‘I’m going to kill myself.’” She followed professional advice. “I hung up on him,” she says. “And I never heard from him again.”

A day or two later, back home in Wooster, Tom and Joan got a call from the Boynton Beach police. “We both knew,” she says.

It was over.

Over — except for the memories and regrets, the hurt and healing, and the talking. Talking to try to make sense of it all. Talking to maybe help somebody else. “We didn’t think it could happen to us,” says Joan. “We were unprepared, unaware of lots of things,” says Tom. “Hindsight is always 20/20, but we didn’t realize what the effect of taking drugs had on people and their personalities. Unfortunately, we know now.”

Kerry Temple is editor of this magazine.