Illustration by Curtis Parker

Illustration by Curtis Parker

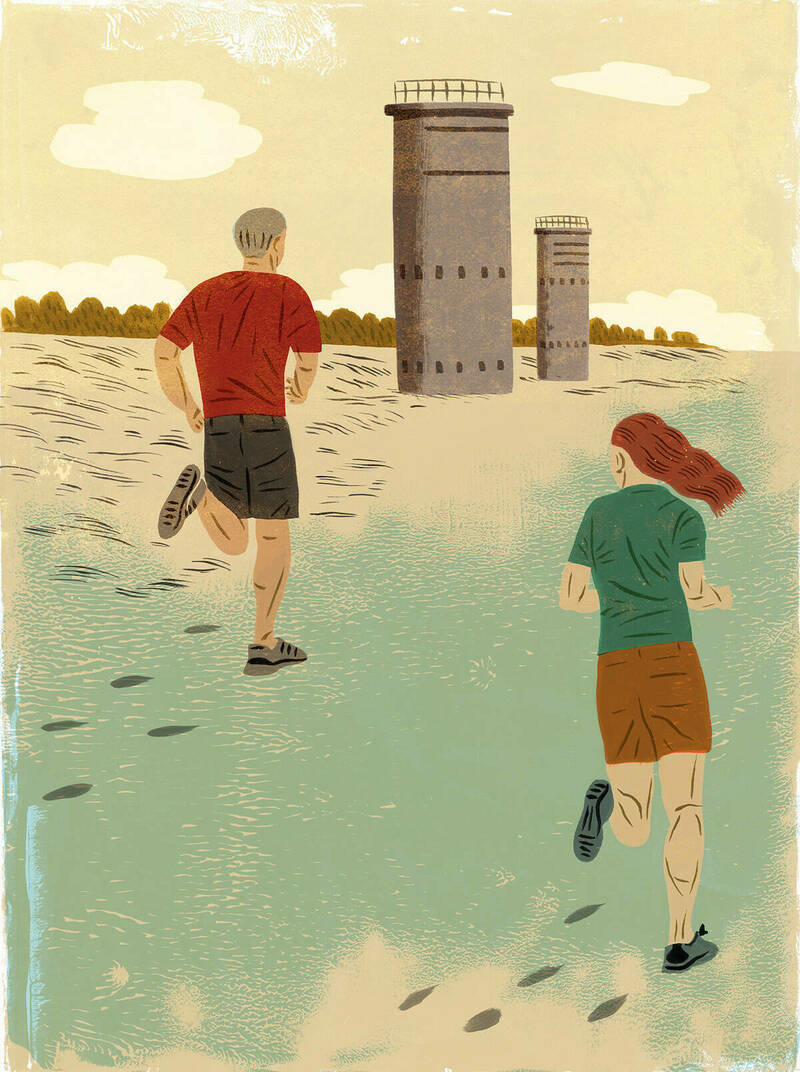

The two abandoned lookout towers may have been built during World War II to monitor enemy operations off Cape Henlopen, Delaware, but their presence on that pristine stretch of beach has always seemed eternal to me. Back then, optical tracking equipment peered out horizontal slots at the top of the two sand-colored concrete cylinders. Watchers with machine guns stood ready to fire on Germans. But I reckon that then as now the only activity they witnessed was porpoise families playing beyond the wave line while motorboats buzzed the coast and cargo ships slowly smoked out of Delaware Bay. Captains of those ships surely have likened the towers to giant sand castles waiting to be washed away.

Beach erosion threatens the towers with that fate today. When I was a little girl, they were located high above the beach on a grassy dune. By the time I reached adulthood, they hung around shyly at the back of the beach in front of the dune. Now they stand strong in the whitewater whenever nor’easters hit the coast in winter.

It isn’t lost on me that my eternal towers may disappear well before I leave this world. But one summer day in 1990 when I took a beach stroll with my silent father, the two sandy towers offered themselves as a natural destination as we walked among the pure and simple elements of wind, sun and water that left no place for the problems of yesterday, today or tomorrow.

I call my father “silent” because that is what he was. At age 65, he had stopped talking the year before and probably uttered fewer than 50 words until the day he died in the cold second month of 1994. This was astonishing for a former litigator who once argued complex intellectual property cases before juries across the country. The few words he did speak came at intense moments: “Mama’s great-aunt was an Austrian countess!” he had shouted when we were at the Kennedy Center Concert Hall listening to Strauss’ “The Blue Danube,” confirming the power music holds on memory.

We had arrived at the beach just after the lifeguards’ 5 p.m. whistle calling swimmers out of the water. It’s always seemed ridiculous to me, but only after the guards drag back their white stands, lay them on their sides and leave the beach may bathers return to the water at their own risk. That late afternoon the beach was just about empty despite the pleasant conditions, the waves of the rising tide breaking with flourish and spray but well-mannered and predictable.

As usual, when I looked at my father, I was troubled by the simpleton nature of his brown eyes, proof that his Alzheimer’s-tangled neurons were messing with his lively spirit. In Dad’s eyes, I saw the quiet serenity of a soul resigned to its trapped and isolated fate.

We left our sandals at the end of the narrow boardwalk, just two figures in bathing suits. The wind was blowing enough to billow my father’s thinning white-grey hair. We walked north with the waves on our right, the white buildings of Cape May visible about 10 miles to the northeast across the mouth of the bay. A tanker was making its way toward the indigo-flat of the Atlantic Ocean. We didn’t get far before we turned east for a dip, diving and jumping waves, digging our toes into the mucky sand and breathing in the scent of the sea.

I relished how the late afternoon sun warmed my wet body and heated the sand to a perfect temperature, the grains caressing the soles of our feet. The breeze brushed our arms lightly, and I could feel the delicious tightness of caked-on salt. We paused to watch seagulls gathering to feed. And we listened. The duet was unmistakable: a melody of lighthearted squeals over the rhythm of waves gathering, crashing, receding; gathering, crashing, receding.

I was a child again, wanting to prove to my father that I was the best, that I deserved his love.

Lulled by the elements, I had forgotten my father was sick. We glanced at each other, happy in the moment. I noticed that his legs remained long, muscular and slender down to his Grecian-statue feet, and I smiled, remembering how our dog licked his toes when I was little.

“Hey, Dad, do you want to race?”

He pursed his lips, turned his eyes toward the lookout towers and back at me. Then, before I knew what was happening, he started running down the beach. I was stunned. Were his eyes on fire, or was I hallucinating?

I sprinted after him, running hard to catch up, because after all, I had inherited his competitive spirit. He felt me gaining and ran faster. Dad: Ohio native, World War II veteran, Notre Dame graduate, admirer of Knute Rockne, Vince Lombardi and George Allen. How many times had he mimicked Rockne giving a speech to his Fighting Irish? “You’ve got to win, win . . . win, win, win,” Dad would say, “’cause that’s what life is all about.”

My heart fluttered. Dad was here, yes, he was here; the real Dad, making an appearance.

We ran neck and neck toward the sandy lookout towers, our eternal finish line. Just a father and his daughter encouraged by the wind, powered by the sun, cheered by the waves. I was a child again, wanting to prove to my father that I was the best, that I deserved his love. The sand shifted under our feet, and I lunged forward — 35 years his junior, could I stick it to him?

Then he fell. His knee hit first, his forearm broke his fall, and his head followed with a soft thud.

I was there in seconds, kneeling at his side. “Are you OK, Dad?”

He glared at me, the fire in his eyes turned angry.

I glanced back at him. I felt shame.

Like a parent looking at a child, ashamed I didn’t do my job . . . build his confidence . . . let him win . . . show him his brain was capable of working perfectly. That he was still strong. That he was a winner.

How stupid I was.

My savvy father, he read it all. It wasn’t pity he saw. This was deeper — he saw my pain. He understood I was upset because I thought that I had gotten in the way of his winning against his ugly disease.

I helped him up. “Dad, you were good. You are fast.”

We locked eyes. He had tears to match mine. I moved toward him and let him hold me. And he did. We stood there, a solitary outcropping, and resigned ourselves to the beauty of the now — in the shadow of our eternal towers — and let the sun and wind and ocean reenter our spirits. We took advantage of the only good choice left.

At some point we separated. I gazed into his eyes — the fire was gone and limpid simpleton was back. I turned away, seeking solace in my lookout towers. The tide had nearly reached the first tower. That night they would be standing in water, one tide closer to disappearance.

No. One tide closer to their physical disappearance.

Seized by a new clarity, I understood. Then and there, I claimed my sandy lookout towers and my fiery father as I wished to remember them. Both of them, mine for eternity.

Jane Mobille is a Paris-based executive and life coach and editor of the quarterly magazine at the Association of American Women in Europe. She is a daughter of George T. Mobille ’48 and mother to Claire-Elizabeth Gonnard ’16 and Jacques-Alexander Gonnard ’21.