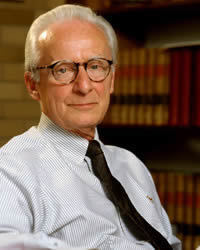

I am a fairly undisciplined and compulsive reader, but I sometimes think the number of books Notre Dame’s Ralph McInerny has written exceeds the number of books I have read. Along with the countless volumes of philosophy, literary criticism, cultural criticism and poetry that the late Michael P. Grace Professor of Medieval Studies left behind when he died on January 29, are dozens of potboilers, many of them murder mysteries.

My favorites among this subset of “McInernia,” are the novels Ralph set at Notre Dame. All of them have groan-inducing puns in their titles, such as On This Rockne, Irish Tenure, Lack of the Irish, Celt and Pepper and the forthcoming Sham Rock. (When it came to resisting puns, Ralph was utterly powerless. He once unblushingly began a lecture on G.K. Chesterton this way: “It takes a lot of gall to talk on Chesterton, and my gall is divided into three parts…”)

- Related article

- In memory of Ralph McInerny

Ralph’s Notre Dame murder mysteries are lavish in local color and character, and he often included thinly disguised friends and colleagues as minor characters. I was always delighted and amused by the good-natured teasing involved in these cameos until, in a couple of the stories, I noticed a character from Notre Dame’s PR office with a name suspiciously like my own.

“All this guy does is hang out in the back bar of the University Club, drinking, telling cynical jokes and picking fights,” I grumbled to my wife. She replied that she could fondly remember several times we had sat with Ralph in that very room, drinking merlot, joking and gossiping about the peculiarities, splendid and otherwise, of Notre Dame. She gently added that if I didn’t exactly pick fights on those occasions, I did from time to time express vehement and contrary opinions. “In other words,” she shrugged, “Ralph’s got your number.”

She was right, of course. Nor was mine the only number this incisively witty and wonderfully convivial man had, which is among the reasons he could be such a formidable controversialist. Whether his aforementioned gall was divided or not, he had gall aplenty, and he could be positively gleeful in flushing out, strafing and demolishing an opposing viewpoint, especially if that viewpoint concerned the affairs of the Catholic Church.

But if he spoke and wrote daggers, he used none. Too honest to shrink from genuine disagreement, Ralph also was too kind to keep an enemy. “I have never doubted the sincerity of those I have called dissenting theologians,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Many of them are friends of mine.”

Among those sincere believers with whom Ralph could vigorously disagree were many men and women of the Catholic Worker movement. But any of them will tell you they had no better friend than Ralph McInerny.

During the years since Ralph’s retirement, Notre Dame theologian Michael Baxter, an active member of the Catholic Worker community in South Bend (and a minor character in one of Ralph’s Notre Dame mysteries), was a frequent and welcome visitor at Ralph’s house in Holy Cross Village. They liked to talk about theology and Catholic history, but Ralph would often ask after the affairs of the Catholic Worker houses. Not only the plights and idiosyncrasies of the guests would interest him, but also the grocery, heating and repair bills. Often Ralph would nonchalantly remark, “I can help with that,” scrawl an eye-popping sum on a personal check, and hand it to Baxter, never letting his right hand know what his left hand was doing.

Charity was perhaps the only activity in which this eminently meticulous philosopher could be so careless.

Michael Garvey is Notre Dame’s assistant director of public information and communication.