Editors’ note: Alan Sondej ’74, whose name — pronounced “Sunday” — is synonymous with selfless love and service to the least among us for a generation of Notre Dame alumni, died 25 years ago in relative anonymity. One Domer knew Sondej before he came to Notre Dame and has never ceased marveling since.

I was in my early 30s in 1989, tending to my latest career move, when my brother James Rogers ’69 passed on the news that Alan Sondej had died. He’d read about it in Notre Dame Magazine and he called me at home on a Sunday night and told me what he knew, providing an answer to a question we had posed just two weeks before, when our brother Casey had flown in from Hawaii to attend his high school reunion. Had he seen Alan?

No, Casey had not, and no one at the reunion had known much about Alan. We had speculated on where he might be. It was interesting to do so, because Alan was such a unique individual, forever a member of our family Hall of Fame. I was certain he was somewhere far away, doing what many of us would never consider doing as we play out our lives in the free-market world of ambition, advancement and vain acquisition. He was probably doing good for people — just that, nothing more, nothing less.

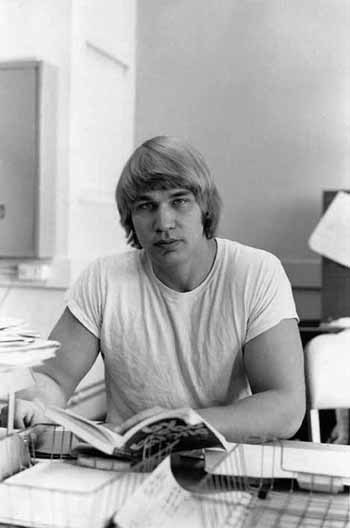

Alan Sondej was a sociology major who graduated in 1974 and stuck around campus for a few years thereafter. Almost everyone who attended Notre Dame in the 1970s would remember him as “the big guy who collected money for the hungry outside the dining hall.”

When James told me about Alan’s death, and how he had died, a sickening feeling came over me, a feeling much worse than just sadness. And it’s always been curious to me that I had such a feeling, for I could not count myself among Alan’s closest friends.

I first met Alan when I was 10 and Casey and Alan attended a private military high school in Manhattan. Alan was already big, even as a freshman. He was strong and played football and was about as muscular as anyone I’d ever seen. Casey told me stories of Alan’s feats as a weightlifter. He looked ferocious to me, but it didn’t take long to see that this was not what he was like inside. In fact, it wasn’t long after Alan started coming around our house that Casey told me he’d quit football because he was afraid he was going to hurt someone.

Alan came to our house a lot over the next four years. He was always quiet and polite. When they went separate ways for college — Casey to West Point, Alan to Notre Dame — I figured we’d remember Alan as that unique guy who wouldn’t play football because he was afraid he’d hurt someone.

But Alan stayed present in our minds. Casey kept us up with his exploits. We knew he was studying and not playing football or driving a car — he never got a driver’s license — and wasn’t doing anything distinguished beyond that, as far as we could see. Eventually Casey learned that Alan had stayed at Notre Dame after graduation, collecting money for the hungry. I remember wondering, Why is he doing this? Why isn’t he getting a job and worrying about making money like everyone else? Clearly he had taken a benevolent stand, but I had to admit I didn’t know him at all. And I wished that I did, so I could get some answers.

Meetings with Alan

After high school, I spent three years at West Point before transferring to Notre Dame in 1977. I soon ran into Alan, still at Notre Dame where he’d been for almost eight years, still collecting money for the hungry. I’d heard how he would stand outside one of the dining halls with a milk jug and solicit donations. Everyone seemed to know who he was. A smile would come over people’s faces when I asked about him. He evoked a reaction, but then no one could say that they really knew him. It was as if they wondered the same things about Alan that I did and had never figured it out either.

One winter night I went to Corby’s and saw him standing at the bar. I recognized him immediately and reintroduced myself. I asked if he wanted a beer, but he said he wasn’t drinking, that he just liked to be out and talking to people. We had a long conversation about Casey and why I’d gone to West Point and Notre Dame, and why he was still at Notre Dame so long after he’d graduated. I asked about his notoriety. And he told me yes, he was still collecting money from time to time, but he was also speaking on campus about world hunger and had traveled overseas and seen the problem firsthand.

At first, his goal had simply been to collect as much money as he could — about $25,000. Then Father Hesburgh became aware of him and opened Alan’s eyes to how he could make a bigger impact. Father Hesburgh sent him to places like Bangladesh and Guatemala to help hunger relief efforts and to bring home the lessons of what he saw to solicit larger donations from larger groups. He was shifting from one way of addressing the problem to another, much bigger way.

It struck me that night how easily he could warm up to someone he hadn’t seen in so long. He seemed as interested in what I was doing as I was in him. But he was still an enigma to me.

The next time I saw him was in late March. He was walking in the snow on Eddy Street. I stopped my car and offered him a ride. He had a duffel bag slung over his substantial shoulders and he said he was going to the train station.

As we drove through town in my brand-new Corvette, a perk from my days at West Point where cadets were paid a salary as members of the United States Army, I found myself wondering what he was thinking. Perhaps he was bewildered at the extravagance, or was thinking of the mouths he could feed with the money it took to buy that car. I know I was thinking of those things, and feeling somewhat embarrassed, though the thought of doing anything about it was fleeting; I wanted it to go away.

Most likely, though, Alan was passing no judgment at all. He said he was headed back overseas; his work at Notre Dame was over for now. He thanked me for the ride and I wished him good luck, and that was the last time I saw Alan Sondej. Afterwards I thought he probably had been looking forward to the walk; he’d probably wanted some exercise, and yet he was too polite to turn down my offer lest he hurt my feelings.

Casey and Alan fell out of touch sometime in the ’80s. And Alan couldn’t have attended their 20th high school reunion because he had already died, in March 1988. My reaction when I heard the news got me thinking about death, because I needed an explanation for the incredible sadness — a feeling almost like horror — that I felt that night on the phone. It was not only the fact that he’d died, but the way he had died, that affected me.

Dwelling on death

We don’t generally dwell on death, but when it hits the finality of it can affect one’s perspective. Funerals remind us that someday we, too, will be there. We cry for ourselves, our collective selves, really. Indeed, at Alan Sondej’s funeral, as we later learned, his visibly shaken sister had spoken of her brother and said, “We cry today as a family, but they are tears of joy, not of pain, for being blessed with someone as special as Al.” That’s a beautiful sentiment, but it’s a hard one to attain in the face of such grief.

I wondered: Had he been married? Had he started a family? Had he been happy? What had his life meant in the end?

Alan had died as a volunteer fireman, from complications from burns he’d suffered while trying to save a life in a fire. It all seemed so sadly consistent. There he was again, out helping others, not being paid. Once back in the developed world, where the size of one’s bank account is the most prominent statement of success or failure, Alan Sondej had quietly gone about the business of helping others, and he had found anonymity — and his demise.

Alan had been taking graduate courses at the University of Maryland and working for the Hyattsville Volunteer Fire Department. He was planning to go back overseas to teach sustainable agriculture techniques. On January 27, 1988, on what was scheduled to be his last night with the department, his unit was called to a house fire. Hearing that a woman was trapped inside the house, he and other firefighters went back inside to find her. A flashover engulfed the room Alan was searching in flames.

It turned out the woman had escaped to a neighbor’s house just before the firefighters arrived. Alan was badly burned, and although he briefly appeared to be recovering, his burns put a massive strain on his heart and other organs. He suffered for seven weeks and died on March 16.

Remembering Alan

I’m still going about my business these days, holding my own in the terms of western success, and still searching for answers. We publicize celebrities so well in our society that we seem to enjoy making people famous, or infamous. We put actors, athletes and murderers on the covers of all the same magazines. We reward people we admire for leading large corporations and winning elections or national championships and rarely question our values in any real depth.

Wasn’t it typical that Alan Sondej died in obscurity? That even at his high school reunion, over a year after his death, no one knew what had happened to him? It was his kind of living that could teach us something. Maybe by taking the time to remember him, we might yet learn something from his death.

Terrence Rogers graduated from Notre Dame in 1979 with a B.A. in psychology and a B.S. in electrical engineering. After a long business career he returned to Notre Dame and obtained a Master’s degree in International Human Rights Law. While here, he raised over $17,000 for the Holy Cross Missions in Bangladesh. He has written about human rights violations in law reviews, and is working on a memoir about his days at Notre Dame. Email him at tscrogers@aol.com.

The Alan P. Sondej Memorial Fund, administered by the Center for Social Concerns, supports disaster relief efforts in the developing world and antimalarial bed nets in Africa. Donations may be made directly to the center, or through the Development Office by referencing fund number 370343. Alan’s classmates Duke Scales ’74 (escales1@bellsouth.net) and Jerry Samaniego ’74 (jsamaniego@cfmsd.com) direct the deployment of the funds.