Football, the Grotto and Mass at the Basilica were the only antidotes for the bleak fall and winter of 1961-62, my freshman year at Notre Dame. Despite my version of hard studying, I received pink slips in three of my five subjects after midterms. I redoubled my efforts, but, returning to my Farley Hall bunk in the evenings, I found 343 had become the designated rumpus room for at least seven of my hallmates. Sleep before midnight was generally out of the question. If I happened to doze off in the din, I might be awakened by imminent or actual urinary incontinence to discover my hand immersed in a container of warm water amid the guffaws of several juvenile 18-year-olds. Homesickness set in with a vengeance.

By sophomore year, I’d had enough of roommates. Accordingly, I arranged for a single room in the basement of Lyons Hall. Now in pre-med, studying for the notoriously difficult exams in courses taught by Emil T. Hofman and Brother Raphael Wilson, CSC, it was back to my solitary study nook of choice — the stairwells — for me. Then, one football Saturday, Bob Koches ’63 heard me strumming my guitar and singing a Kingston Trio song and he suggested I try out for the Glee Club.

Determined to achieve a GPA that would not cause laughter on medical school admission committees, I had not considered joining anything extracurricular, let alone the Glee Club, whose members I assumed were music majors. Bob corrected my misimpression and took me over to the rehearsal hall to meet Professor Daniel H. Pedtke, “The Dean.”

- Can’t get enough Glee?

- Ringing Out the Songs

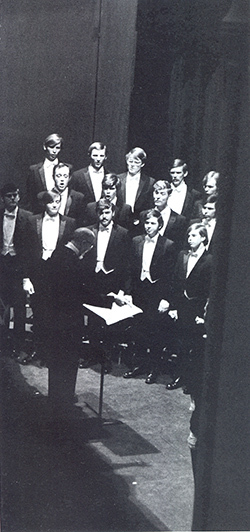

Within minutes, Dean was playing scales on the piano for me to imitate, and with an approving nod and a gentle “yeah,” he told me to sit with the second tenors when rehearsal began moments later at 5 p.m. I knew none of the songs, but when the 90-plus men’s voices broke into the “Victory March” in four-part harmony, I was suddenly all chill bumps and hooked for life. The memories of freshman year and all the laughs at my expense evaporated. The Glee Club became my fraternity on a campus where fraternities were not allowed.

Rehearsing every weekday evening from 5 to 6 became part of my fiber for the rest of my time at Notre Dame. Once I had learned my part on a few songs, I became a nightly annoyance to some of the veterans, boyishly bugging them to sing some more as we walked from O’Shaughnessy to the dining hall after rehearsals. I could never be accused of having an operatic voice, but I do have reasonably good pitch and volume and, in my enthusiasm for four-part harmony, I often erred on the side of being too loud rather than blending. Dean taught me to have a better feel for a song and to back off when appropriate, but I deserved the mostly affectionate reputation I got of being a ‘screamer.’

Soon I was traveling. Like most young men who can carry a tune, many of the friends I made in the Club were baritones, but the Indiana Bus Company’s buses carried only 40 riders — 39 singers and Dean. Baritones were plentiful; tenors were not. Consequently, through no great talent of mine, I became one of the regulars at off-campus concerts and in these travels made the closest friends of my life. (One in particular was a first tenor. I doubt there are many people who can claim a “best friend of all time” whose name is the same, spelled exactly the same way. John Fisher became Fish I and I became Fish II. At John’s wedding, the officiating priest quipped that he hoped he would remember which John Fisher should recite the vows. I’ve never been prouder to be a Best Man.)

Dean Pedtke was a one-of-a-kind choral director who could say everything with just his hands and facial expression. There was no grandiose, wild waving of both arms in time. He kept rhythm with his hands in front of his chest, mostly concealed from the patrons. With just his fingertips he communicated the starts and stops in a piece without any confusion and, with a simple rotation of his hands, the louds and softs in a song or hymn that can move an audience to tears or exhilaration. And in that face — not handsome but careworn — were the most expressive eyes I’ve ever known.

The majority of Clubbers didn’t notice these things. Yes, they appreciated Dean as a music director, but we thought Dean was cool.

We were mesmerized into knowing exactly what kind of a sound he wanted us to produce — soft and tender, or full-throated and boisterous. Although we knew intuitively what to do, at times stage-fright, sagging pitch, fatigue or simply trying too hard prevented some of the chords from locking. We could tell from Dean’s countenance at the end of a number whether he was pleased with our performance. A neutral expression to us followed by a perfunctory turn to the audience to accept the applause indicated that our interpretation had been adequate. But if Dean paused for a moment after the final chord and gave us a fatherly nod and a wink before turning around, we would know we had nailed it. His unassuming visage, dress and gentle nature could never be described as charismatic, but the sheer depth of his character, personal goodness and credentials as a musician made an indelible mark on each of us. Every time he stepped up to conduct us, our focus was to please this man whom we loved. We were unified in our admiration for Dean.

Our audiences might have chosen the Norman Luboff Choir or the Robert Shaw Chorale for technically better performances, but some connection to Notre Dame put them in the seats. To them we may have personified Notre Dame or just stirred their pride in being Catholic. And Dean could always make them glad they came with his interpretations and unique mix of classical pieces, famous songs from yesteryear, show tunes, and comedy trios and quartets. When we sensed on the risers that a performance was going well, we couldn’t wait to get to the college-songs finale. We knew audiences would jump to their feet immediately when they heard Dean make the “Victory March” ring. It is simply the gold standard. No other fight song is so universally recognized or loved.

There was a group of us within the Glee Club whose affection for Dean and for the Club rose to a different level altogether. It had to do with our fervor for singing, for Notre Dame, and for this quiet and decent man who could take average voices to unexpected heights in harmony on stages all across America. Hero worship would best describe our love for Dean Pedtke, which was ironic. He was a man who wouldn’t light up any room he entered — unless the Glee Club happened to be there. We often smiled at his use of exclamations such as “Gee!” and “Golly!” in casual conversation. The majority of Clubbers didn’t notice these things. Yes, they appreciated Dean as a music director, but we thought Dean was cool.

We referred to the others as the “A Group.” We were the “B Group.” That stratification had a history extending back to an overnight, off-campus concert before my time when the Club needed two hotels to make up a room shortage. One hotel was rather posh and the other was rather not. Some Clubbers rushed to be at the head of the line for the better hotel. They became the “A Group.”

Through the years these groups took on distinctive personalities. The “A Group” were of the early-to-bed, buttoned-up sort. “B Groupers” would stay up late after concerts scouring the host city for a quiet bar in which to keep harmonizing, even if the quality became suspect after a few beers and with no Dean to direct us. But with the right mix of voice parts, a bunch of ordinary-looking college guys could stun a bartender and remaining patrons by breaking into the “Victory March.” After that debut and a few of our favorite songs, we’d never buy another beer. When no bars were nearby, a six-pack and a motel stairwell would do quite nicely for a post-concert “scream” before we turned in at 2 a.m.

The rest of my Notre Dame years sped by. The Glee Club actually facilitated my studies and helped me get into medical school by giving me an outlet to unclutter my mind. Dean made use of my strident voice and “hamminess” by featuring me in some comedic songs and in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Trial by Jury. I became so accustomed to singing choral music from 5 to 6 on weekday evenings that when I arrived at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond, I again felt somewhat lost.

So, I started my own glee club. On the appointed day about 40 would-be singers showed up to join — all women. There was nothing else to do but conduct the group, which I did for two years.

Dean Pedtke retired in 1973 after 35 years as the Glee Club’s conductor. He died in 1976, but his influence on me has continued for more than 50 years. It led me to sing in the Naval Air Training Command Choir in Pensacola, Florida, during my service as a Navy flight surgeon. I sang for 15 years in a barbershop quartet and directed a barbershop chorus for seven. Now, although my formal choral music days are behind me, I’ve come full circle and have been playing guitar and singing Irish songs in a bar every Tuesday evening for the last 11 years.

The “B groupers” still get together. Though time keeps diminishing our numbers, some 10 to 20 of us from the early 1960s meet before and after a Notre Dame football game somewhere and sing ourselves hoarse for our wives and families. Some of our harmonies don’t seem half-bad to us, but if Dean is listening and wincing is allowed in Heaven, I’m sure he has done it. Or at least said, “Gee.”

Dr. John Fisher is an infectious disease specialist who teaches at the Medical College of Georgia near his home in Augusta.