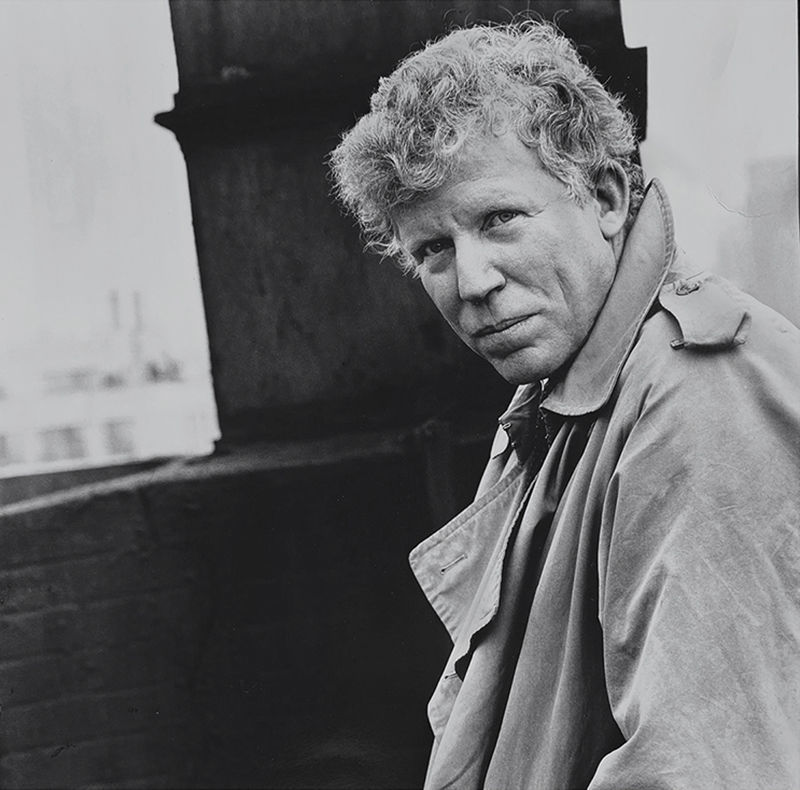

Photo by Sigrid Estrada

Photo by Sigrid Estrada

When Robert Sam Anson ’67 died, The New York Times devoted a half-page in its November 8 Sunday edition to the journalist’s obituary, calling him “a virtuoso of magazine writing.” Vanity Fair, a slick magazine highly respected for its literary journalism, described Anson in a 1,000-word tribute as an “intrepid, incisive reporter and a stylish writer” who “excelled as a maestro of the long-form magazine piece.”

Anson began his career shortly after graduating from Notre Dame as a war correspondent for Time magazine, plunging into the combat zones of Vietnam and Cambodia. Later known for his penetrating profiles of prominent cultural figures, he also wrote a half-dozen books scoping the edges of politics and societal tensions. His riveting account retracing the last-known tracks of Daniel Pearl, a Wall Street Journal reporter who was kidnapped and beheaded in Pakistan in 2002, was classic Anson.

He was, according to an Esquire editor, “the last of a breed of broad-shouldered, bare-knuckled, ’70s magazine journalists who will chopper into any hellhole on earth and come back with an epic story.”

Anson was also difficult — brash, bullheaded, passionate, pugnacious. No one knew this better than Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, Notre Dame’s president from 1952 to 1987. The two met when the priest gave the Cleveland freshman a ride to campus after an antiwar demonstration in South Bend. The president told Anson to stop by his office anytime, preferably after midnight, just knock on the door. The pair would have a number of conversations — many of them heated — over the next several years.

Anson, a product of the turbulent ’60s and a campus activist, was a ringleader in launching The Observer in 1966 as a liberal, independent, student newspaper. Anson’s provocations — and a column calling for Hesburgh’s resignation — rankled some administrators who called for Anson’s dismissal. Hesburgh told me decades later that even Anson’s mother had asked the president to kick her son out of school — he was embarrassing the family.

But Hesburgh refused, saying that would give the dissident some satisfaction. Besides, he added, he believed in freedom of the press, and that belief meant little if it didn’t extend to his own campus — even if he was the target. Anson, Hesburgh added, caused him more trouble than any student during his 35 years as president.

So it was especially poignant in 1970, three years after Anson’s graduation, when a Time editor called Hesburgh to say their young war correspondent had been taken prisoner by the North Vietnamese, and his best hope for release was Hesburgh’s intercession. Other journalists captured during the war had been executed.

After considering his options, Hesburgh picked up the phone and called an old friend — Pope Paul VI. With a note of humor in his voice, he later said to me, “I figured I wouldn’t be much of a priest if I didn’t believe in forgiveness.”

Anson talked over lunch one day, recalling his capture, being handed a shovel to dig what he assumed would be his own grave, then digging with a gun pointed at him, remembering how the cold metal felt when pressed against his forehead. “Hòa bình,” he said. “Hòa bình.” Peace, peace.

Anson was released a few days later and pointed down a road toward freedom. The Time editor told Anson he owed his life to Hesburgh.

Still, 30 years later, when Anson wanted to visit with Hesburgh, he asked if I would go ahead of him, as his ambassador, to see if Hesburgh would even meet with him. Surprised but willing, I spoke with Father Ted and would learn that he and Anson had crossed swords even after Anson’s student days. Hesburgh grumbled, told me his Anson stories and eventually said, “Sure. If he wants to, I won’t say no.”

I met with Anson right before he headed to Hesburgh’s office atop the library that bears the priest’s name. “Can’t remember being so nervous,” he said. I met with him again, three hours later, right after his visit with Father Ted. “I’m a foot off the ground,” he said, his exuberance obvious. “I don’t recall ever feeling so good.”

A week later I got this email from him: “Truth is, I have always had enormous personal regard and affection for Fr. Hesburgh (well, there have been a couple of significant exceptions, such as when he was going to throw me out for reprinting the word ‘screw’ in The Observer), who is literally the most important man in my life and how I see the world. Our trouble was always over issues: Vietnam, free speech, governance of the university, athletes sexually assaulting women, South Africa divestment – that kind of stuff. A lot of it was generational: ’50s liberal versus ’60s liberal. And some of it — probably more than some, looking back — was Freudian slash Oedipal. He was the father I never had; I was the rebellious son. We clash, we reconcile, we clash, and at the end — when yours truly is much older, a father himself, and much more understanding about lots of things — we reconcile. I still think that I was right about all the issues, and I’m sure that Fr. Hesburgh (who just happens to be one of the great men of the American century) still thinks he was right, too. But, ya know, there are many more important things in life than politics or who’s right and who’s wrong. Love top of the list.”

Kerry Temple is editor of this magazine.