The man I most admired died six years before I was born. My father, a staunch Notre Dame fan, talked about him with reverence. I was told that he was forthright, honest, inspiring and a champion for the cause of good sportsmanship. From an early age I remember hearing the “Win One for the Gipper” story and the exploits of the Four Horsemen. His legend inspired me as a young football player, and his legacy was one of the reasons I entered Notre Dame in the fall of 1956. Now, almost 50 years later on the 75th anniversary of his death, I have had the opportunity to remember my hero—Knute Rockne—in a very special way.

Knute Rockne’s leadership ability and his teachings of sportsmanship were always special to me. Throughout my life I read everything I could about the great coach.

Over the years I collected almost every book written by, or about Rockne—more than 40 volumes. I even purchased most of the Notre Dame yearbooks associated with his life as a student, assistant coach, and head coach. While in high school I traveled to Cedar Point to practice football on the very beach where Rockne and Dorais perfected the forward pass in the summer of 1913. And, during my senior year at Saint Edward High School in Lakewood, Ohio, I was fortunate to meet Knute Rockne Jr., who came to see me play football. After high school I had an offer to play football at a small college in Ohio, but Notre Dame and the legend of Knute Rockne beckoned me to Notre Dame.

Over the years, I admit that I have been somewhat obsessive in my desire to walk in the footsteps of the great coach. I have visited his birthplace in Voss, Norway;, the Logan Square neighborhood in Chicago where he grew up; the halls he lived in as a student; the beach at Cedar Point; the three houses where he lived in South Bend; the stadium locker room where he fielded his last team in 1930; the desolate hillside at Matfield Green, Kansas, where his airliner went down; and his final resting place at Highland Cemetery. I purchased the grand piano that stood in his East Wayne Street home 40 years after he died with the expectation that it would bring some Rockne karma into the McKenna home in Texas. I even contemplated writing a book about the man, except it has already been done 25 times by writers far more adept than me.

At Notre Dame, after a short stint in the seminary, I majored in fine arts—paintin_g_ to be exact. After graduation, I worked briefly as a commercial artist before enlisting in the U.S. Air Force. For 27 years I traveled the world serving in a variety of jobs—intelligence officer in Japan, administrator on the Air Staff at the Pentagon, exec for a forward air controller outfit in Vietnam, and a base commander in England. Through the years, Notre Dame and Rockne were never far from my mind. In fact, when the first of my four sons was born, I named him—what else?—Michael Rockne McKenna (and today Michael is a football coach in Texas).

Throughout my Air Force career I had it in the back of my mind that I would somehow resume my art career when I left the service. About 10 years before I retired, quite by accident I stumbled into the world of sculpture and realized I had some talent. I started creating simple forms at first: bas reliefs, small portraits, basic compositions. I visited museums and sculpture parks and studied every anatomical book I could lay my hands on. Throughout this learning process, I was thankful for the drawing and design basics taught by my Notre Dame professors, Robert Leader and Dr. Stanley Sessler. By the time I hung up my blue uniform for the last time, I felt that I was ready to hang out my shingle and call myself a sculptor. (Although I must admit that there were times I feared the “sculpture police” might raid my studio and arrest me as an imposter!)

My first commissions were of military leaders. I created portrait sculptures of Generals Billy Mitchell and Jimmy Doolittle for the Air Force Academy, General Ira Eaker for the Royal Air Force Museum in London, and Lieutenant George Kelly at the main gate of Kelly Air Force Base. From there, I did a sculpture of Winston Churchill in Cambridge, England, The Lincoln-Douglas Debate for Lincoln-Douglas Square in Alton, Illinois, and a series of 17 bronze portrait busts for the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton. About this time, Father Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, asked me to do the sculpture of his dear friend, the late Rev. Charles E. Sheedy,CSC, for O’Shaughnessy Hall.

The dream comes true

It was not until 1993 that I finally got the opportunity to create a sculpture of my idol. While talking to Coach Lou Holtz in his office one day, we discussed the idea of my creating two small bas reliefs of Rockne and George Gipp for the varsity locker room. These were followed by seven additional relief sculptures of Notre Dame’s seven Heisman Trophy Winners. Soon, “Leahy’s Lads” commissioned me to create the heroic sculpture of Coach Frank Leahy outside Notre Dame Stadium. The life size bronze of Edward “Moose” Krause followed shortly thereafter. I was on a roll but the best was yet to come.

Two years ago the City of South Bend and the College Football Hall of Fame decided to honor Knute Rockne by placing a larger-than-life size sculpture outside the Hall of Fame. City officials considered Rockne to be the most illustrious South Bend citizen of the 20th century, while the Hall of Fame judged Rockne to be one of the greatest, if not the greatest football coach of all time (certainly his .881 winning percentage—the all-time best for college and professional coaches—helps prove the point).

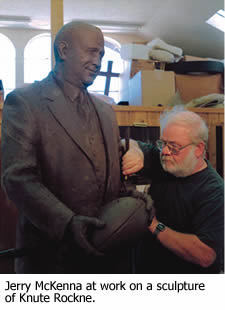

A life-long dream came true in 2002 when I was commissioned to create this, the definitive Rockne. sculpture. After many discussions with the sculpture committee, it was decided that I would portray Rockne in a three-piece business suit, holding a football, rather than wearing coaching togs. Also, I wanted Rockne to look the way I had envisioned him since I was a young boy, warm and approachable. Once the maquette was approved by the committee, I started to work day and night on this labor of love. Over the next 18 months with the use of hundreds of photos of Rockne provided by Charles Lamb, University archivist, and John Heisler, assistant sports information director, the sculpture began to take shape in my Texas studio. Bernie Kish of the College Football Hall of Fame and numerous Notre Dame alumni were able to critique the sculpture as the work drew to completion.

While working alone in my studio one night I came upon an idea that would inject even more life into the sculpture once it was cast in bronze. Bronze is composed of 95 percent copper, 4 percent magnesium, and 1 percent silicone metals. However, I decided that it might be possible to add some metals to the mix that would reflect Rockne’s birth, his life and his death in a special way. I would add three metals to the bronze to represent these various phases of his life. From Voss, Norway I obtained some steel parts from a carriage made by Knute’s father, Lars Rokne (the “c” was added when the family arrived in America), in 1888—the year of his birth. From Chuck Lennon at the Alumni Office, I received some gold leaf from the Golden Dome to represent Rockne’s life at Notre Dame. And from the Cottonwood Falls (Kansas) Museum, I got some scraps of aluminum from the doomed aircraft to symbolize his death in l931. Moments before the sculpture was cast I carefully dropped these extra components into the crucible of molten bronze.

After the sculpture was cast, welded together, refined and patinated, I loaded it onto my old pickup truck and drove the 2,000 miles north to South Bend. There, on a cold and rainy March 19, 2005, it was unveiled at the College Football Hall of Fame in front of Rock’s son, Jack, and his grandchildren, Nils, Anne and Knute Rockne III. At last, I had been able to play a part in honoring the man I had admired all of my life.

But the story does not end there. After the unveiling at the Hall of Fame I obtained permission from South Bend officials to cast a second bronze of the Rockne from the same mold. I then traveled to Rock’s birthplace and offered this identical sculpture to the town of Voss, Norway. They had long been planning to honor their most famous native son but had been unable to raise sufficient funds for the project. When they heard my offer, they readily accepted. A press conference was arranged, and I had the pleasure of announcing the gift in a broadcast heard by an estimated two million Norwegians. During that brief visit to Voss, my wife, Gail, and I were treated to a ride in Lars Rokne’s 1888 horse carriage and a drive in a 1931 Studebaker “Rockne” automobile presently owned by one of Knute’s Norwegian cousins. The Voss town council also settled on the date for the dedication. On March 31, 2006—at the exact moment his plane crashed on a lonely Kansas hillside 75 years earlier—the sculpture of Rockne was unveiled at the site of his birth.

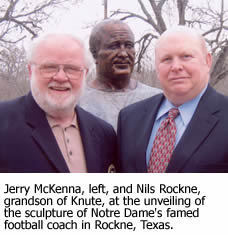

Three other Rockne sculptures will be dedicated in 2006. I have created a larger than life-size bronze bust of Rockne that will be placed at three sites. One will go to a small park off Rockne Boulevard in South Bend on the very street that Rockne traveled each day on his way to the campus from his home on East Wayne Street. Another will stand in the new Guglielmino Athletic Center and a third was unveiled on March 4, 2006—Rockne’s 118th birthday—at the small Texas town of Rockne, 30 miles east of Austin.

Life takes many strange turns. I started out at Notre Dame as a seminarian and switched to fine arts. I had a lifelong desire to pay tribute to Knute Rockne and originally thought that could be done by writing a book. As my military career came to a close I discovered my gift for sculpture. Now my bronze tributes to Rockne hang in the Notre Dame Stadium locker room, stand in front of the College Football Hall of Fame, grace the site of his birthplace in Norway, an athletic building at Notre Dame, a park in South Bend and in the town of Rockne, Texas. There is no doubt that Knute Rockne influenced my life. I feel honored that I was able to keep his memory alive through my art. For me, there was no better way to remember Rockne.