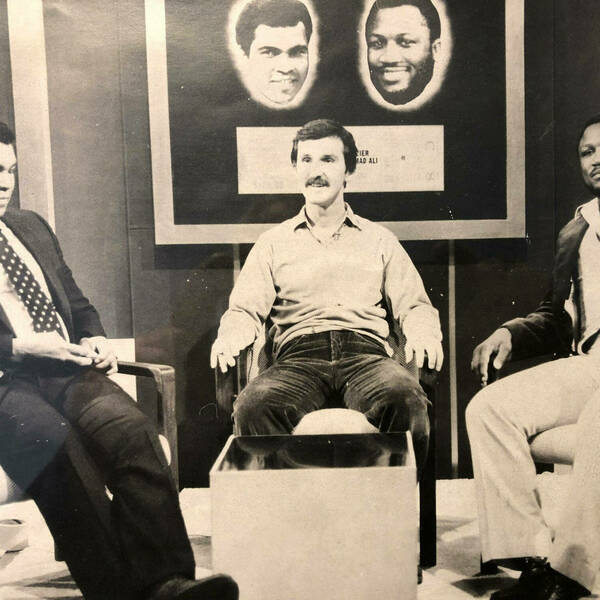

Photos provided

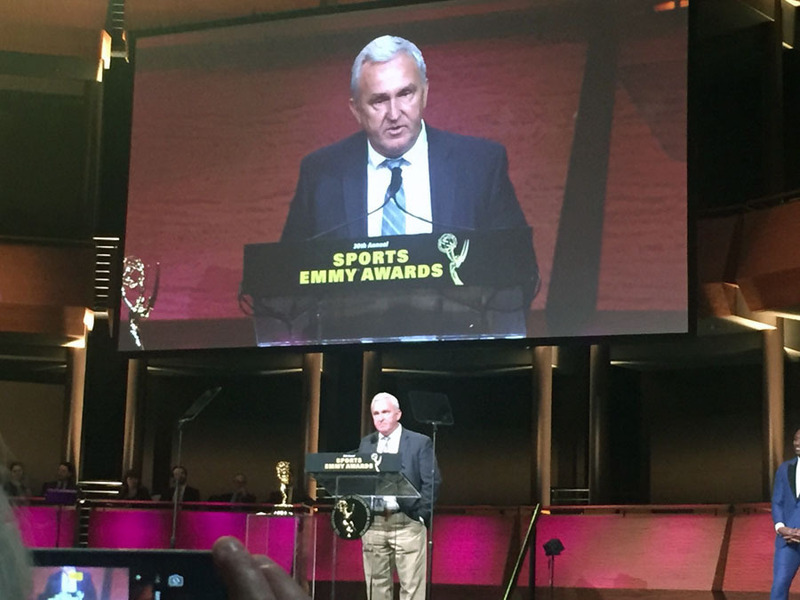

Photos provided

One day in 2012, as Mike Sheehan ’78 and his niece Claire were walking to lunch around 42nd Street and Third Avenue in Manhattan, his phone rang. He glanced down and saw the name Bucky Gunts.

“I got to take this call.”

Gunts, a television legend who had led NBC’s Olympics coverage, told Sheehan he was retiring. The coordinating director job for the Olympics was his, if Sheehan wanted it.

At the time, Sheehan directed Football Night in America, NBC’s Sunday primetime NFL pregame show. If there’s a bigger and better job than Football Night in sports broadcasting, Gunts had just offered it to him. It didn’t take Sheehan as long as this sentence to say yes.

After 10 years, he’s directed coverage of four Olympic opening ceremonies and has to count on his fingers to tally that he’s worked six, seven, eight Olympic Games overall, with planning for his ninth — Paris 2024 — well underway. Sheehan directs other stuff, too, including the World Cup for Telemundo. He’ll spend Thanksgiving in Qatar overseeing broadcasts as the most-watched athletic event on Earth kicks off.

When a sports presentation calls for storytelling and spectacle beyond the competition itself, “we feel much better with Mike in that director’s chair,” says Joe Gesue, NBC’s senior vice president for Olympics programming. Sheehan’s colleagues point to his uncommon versatility, zooming from wide angle to minuscule nuance and back out again without losing focus.

“He has the ability to both have vision, keeping the big picture of what we’re trying to accomplish in mind,” Gesue says, “and gets into the details like no one I’ve ever seen, on a vast array of things.”

John Barnes ’03, an NBC senior producer who works with Sheehan on the Indianapolis 500, remembers him organizing the performance of a high school marching band for the 2019 prerace show. Instead of a shot of the band performing during the morning racetrack parade, as Barnes suggested, Sheehan arranged with the band leader to have the musicians play on NBC’s set. The viewing audience would never have known the difference, which required far more time to plan than the band’s appearance on screen, but the extra work was worth it. “A really cool moment,” Barnes says. “Takes what I would selfishly call, ‘Oh, a really good idea by me,’ and just puts this flourish on it.”

Those flourishes accumulate and add up to better television.

Sheehan’s creative range is unusual, but not as rare as his demeanor during the often heated moments of concentrated intensity when weeks, months, years of planning come to fruition — or don’t — on live TV. Imagine orders barked without concern for feelings, salted with language that would translate into a bleeping Morse code on the air. That kind of thing is routine in TV production trucks; you just won’t hear it from Sheehan.

“Mike never says anything that’s not nice,” says David Mazza, the chief technical officer for NBC Sports. “Sometimes you have to scratch your head and say, ‘Is that the director? He seems awfully pleasant and respectful.’”

Sheehan exudes a shambling magnanimity, deflecting credit and praise. In this collaborative business, he says, “the only thing one person can do alone is screw something up.”

Barnes first experienced Sheehan’s lack of ego when they worked together more than a decade ago in the early years of Major League Baseball’s TV network. Barely in his 30s at the time, and self conscious about his status relative to his colleague’s illustrious reputation, Barnes recalls studio host Matt Vasgersian saying, “Mike Sheehan, you’re working with Barnes? This is like Picasso using crayons.”

Exactly what it was like, Barnes confirms, but his accomplished colleague was content with a Crayola palette, even excited to see what new color combinations might be possible. “He treats everything as an opportunity rather than an obligation,” Barnes says.

Global sports phenomena like the Olympics and the World Cup require years of preparation to televise. As coordinating director, Sheehan supervises elements like location selection and set design for studio broadcasts, the logistics of camera placement and lighting at multiple venues, relationships with international broadcast partners and far-flung freelancers. To say nothing of navigating diplomatic complications or adapting to fast-changing technology and new media to reach dispersed audiences.

During a long weekend this past May working the Indy 500, parsing plans for the prerace show down to the second with Barnes and many others, Sheehan squeezed in a long conference call about the upcoming World Cup. And that Tuesday after the Sunday race, he flew to Paris for Olympic meetings.

In a way, it’s like preparing to compete. What’s on TV reflects years — entire careers — of unseen effort. The pressurized atmosphere of live TV still energizes Sheehan on the last laps of his career like it did when he was a student runner for Notre Dame football broadcasts. He never considered another path. “There’s an adrenaline rush that you get like no other,” he says.

Sheehan occupies an exalted position now, ensconced as a network staff member with 18 sports Emmys to his credit, a boldfaced name in his behind-the-scenes profession. He built his reputation in the usual way that TV sports production careers developed back in the day — as a freelancer doing a little bit of everything for a lot of clients.

For years he did camera work, graphics, stage managing. A regular client was HBO, offering frequent assignments on championship boxing broadcasts, Wimbledon tennis coverage and the football studio show Inside the NFL.

To nudge himself up the ranks, he’d offer to direct, telling companies not to pay him if they didn’t like the result. “Fortunately, I never got anybody who took me up on that,” Sheehan says.

One of his first directing breaks was a 1990 Syracuse-Connecticut men’s basketball game in the heyday of the old Big East. As popular as the sport was, the broadcast was modest compared to what Sheehan sacrificed — leading graphics for HBO on the Mike Tyson-Buster Douglas heavyweight championship fight in Tokyo.

When Douglas registered one of the greatest upsets in sports history, friends on the crew in Japan teased Sheehan for missing the moment. “That would have been a fun, memorable story,” he says, “but I never regretted giving that up to go from working as a tech to being able to direct basketball.”

Regrets of any kind elude Sheehan — even after two-plus years of pandemic interference and uncertainty that made broadcasts of the postponed Tokyo and restricted Beijing Olympics the hardest of his career. There’s no mistaking the genuine joy the job gives him, but the easygoing exterior belies his emotional investment.

“Actually, he worries me,” NBC’s Mazza says, “because he puts heart and soul into the thing.”

Just how much became evident near the end of the 2022 Beijing Winter Games. A closing montage showcasing the highs and lows, set to a swelling movie score, provided a moving coda to weeks of competition. Each time the video played in the control room, Mazza noticed that Sheehan took off his headset and left.

“I think he didn’t want us to see the tears rolling down his face.”

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.