When I was 8 years old, my mother insisted I take piano lessons. I liked the lessons until I didn’t, and when, at age 10, I quit, my mother accused me of lacking “stick-to-itiveness.” She was right. I didn’t have stick-to-itiveness. I preferred reading comic books and watching television to pretty much anything that I was supposed to do that required dogged determination and patience.

Then one day I found myself with a big old house in Baton Rouge, a husband, three midsize kids, a minivan, a published book, and a beat-up honky-tonk piano in the corner of the playroom that no one played, and decided that rather than have the thing go to waste, I’d pick up where I’d left off more than 30 years earlier and learn to play it.

This time, propelled by decades of self-discipline, I persisted, eventually upgrading to a baby grand on which I slowly achieved a sense of competence. The kids grew up. I grew gray. I kept going and had been going at it for almost 20 years when my piano teacher, Tom, suggested I take on the first of Brahms’ Three Intermezzi for piano, Op. 117. The composition is exacting, but with Tom’s assurance that I had what it took to play it, I started in.

Pensive, melancholic, moody, smoldering, introspective — heaps of fat adjectives have been deployed to describe the work, including Clara Schumann’s ecstatic declaration that “in these pieces I at last feel musical life stir once again in my soul.” Me, not so much. And not because I’m not moved by music. When, in college, my friend Scott Martin, himself a jazz pianist, took me to hear Les McCann and Eddie Harris play at a club on the Boston side of the Longfellow Bridge, it was as if I’d personally met God. To this day, every time I listen to a recording of “Compared to What” I dissolve into a pool of pure longing.

But with the intermezzi, which Brahms himself is said to have called “the lullaby of all my grief,” I was on my knees. I couldn’t get my fingers to hit the notes, and when I finally managed that, my hands hurt. The timing was tricky, and it didn’t help that though I read musical notation, I’m iffy at best when it comes to the niceties of time signatures, let alone dotted eighth notes. (Don’t ask.) The first 20 measures, comprising the opening movement, are filled with intimidating leaps, and no matter how often and repetitiously I worked on them, my hands landed like lemmings. In time, I began to hate not just the composition but the piano itself, so much so that I was afraid that the very playing of the piano had become an empty exercise. Which could only mean that I was heading off the cliff, returning to the place I occupied as a child.

Forty some years earlier, when my mother insisted that I lacked stick-to-itiveness, the accusation stuck. Of course it stuck. By the time I was 10 I was swallowed up in a depression so thick and so viscous that I could barely breathe and was convinced that I could never be anything other than inadequate. Then I grew up and discovered that I didn’t lack stick-to-itiveness, but rather that the depression I’d labored under had sucked anything resembling motivation from my internal storehouse. Also, if it was something I didn’t care about, I didn’t bother with it. (Who needs multiplication tables, or for that matter, the persnickety rules of grammar?)

What did I care about? I cared about words; I cared about language; I cared about art; I cared about books; and I cared passionately about writing. It is and for years has been my central preoccupation, the thing that I can’t not do. It not only gave me a reason to persist but became the focus of all my dreams and aspirations. It’s where I locate myself, where I feel solid, purposeful, alive. But it’s a long game. You have to keep at it, and keep at it again, battling your own inner naysayers, the whims of fashion and whoever told you that you aren’t good enough, that you’re never going to make it, that it’s dangerous to dream big. Not to mention the rejections.

Speaking of rejections, for years I was as terrible a writer as most beginner writers are and was no doubt worse than many. What did I gain for my troubles? Rejections. By the bucketful. I stuck with it anyway, enduring what at this point adds up literally to thousands of rejections. Rejections from literary magazines. Rejections from newspapers. Rejections from agents. Rejections from book editors. These days most of them arrive in the form of email, though they used to come on preprinted rejection slips of the kind I myself sent in droves during my first job as a schlepper at now-defunct Mademoiselle magazine. Home to such luminaries in their day as Sylvia Plath and Truman Capote, though, by the time I arrived at my cubby on the 11th floor of the Condé Nast building, no more.

God I hated it there. I was so out of place. Also, I was bad at my job. I wanted to write stories of literary merit, not popular advice about bra sizes or makeup, or even the article called “Blonde for a Day” that represented the peak of my women’s magazine career and came to me by default because the freelancer who’d been given the assignment kept mashing it into a diatribe about the misogynistic trappings of the patriarchy. Would I please transform myself from my naturally dark (read: Jewish) self to a shining, bright (read: makeup and wig) blonde, go out into the world as a shining blonde bombshell, and then compose something suitably frothy?

Like the understudy who wows the audience to such a degree that her career is launched, I jumped on it. For the next two or three days, I was high on the glory. Then I faded back into the monotony and invisibility that comprised my usual abode, bored senseless over a pile of poorly written manuscripts and sending them back to their authors with preprinted rejection slips:

The Editors of Mademoiselle appreciate the chance to consider your work. We regret that the enclosed submission does not meet our needs at this time.

How many thousands of these did I sent out, sometimes with a little handwritten note — enjoyed! or thanks for thinking of us! — often without anything but revulsion for both my job and the horrendously awful writing that comprised the “slush pile”? True, my own work was terrible, but at least I knew it. I knew it because when I wasn’t writing embarrassingly awful short stories, I was reading extremely excellent books.

I never wanted to write popular page-turners along the lines of Sophie Kinsella, author of the Shopaholic series, or the mega-bestselling John Grisham. And though I hoped my not-yet-written books would sell, hopefully in big numbers, my soul yearned for nothing less than to be the vessel of art. But everyone I was close to thought I was thoroughly self-deluded. As in: Who do you think you are? The corollary being I told you so. As the rejection slips piled up, I began to think of myself as a repository of I told you so. It was almost like a secret and shameful habit I had, this compulsion to write, which, for me, came with the need to keep it secret.

I would bet money that most if not all students in MFA creative writing programs pursue their degree with the aim of — eventually — writing a masterpiece. Even those who end up writing mommy blogs or decide to go to law school. I know I did, and without this conviction — that somehow, along the way, I’d both hit my stride and find an audience — I would have given up before I even started. For one thing: What are the odds? For another: Who did I think I was? Hint: a nice Jewish girl from a wealthy Jewish family, with an inner world so constricted that it’s a miracle I could breathe, a good-but-not-great academic record and a reputation within my large and ambitious family for lacking stick-to-itiveness.

I was young, and now I’m not. I still, however, want to be the vessel not of entertainment but of art. A masterpiece or two, even little ones, would be nice. I dreamed of the day I’d find an audience and become, if not beloved, then at least a known element, my name recognized at parties, friends-of-friends impressed. To me, fame has always been the holy grail, the magic elixir that will finally turn me from a nobody into a somebody. Who do you think you are? If I ever achieved it, though, I wouldn’t be satisfied, because like all addicts, even those among us who are merely addicted to the illusion that some thing or set of conditions out there will finally bring us to peace, enough is never enough.

Long before my mother began to grapple with the cancer that eventually killed her when she was 71, she started apologizing to me for the mistakes she’d made raising me, including how she’d handled my rejection of the piano. (Now that I’m the age I am I can honestly say that I, too, may have made a parenting mistake or two.) After her cancer diagnosis, her apologies became more frequent and more resolute. Years of suffering, treatment, remission and more treatment followed, and with them, my mother’s need to go back over things that had or hadn’t happened when I was growing up. Ironically, it was just a year before her death that I took up the piano again, and when I proudly played one of Bach’s Anna Magdalenas for her on the Steinway she’d brought from her childhood into her marriage, she told me I’d been right the first time around, when, at the age of 10, I refused to continue my piano lessons.

This time, it didn’t matter. Or at least not a lot. I’d taken up the piano as an adult, with an adult’s conscious determination to give it a go, with no illusions about my abilities but rather an ill-defined desire to add “playing the piano” to my personal CV. And sure, by now I’d produced a couple of books and dozens of essays and short stories, not to mention three children. But it wasn’t enough. I had to connect the dots, fill in the holes. I’d spent most of my adult life in the pursuit of just those achievements that my twisted and brittle and broken little heart thought just might put me over the top — but it still hadn’t worked. Thus, the piano.

The first of these Brahms intermezzi starts out with lyrical, lullabylike intonations and then grows dark and mean before, in its second bit, it switches from the key of E flat major into B flat minor (all black notes except F) and proceeds to jump up and down the keyboard like an Olympic figure skater. The third and concluding bit returns to the lulling and melodic theme introduced in the first part, only now Brahms has developed the theme with all kinds of flourishes and splits the melody between the right and left hand.

I can no more imagine my life without writing than I can imagine my life without God. I don’t mean to be grandiose. It’s just how I experience the work that I do.

At what point did I become aware that the piece was breaking me, sending me into an emotional crisis that involved all my ancient feelings of unworthiness? Four months in? Five? I can’t remember exactly, although I do remember the earnest discipline I brought to my daily practice: doing it hands separately, hands together, as block chords, with the metronome, with the “time trainer speeder upper” app on my phone, using the inverted triangle technique, using the eyes-closed-hands-exploring technique, awarding myself with pennies (for each measure played without an error until I accumulated five pennies, at which point I could move on to the next phrase), rewarding myself with Scotch, rewarding myself with chocolate, feeling the heaviness of my hands, being aware of pushing the keys all the way into their beds, envisioning movements from one note to the next as choreography, and praying to God, should it be his desire for me, that I learn to play the damn thing.

The thing is, I never deluded myself into thinking that I had anything more than a bissel of musical ability, and not for one second did I envision myself playing the piano in front of an audience more substantial than my dogs. Long before I met Brahms, I knew I’d never be nearly as invested in playing the piano as I was in writing. Even so, I just couldn’t conceive how I might free myself from Brahms without becoming the girl who lacked stick-to-itiveness, a disappointment and a joke.

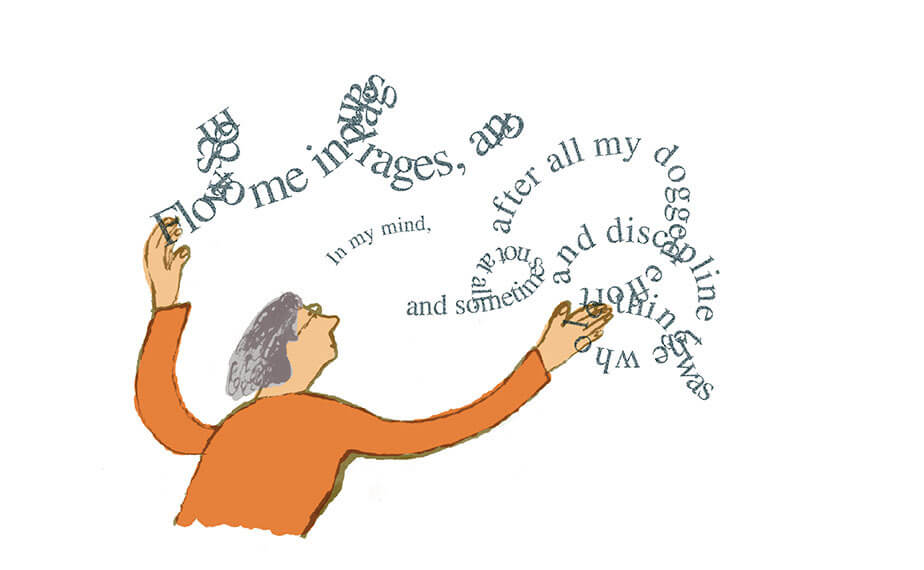

I was also beginning to hate Tom, because even though he would never pressure me into working on something I didn’t want to play, in my childlike conviction that I need to please the grownups in the room so I can earn praise and so avoid the shame of Who do you think you are?, I continued working on Intermezzo No. 1 even as it filled me with despair. In my mind, if I quit Brahms, it meant the failure of the entire enterprise. I was seized by dread and wondering if my 20 years at the piano were, in the end, a joke. That after all my dogged effort and discipline the whole thing was turning out to be nothing but a giant Ponzi scheme.

When I finally told Tom I was all but broken, he assured me that the exercise, though frustrating, had lifted me to a higher pianistic level. Maybe. But at least the fever had subsided, and while I was still wobbly, I was no longer sick. How important is it for me — or anyone — to be good at something that is neither a calling nor a professional goal? Or to put it another way, is it OK for me to be merely OK, a hobbyist, an amateur enthusiast?

I’m in my 60s. You’d think that if “it” was going to happen, it would have happened by now. Time is running out: How many more years might I still have something in me that needs to be let out onto the page? Even the greatest writers tend to lose power as they age, and here I’m thinking in particular of Philip Roth, writer of genius, whose last few novels were meh at best. V.S. Naipaul. Doris Lessing. Alice McDermott. Vladimir Nabokov. We can argue about whose work is truly great and whose is merely wonderful, but the point remains that when the gig is up, it’s up. Dancers, who rely on their bodies to perform all those astonishing leaps and pirouettes, know this. Writers not so much.

Somewhere I read: “Whatever is worth doing is worth doing badly.” I love this aphorism so much that I wrote it down and taped it to the wall above my computer, so that each day as I sit down to write, I’m reminded that the making of all art, be it playing the piano or writing a novel is slow, painstaking, messy, frustrating and sometimes drearily boring work. I put years — decades — into it. Finally I learned how to write. When it’s going well, it’s because I’m in flow.

Flow is something Tom and I talk about a lot. As a teacher, Tom’s all about flow. Not that it just comes to you, a gift from the gods. It has to be slowly and painstakingly won. But what a prize it is when it comes, what quiet ecstasy to be so entirely subsumed in the work you’re doing that the “I” vanishes.

There’s this great scene in the third of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, when the narrator, a budding novelist, finally gets the babysitting help she needs to write her second book, only to experience first the misery of writer’s block — the exact opposite of flow — then the ecstasy of inspiration, and finally the despair of interior collapse when both her editor and her best friend declare the work subpar. In the film version (which I’ve been watching on HBO with my husband), the scene is played out primarily by a look of quiet horror on the character’s face. I know that feeling. It’s been the backdrop of my entire life.

Flow comes to me in rags and rages, and sometimes not at all. It depends on what I’m working on. In general, shorter pieces — essays, short stories — come to me in one rushing whoosh, as if my job is merely to get the words that are already there onto paper. Too bad for me that after poetry, short stories are probably the most difficult form to publish. My own agent has told me that no one reads short stories anymore, as if I didn’t already know that. Novels are more a matter of pushing big rocks up long hills, only to find them tumbling down again until, a decade or so later, they stop falling back down the hill. I keep writing anyway. It’s the thing I love doing above all others. I truly believe that the urge to write was given to me, an assignment from God, that to the degree that words — and more to the point, stories — might pierce a heart or inspire a hope, perhaps mine might, too. After all, I don’t write them all by myself, but always — always — with something like a holy spirit sitting on my shoulder, whispering, Grow, grow! I can no more imagine my life without writing than I can imagine my life without God. I don’t mean to be grandiose. It’s just how I experience the work that I do.

Not so with the piano, where I started out and always will be an amateur. Finally, in the wake of Brahms, I have made my peace with that. I keep playing anyway, because after 20 years, playing the piano has become part of my day, on good days a meditative break from my “real” work, and on bad days more like a chore, done in the spirit of getting-it-over-with-already. As often as not I wonder what my mother, gone now almost 20 years, would think if she could hear me play. Her photograph sits on my piano, and every time I sit before the keys, she gazes out at me, her eyes dark and expressive, her expression slightly bemused. In life, she loved me, and told me so in ways large and small. But in death she never says a word.

Jennifer Anne Moses is the author of eight books, most recently The Man Who Loved His Wife, a short story collection. Find her at www.jenniferannemosesarts.com.