The Arecibo Observatory’s radio telescope, for decades the world’s largest, collapsed this month. Image via Shutterstock

The Arecibo Observatory’s radio telescope, for decades the world’s largest, collapsed this month. Image via Shutterstock

When the epic radio telescope at Arecibo, Puerto Rico, gave up the ghost on December 1 — literally falling to pieces as its skeletal instrumentation platform brought almost 1,000 tons of steel crashing down 500 feet through its 19-acre reflector dish — I felt a sense of personal loss.

The death of that revered astronomical instrument, storied for probing the far reaches of the universe, made me more aware than ever that my own story is in its final chapters. And, for some moments, I reflected on words I’ve written and pages I’ve turned to get here.

Since I wore a younger man’s clothes, I have felt an abiding connection to that radio telescope — until 2016 the world’s biggest, its dish of aluminum panels, 1,000 feet across, supported by steel mesh cradled in a sinkhole of Arecibo’s classic karst landscape, sculpted by the dissolution and erosion of limestone.

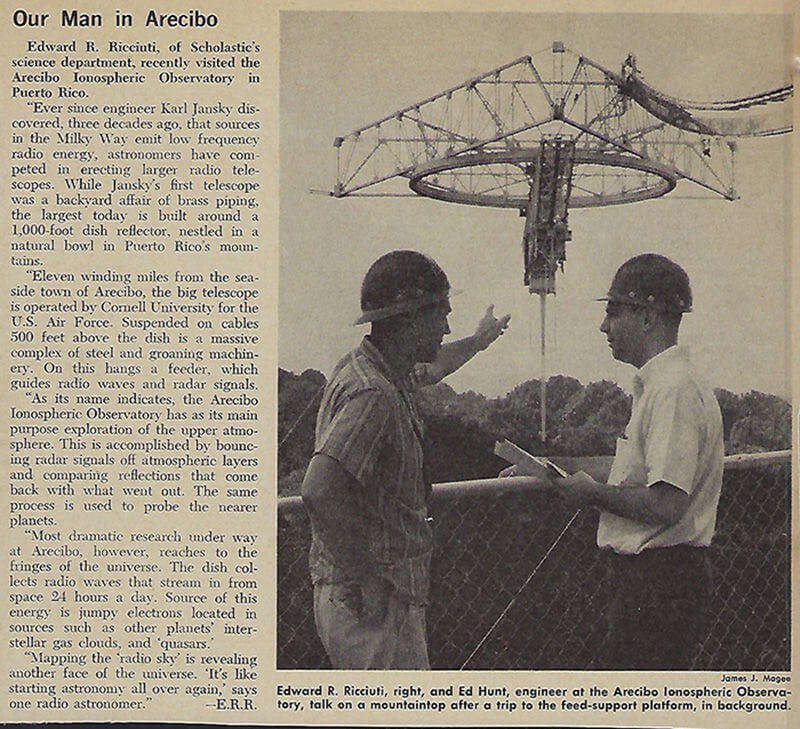

Arecibo’s telescope and my career as a journalist and writer were both spanking new when, in the middle of another century, I stood on that platform, looking out over mountaintops covered with deep green tropical forest to a sparkling blue sea in the distance. Arecibo was then the talk of the scientific world, only two years old when I arrived to write about it for Science World magazine in 1965. I only half realized it at the time, but that visit marked a pivotal moment in both my life and my career, leaving Arecibo etched in my memory.

After I saw the news that the telescope had collapsed — battered by age, earthquakes and hurricanes — I went to a file drawer in my home office and took out the article I had written, which billed me, with admitted overkill, as “Our Man in Arecibo.” I was struck by how back then I had to explain to readers “What is a radio telescope?” Radio astronomy was in in its infancy, just three decades old and a mystery to many. I had to explain the nature of the “radio universe” and how scientists use radio waves to map it, hardly necessary for even elementary school kids today.

What impacted me more profoundly as I read my words was the naïve sense of wonder in the way I described my virginal visit to the tropics:

Night in the mountains of Puerto Rico — darkness so thick and velvety you feel as if you could grab a handful of it. Heavy air vibrant with the trilling of thousands of tree frogs. Tangles of black vegetation astir with the scuttlings of night creatures. Moonlight gleaming on limestone cliffs.

Through this living darkness a jeep — with me perched in its back seat — shuddered up a rutted track. The dirt road snaked up a hillside, flirting with the edges of inky ravines. But the driver, Jack Burry, jockeyed the jeep around potholes like a New York City cab driver.

Not all that bad, I thought, but a bit overplayed by a young writer gripped by excitement born of something new to him, but which was just an everyday walk down the block to people who worked there and lived nearby.

I was reminded of another experience, later in my career, when I had hiked up a ridge above a Peruvian police post in the Andean Altiplano, which I was using as a base on assignment. I felt like quite the explorer, standing at about 15,000 feet, watching an Andean condor sail by, stark white and black against the crystalline blue sky. Until, that is, I saw a little kid traversing the same trail, back and forth each day to school. Later, I found a blue marble he apparently had dropped along the way.

That episode was some years after my visit to Arecibo. I had arrived in Puerto Rico after hopping a plane from St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, where I had disembarked from a week on the first nuclear aircraft carrier, the U.S.S. Enterprise. I had been assigned to write about the carrier undergoing its operational readiness inspection before heading for the conflict in Vietnam. I loved every minute of it, especially because I was assigned officer’s quarters and the use of the ward room, which would have been assuredly off-limits when I served as a lance corporal in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve.

The two-part assignment was my first outside the continental United States and I marveled that it was happening to me. As I stood on the platform at Arecibo, accessible by a shaky aerial catwalk and a swaying cable car, I felt euphoric; here was I, only a couple of years removed from reporting on school boards and police stations in New York City’s suburbs, covering a story in an exotic locale, not as a tourist but actually getting paid to be there.

It was then it occurred to me that I would like more of the same, lots of the same. It took a few years but, having taken a chance on full-time freelancing, what was a dream at Arecibo came true. I had been behind the Iron Curtain. I was practically commuting to Africa, hearing lions roar in the night. I watched a tiger prowl near sambar deer in Thailand. Roping down the cliffs of Tatoosh Island at the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, then heading into the Andes only a week later was a bit hectic, perhaps, but becoming commonplace. Magazines and conservation organizations and a government or two were paying the freight.

I was by no means a foreign correspondent, but for more than two decades I was abroad several times a year, often to the world’s backwaters at exciting times: Iran just before the revolution, Yugoslavia before and during the war, South Africa during the transition from apartheid. It took some work and a little luck to nab those assignments but I got pretty good at it.

I often wonder if I would have fired up sufficient drive to engineer the career I never anticipated had it not been for that visit to Arecibo and the taste of what, at the time, felt like reporting from a faraway place.

I never visited Arecibo again. Puerto Rico? Many times. My wife has deep roots there on her maternal side. Her grandfather was a business partner of Teddy Roosevelt III, who served as governor of Puerto Rico. Her mother headed diplomatic protocol for the commonwealth government for several years. With our children, we often visited the island and I wrote several articles about it. A few times, I passed through the karst country, near Arecibo but never off the beaten path to see it again. Figured that, sooner or later, I’d do it.

I didn’t, and I regret it.

Ed Ricciuti has been reporting and writing for 60 years and teaches martial arts near his home in Killingworth, Connecticut.