Late in the fall of his senior year at Notre Dame, John Kohne made a big mistake.

Imagine that. He was 21, a kid at college like how many others, thinking about his studies and his future, wondering if he’d become a part of the problems he saw hurting humanity or somehow a part of their elusive solutions. And rather than contrive some purely symbolic gesture or waste a lot of time in talk or protest, he had decided to take control of a part of his life that was his alone to determine.

He dropped out of school. Twelve credits shy of graduation, the chemical engineering major decided that he couldn’t take his place in an industry he believed could do no good in society. The time had come, he felt in that moment, to leave Notre Dame.

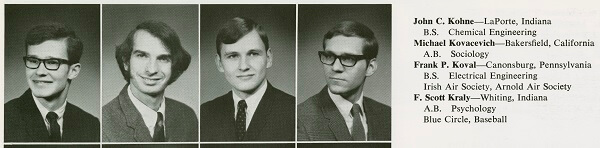

At yearbook photo time in 1969, John Kohne was still planning to walk with the Class of 1970. Courtesy of University of Notre Dame Archives.

At yearbook photo time in 1969, John Kohne was still planning to walk with the Class of 1970. Courtesy of University of Notre Dame Archives.

Time to face a Christmas without a spring semester to follow. Time to face his parents, the local draft board and a war he refused to fight. Time to find a path forward that he felt would allow him, if nothing else, a chance to live his life without doing others harm.

It was 1969, the height of the Vietnam War. Dow Chemical recruiters, their company weathering years of blistering protests for their manufacture of the incendiary, skin-adhesive chemical jelly known as napalm B, had conducted job interviews in the Main Building the previous spring. To Kohne, and to many other students across the country that fall, it didn’t matter that Dow had lost its contract with the U.S. military earlier that year. Its sins — and the sins of other entities in the chemical wing of the vast military-industrial complex — were committed, and unforgiveable. “Better Living Through Chemistry,” the DuPont slogan that became the midcentury credo of American hopes for science-driven social progress, had soured for young people who had embraced a different kind of social consciousness into a knell of destruction and death. Kohne had neither taken part in the Dow interviews nor participated in the sit-in demonstrations against them. He was no radical. He had simply had lost faith in his field.

So he made the cut, severing ties with Notre Dame, afraid that any less decisive move would mean inevitable compromise: a degree, a job, a salary at the expense of his heart and his conscience. Kohne went home to La Porte, Indiana, 30 miles west of campus, to his father Harold ’49 who had attended Notre Dame on the G.I. Bill, the first person on either side of the family to go to college, and his mother, Patricia, who along with her husband had invested so much happiness in the promise of her son’s Notre Dame degree.

That family dream was not to be. His parents didn’t understand why this son, whom they’d named for brothers of theirs who had died in childhood amidst the cruelty of the Depression, was leaving the school that for them represented what was still good and true about the world.

John Kohne understood almost immediately that he’d made a mistake. He would bear the burden of his parents’ heartbreak for 47 years.

As the years passed, Kohne’s cut became a self-inflicted scar, a constant reminder of a wound that never fully healed — not when Kohne found an acceptable path for himself in medicine, not by marriage or parenthood, not by a successful career as a gastroenterologist in Indianapolis that his parents lived to see and appreciate, nor even by his retirement in November 2014 as the chief medical officer of Indiana University Health, one of the most highly rated health care systems in the country.

In fact, retirement made it plain to Dr. John Kohne that his pain still lingered from the choice he made. “It hit even harder that, if I have a bucket list, this is the number one thing,” he said. What would it take to finish his Notre Dame degree?

“How do I say this?” Kohne asks aloud on the Saturday afternoon before Commencement, trying to explain the reason for his return to campus this past spring.

He pauses a while, as rain batters the window of a Grace Hall conference room. Then: “I didn’t come because I wanted to tell this story.”

Notre Dame was never the problem. Even as an undergraduate, Kohne appreciated how the school had broken down his assumptions about the meaning of life and his place in the world, then helped him put it back together, his convictions stronger than before. He admired Father Hesburgh’s engagement with the troubles of the times as well as his handling of overzealous campus activists. But that strength of conviction, that modeling of principle, didn’t mean the young man had found the right answers.

“The Dow thing got kind of caught in wrong thinking in a way for me,” he says. “I can’t say I thought it through very well.”

At home in La Porte, arguments over the war flared, even as the feeling sank in that he’d let his parents down “horribly.” Determined not to go to Vietnam, Kohne escaped that confrontation when his draft number proved to be four above the cutoff. Free to move on with his life, he completed a teaching course at Indiana University’s South Bend campus — had Notre Dame offered a teaching degree in those days, he says, “I might have considered coming back for that” — then joined up with a group of Notre Dame friends headed for Boston after graduation.

Teaching didn’t take. Hired part-time for an experimental school program combining kids from different backgrounds, he soon discovered that the chemistry the kids wanted to learn wasn’t the kind he was teaching. But when a roommate’s girlfriend invited him to sit in on some of her medical school classes at Tufts, something clicked. Medicine promised the social relevance and person-to-person qualities he wanted, plus it would challenge his brain the way engineering had. He raced to take the MCATs, applied to medical schools and wound up back home again in Indiana the following fall.

Ironically, his studies brought him back to Notre Dame in 1973, tantalizingly close to healing the cut. Indiana University had just opened a medical campus in South Bend, and Kohne was soon taking classes in Haggar Hall and watching a second football national championship season in person — but that would be the limit of his brief re-acquaintance with campus life.

All the old feelings came back: “I’ve spent all my time here, I love the place, all my friends and everything I’ve learned that I value has really been learned here.” He paid a visit to the Holy Cross priest who ran the pre-medicine program to ask whether Notre Dame might honor his IU courses. The answer came back, simple and clear. And devastating.

No.

“I had made my attempt, but it just eats at you. I kept convincing myself, telling myself, ‘It doesn’t matter that much that you aren’t an alumnus. You went there, you’ve got great friends, you’ve got a great experience.’”

Play. Rewind. Repeat ad nauseam. As another 40-some years went by.

How do we describe the tough decisions we make in life, later on, when some things work out and others don’t and we’re sifting through those consequences? Maybe it’s mincing words to call the choice John Kohne made in 1969 a mistake, and then to question whether it was a mistake or a calling or something else entirely. The long ache he and his parents carried with them, each for their own reasons, was certainly real. And yet, when asked on the eve of the graduation of the Class of 2017 what advice he would offer the graduates, this gray-haired physician, the “Moonlight” Graham of chemical engineers, looks back with a deeper point of view: “I don’t regret what I did because I listened to my heart, he says. The right things happened in my life because I did, even though they didn’t seem like the right thing at the time.”

It helps, of course, to get a second chance, even if it doesn’t come your way for half a century.

What would it take? The question Kohne had asked the priest in charge of the pre-med program in 1973 never went away, no matter how the answer resounded in his heart. Soon after his retirement, it surfaced once more in a conversation with his old roommate and lifelong friend John Cox ’70, ’74 M.S., an environmental technology consultant who often returns to ND engineering classrooms as a guest lecturer. Cox put the question to the engineering dean, Peter Kilpatrick, who agreed to meet Kohne for lunch.

Stunned, happy, Kohne looked up Kilpatrick online to see what he could learn before they met. He came across a video of a lecture the University of Minnesota-trained chemical engineer had delivered on engineering’s seminal contributions to human progress. It was a little salve on the old scar and he told Kilpatrick at lunch about the impact the talk had on him.

Kilpatrick was receptive, a quantum leap beyond the barrier Kohne had crashed into all those years before, but there were plenty of concerns. A few things had changed since the slide-rule days of Kohne’s undergraduate training, from core scientific advances to the evolution of computers. The older Kohne struggled enough with Microsoft Office programs. What chance would he stand with engineering software — not to mention the updated curriculum?

Kilpatrick turned Kohne over to Cathy Pieronek ’84, ’95J.D., then an associate dean, who ran with Kilpatrick’s encouraging spirit and Kohne’s reawakening hope. Pieronek had nearly lined up everything for Kohne’s re-enrollment when she died unexpectedly in April 2015. Having lost his advocate, Kohne was ready to let the idea drop. But Pieronek, the generous and impeccably organized administrator in charge of the college’s academic affairs, had left behind a file so detailed and clear that her successor, Mike Ryan ’85, could pick up his cause immediately.

In fact, things happened so fast that Kohne found himself asking to defer admission for a year so he could get himself ready. He retreated into the study in his Indianapolis home and read science for hours every day. His wife, Cathy, a retired nurse, “was ready to kill me,” he admits, noting that this was only the first of the sacrifices she would make to help him reach his goal. He took a summer school art class to meet a humanities requirement, then made arrangements to become a Notre Dame student one more time.

Before classes began in January 2017, he decided to pay his professors a visit, just to make sure there weren’t any missed signals or other surprises before he turned up in their classrooms.

“The look you get when you say, ‘I’m taking your class’ — it’s priceless,” he says.

As the shock wore off, though, the new kid and his professors talked their way toward human connections that made everyone more comfortable. One told him she could relate to his life story because of her own decision to leave her native country. Another had worked in the private sector with a dear friend and ND roommate of Kohne’s who had died in a car accident. The third professor’s son had played hockey with the young man dating Kohne’s daughter.

Kohne walked into classes that first week with the reassurance most new students only dream of. This is going to be okay.

He got stares in the engineering library. What’s the professor doing here? Doesn’t he have an office? He struggled to keep pace in courses on Process Design, Process Control and a junior-year lab that somehow he’d missed 50 years before. He went to bed late, got up early, ate when he could and found no time for anything else. He gave up on commuting from Indianapolis, living in a friend’s vacation condo and staying in South Bend even on the weekends he’d planned to go home.

Naturally, the classroom ice broke fairly quickly. Project work forced him to make common cause with students young enough to be his grandchildren. They had a lot to offer with their far sharper working knowledge of chemistry and the principles of engineering. But Kohne found that he, too, had plenty to share: life lessons, vast professional experience and disciplined habits of thought that began rubbing off on his new peers. His project team in the “controls” class played off his love of sailing, designing a system that could navigate a sailboat on its own.

The semester whipped by, a sprint of hard work and self-doubt. Halfway through April, Kohne wasn’t sure he would pass. This wasn’t cheap modesty. “I just couldn’t learn it fast enough, and that was probably the thing that got me most — I can’t master this.” It ate at him whenever he left test questions unanswered as time expired.

Somehow — through a combination of perseverance and the support of department chairman Ed Maginn and the professors teaching his courses — it all worked out. Really, really well in fact. Kohne’s grades were good enough for him to earn him a Notre Dame degree magna cum laude.

Dr. John Kohne (left) of Indianapolis enters Notre Dame Stadium on May 21 with the rest of the Class of 2017. Photo by Barbara Johnston.

Dr. John Kohne (left) of Indianapolis enters Notre Dame Stadium on May 21 with the rest of the Class of 2017. Photo by Barbara Johnston.

The relief he felt was indescribable. “It’s like it just washed away something,” he says. “Yes, it’s finishing, but it’s more a smoothing over or a healing of something for me that wasn’t complete.”

A few days after his grades came in, the gastroenterologist and brand-new chemical engineer visited 257 Fitzpatrick Hall to thank Kilpatrick for the opportunity he’d given him. “Well, John, you’re one of us now,” came the reply. For Kohne, that means he’s in a better position than before to help Notre Dame researchers like those in the University’s Advanced Diagnostics and Therapeutics initiative connect with potential partners in health care across the state.

Even better, the doctor says he thinks his wife understands him a little better now — about his folks and the cloud that followed him around so long — as they get back to yard work, to their grown daughters, to their friends, to normal. “She is so happy this is over.”

On Commencement morning, May 21, Kohne stood with the rest of the Class of 2017 as Vice President Mike Pence directed the students to turn west toward their families and supporters sitting in Notre Dame Stadium and offer them a round of applause. Kohne’s heart traveled a bit farther in that moment, to a small Indiana town about 30 miles away where, degree in hand, he plans to make a very special visit.

But that wasn’t the last surprise of John Kohne’s life as a Notre Dame student. That afternoon at the department’s degree ceremony inside the Rolfs Sports Recreation Center, John Kohne’s name was read aloud and the proceedings stopped for 30 seconds while he received a standing ovation. Kohne’s wife and daughters were there, as were two of his friends from the Class of 1970, John Cox and Bob Jackson. But no one cheered louder than the students — who’d only known the old doctor during the last semester of their own Notre Dame lives. He hadn’t come back to tell his story, but somehow it got around anyway, forcing itself into dozens of young hearts in ways he admits he does not understand. The tears flowed like a waterfall.

“I will likely hear that applause,” he later said, “nearly every day of my remaining life.”

John Nagy is an associate editor of this magazine.