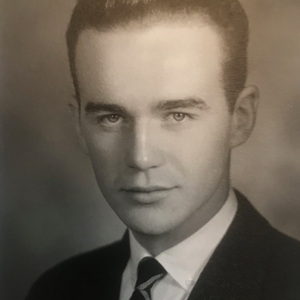

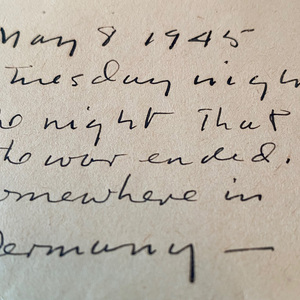

A painting by Bernard Cullen of wartime Germany

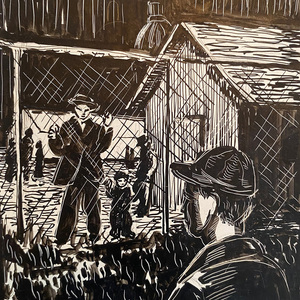

A painting by Bernard Cullen of wartime Germany

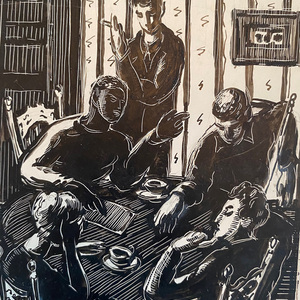

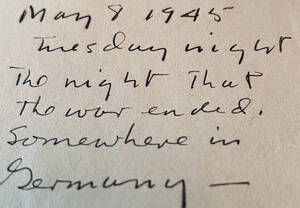

The letter opens, “May 8, 1945. The night that the war ended. Somewhere in Germany,” an ambiguous location to get past U.S. Army censors. To his wife, Bernard Cullen ’38 wrote: “We walked up the road that runs along the hill. We had brought the Eliot along, the Four Quartets, and sat there reading and watching the broad valley and the river wind up around the city. The dead city. Somehow you could tell, but it didn’t look the broken roofless thing it was.”

He went on to say that despite the good news about the end of hostilities in Europe, he and his friends were not celebrating. Members of his battalion were to be sent home for a month, then redeployed to the Pacific.

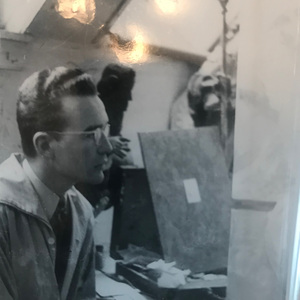

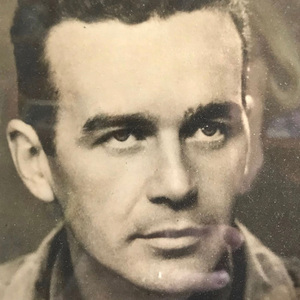

Under occupation on his enlistment card, Cullen — my uncle, known as Bud — was categorized among “artists, sculptors, teachers of art.” In 1943, he had been selected as one of some 1,100 members of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, known as the Ghost Army. Their ranks included painter and sculptor Ellsworth Kelly, fashion designer Bill Blass, and photographer Art Kane, among other future cultural notables.

Few understood what Bud’s unit did during the war and only vaguely for decades after. Official documents weren’t declassified until the 1990s, after the Cold War had ended. More recently, details have been published in several books and in a 2013 documentary called The Ghost Army. Today (March 21) the unit and its few remaining members will receive one of the nation’s highest honors in a Congressional Gold Medal ceremony at the United States Capitol.

The Special Troops had a unique mission: tactical deception. They landed at Normandy in the month following the original June 6, 1944 D-Day invasion. They eventually shadowed Gen. George S. Patton’s army as it advanced toward Germany. His 603rd unit put on a traveling road show using inflatable tanks, sound trucks, fake radio transmissions, scripts and pretense. They staged more than 20 battlefield deceptions, designed to fool the enemy into thinking that battalions had — or hadn’t — advanced into other locations.

Bud never talked much about the experience, but several letters and drawings tell unforgettable stories. One was etched forever in his words and in pictures. On August 27, 1944, he wrote his wife: “So many things have happened in the last few days — I couldn’t really tell you how it was but I can sort of give you our itinerary.” For the previous four nights, Bud had gone to the same bar in rural France with his lieutenant. Possibly he and Lt. Landry were there to spread disinformation. At that point the Allies were poised to enter Paris and there were surely spies and collaborators in the area. Or perhaps they were just waiting for orders.

On the second of those nights — August 25 — the Allies liberated Paris, ending almost five years of German occupation. “(The bar was) well armed with vin and cognac and it turned into some sort of movie scene of the last war — we had Frenchmen sitting with us — Madelon sang us her gentle song and of course I didn’t believe it. The next night we came back . . . a third night and we tried it again.”

The fourth night, he wrote, “was the ‘piece de resistance.’ I can’t quite convince myself that it all happened.” One of the women they were drinking with, named Yvonne, mentioned that her neighbor was a well-known painter in hiding. His name: Georges Rouault. She offered to introduce the young artist to the painter — if Rouault would agree to the meeting.

Rouault assented and Bud wrote: “Lt. Landry and I met George (sic) Rouault the famous Painter — the Maître. He is an old man now . . . he received us very kindly and that was an event because he sees no one.”

“You were lucky to see Master Rouault,” Yvonne affirmed. “You are the only two Americans that he accepted to see.”

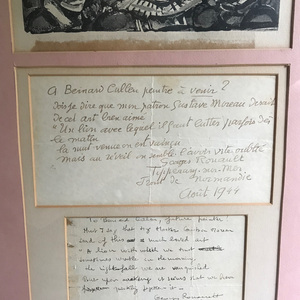

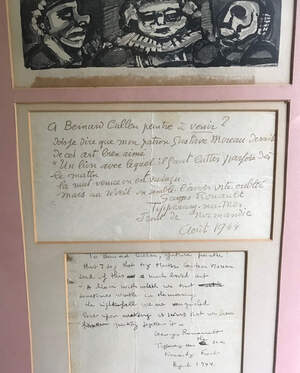

There’s no record of their conversation, but the old Master addressed a note to Bud, enclosing a drawing of some of his signature figures that echo several of his works in the Raclin Murphy Museum of Art collection.

In the note, translated by Lt. Landry, Rouault writes: “To Bernard Cullen, future painter? I have to say that my master Gustav Moreau said of this much-loved art, ‘a lion with which we must sometimes wrestle in the morning. At nightfall we are vanquished. But upon awakening it seems that we have quickly forgotten!’ Georges Rouault, Tipperary on the sea, Normandy Front, August, 1944.” Surely the location made reference to Bud’s Irish ancestry.

The return address on a subsequent letter to Bud, written in January 1945 as the Allies were stalled in Luxembourg, identified the real town where Rouault was in hiding. It was Beaumont-sur-Sarthe, about 140 miles southwest of Paris. Today there is a small museum to Rouault there, and a street has been renamed Rue Rouault.

Bud finally got to Paris sometime after the liberation. The battalion continued to follow the action as the Allies fought their way east. One of his letters refers to the bitter winter of 1944-45 and the snow cover in Metz in northeastern France. They continued their deception during the Battle of the Bulge and when the Allies crossed the Rhine into Germany.

The letter at the beginning of this story, dated May 8, 1945 — VE Day — had been written looking down on Trier, Germany, one of many sites of Displaced Persons Camps. As the fighting receded, the millions who had been made homeless needed a place to go. Some wanted to go home; others didn’t want to be repatriated. Some hid their past. All were hungry. All had suffered trauma.

After the Ghost Army’s last deception in late March 1945, they were ordered to Trier, where they were assigned to guard camps for displaced persons.

It was a sad and sometimes dangerous assignment. Violence broke out in the camp — sometimes between citizens of different countries and sometimes between compatriots — amid accusations of collaboration. In some cases, the camps housed both concentration camp survivors as well as those who had guarded them.

Many of the artists in the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops had sketched throughout their assignments in France, Luxembourg and Germany. Bud brought home artwork he had done toward the end of the battalion’s assignment. Two are painted on what must have been scrap wood. And then there are drawings of the displaced persons camps that tell a story as vividly as words ever could.

In August 1945, when he was back in Chicago on what he thought would be temporary leave after VE Day, the news broke about the bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki, leading to Japan’s surrender. The members of the 603rd Engineering Unit were never redeployed.

After the war, Bud continued studying and teaching art at the Art Institute of Chicago and the American Academy of Art. He gave lectures at DePaul and Loyola universities in Chicago and at Notre Dame. The late Professor Ed Fischer ’37 wrote in his autobiography about his own course in writing, film and design: “I developed the course from one taught by Bernard Cullen, an ND alumnus who used to teach at the Art Institute of Chicago. When I joined the faculty, I took his course and then enlarged upon what I had learned through graduate work in art.”

Bud continued to paint, exhibiting some of his sacred works at the Vatican. He did much portrait work. Ultimately, he took a job in graphic arts with the City of Chicago where he worked for several decades.

He painted less. He struggled for a time with alcohol. I know my father, Bud’s younger brother, was saddened by his frustration and personal difficulties. In the late ’70s he painted two portraits of me. While I treasure them, I sensed his frustration with them.

I wish I had known him better when I reached adulthood. Piecing together a whole person from a previous generation more than 30 years after his death isn’t easy. He was very soft-spoken, gentle and self-effacing. Perhaps art was for him, as Rouault had described, a lion with which we struggle.

How gratifying it would have been to see Bud recognized in the Congressional Gold Medal ceremony for his wartime experience.

Janet Cullen Abowd, a retired French teacher and school administrator, lives in Washington, D.C.