On October 27, 2020, when the political klieg lights switched off and Amy Coney Barrett ’97J.D., former Notre Dame law professor and federal appellate judge, wife and mother of seven, had taken her oath of office and judicial oath and finally sat down in her chambers for the first time as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, she had become several hard-fact things:

The 103rd associate justice of the nation’s highest court, and just the fifth woman to hold that title. The first Notre Dame Law School graduate named to the honor, and the first successful nominee in 27 years to hold a law degree from a university other than Harvard or Yale. (Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, appointed in 1993, started at Harvard but finished at Columbia.) And, as a living barometer of our polarized political moment, the first justice approved without a single vote from the Senate minority. The chilly circumstances of Barrett’s confirmation belied a robust “well qualified” rating from the American Bar Association, the support of the majority of the American people and an on-air affirmation from CNN’s John King that, based on her qualifications, experience and temperament, under normal conditions Barrett “would be getting 70 votes or more in the United States Senate.”

Barrett, 48, is also the youngest of the justices, but that’s typically true of the rookie, and is the first mother of school-aged children to serve in the role — her former boss, the late Justice Antonin Scalia, had young children when he joined the court in 1986.

These are not incidental facts. The legal profession in America arguably regards lineage and pedigree higher than any other. Where you’re from, what you’ve done, who you clerked for: These things matter. So it’s no surprise that, setting aside the 11th-hour tensions of a painfully fractious election season, much was made about the timing of Barrett’s nomination in September coming so close to the death of the judicial titan she would be succeeding.

Flags were then still flying at half-staff across the country in Ginsburg’s memory, a fact Barrett was careful to note in her acceptance speech. “She not only broke glass ceilings, she smashed them,” Barrett said warmly of the former labor lawyer and women’s rights advocate lauded by legions of progressive fans as The Notorious R.B.G. “She was a woman of enormous talent and consequence, and her life of public service serves as an example to us all.”

A point made clear in the weeks that followed was that for many who follow the court, “Ginsburg’s seat” — which counts among its 12 previous occupants a Roe v. Wade dissenter and a justice who left the court to run for president as a Republican — had acquired almost mythic symbolic power. If justices wore numbers on their black robes, Ginsburg’s would surely have been retired. Could her seat be filled with anyone but a disciple of her jurisprudential legacy?

Ginsburg hoped her successor would not be named until after the election. But you can’t deed or retire a seat on the Supreme Court, and October 2020 may be best remembered for the theatrical, partisan fight over whether and how to fill it.

During Justice Barrett’s first day on her rather extraordinary new job, something unwelcome that she had so suddenly become during the confirmation season began to fade away. Quiet and calm, clear-eyed and attentive, Amy Coney Barrett had stood in the middle of that Senate and social-media battle with notable dignity, and now the time had come for her transformation from the realm of contested myth into a more public reality.

For the four-plus weeks of the confirmation process, everyone in America had their chance to write whatever they liked on the professor’s chalkboard. Depending on your lenses, Barrett was a dangerous extremist, a merciless zealot who would impose her beliefs on every hot-button issue from abortion to gun control, a “judicial torpedo” the Republicans couldn’t wait to fire at the Affordable Care Act. . . . Or she was the heroic “Conenator,” an indestructible machine of legal reasoning, America’s last line of defense against liberal judicial activism, proof positive of the viability of big-family motherhood with do-it-all professionalism.

Barrett gave no interviews, avoided social media. Whatever she thought of the overheated rhetoric, pro and con, the caricatures of her religion and personal choices, remains among family and friends. Senators from both parties cherry-picked her legal writings, drew their own conclusions, then addressed their questions and speeches as much to the court of public opinion as to the judge herself. She explained her judicial philosophy and answered personal questions but not policy ones, citing canons of conduct governing her responsibilities as a judge on the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals and the “Ginsburg rule,” which the late justice herself struggled to follow: “no hints, no forecasts, no previews” of anything that might come before her in court.

And so the combative chalk-drawing continued. Friends tried to shade in Barrett’s obscured humanity. “I can assure worried liberals that there is nothing about the prospect of a Justice Barrett that should cause them to fear,” Notre Dame law colleague Carter Snead wrote. Noah Feldman, an old friend and acknowledged ideological adversary, now a Harvard professor who clerked for Justice David Souter during the year Barrett worked for Scalia, offered a conciliatory, pragmatic view. Given the near-certainty of Barrett’s confirmation, he wrote on the day President Donald Trump announced his pick, “it is better for the republic to have a principled, brilliant lawyer on the bench than a weaker candidate. That’s Barrett.”

He continued, “The Supreme Court is best served when justices on all sides of the issues make the strongest possible arguments, and do so in a way that facilitates debate and conversation. . . . And I’m going to be confident that Barrett is going to be a good justice, maybe even a great one — even if I disagree with her all the way.”

The good race

When she was 10 years old, the oldest child in a growing Catholic family in the New Orleans suburb of Metairie, Louisiana, Amy Coney competed in her first track meet.

She lost her event. Seeing her disappointment, an uncle consoled her. “Honey,” he said, “do you know how many times you looked to see where the other runners were? Every time you look to the right or the left, you lose a half-step. Next time, look straight ahead and run your best.”

She told this story 34 years later to students who voted her professor of the year. That afternoon in May 2016, Professor Barrett’s theme wasn’t winning but the danger of comparison. She quoted Teddy Roosevelt: “Comparison is the thief of joy.” Then she shared her uncle’s kindly advice that’s helped her keep perspective along life’s way. It was characteristic of Barrett, regarded by colleagues and students as an exemplary mentor, to use a parting moment to counsel bright young minds on what makes for happiness as they enter a notoriously unhappy profession.

She was not yet a justice then, or even a judge. She had no ambitions beyond teaching the law, a subject she once described as “fun” (apart from the “drudgery” of document review); beyond the satisfactions of professional service (even the meetings of the University parking committee); beyond the attractive brick home in South Bend’s Harter Heights neighborhood, the tailgate parties on football Saturdays, summer afternoons at Lake Michigan. She was, herself, quite happy.

Yet it is hard not to read her life to that point, and the unexpected professional challenges that lay around the corner, into the track-meet story, which is also unmistakably about how

to win:

A substantial scholarship takes her to a liberal arts college in Memphis. At graduation she’s honored as the most outstanding English major and writer of the most distinguished senior thesis. She’s inducted into the Rhodes College Hall of Fame by classmate acclaim.

At Notre Dame Law School, she’s editor of the law review, graduates summa cum laude, wins the Hoynes Prize for “the best record in scholarship, application, deportment and achievement.”

She lands clerkships with two legendary jurists, Laurence Silberman of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals and Justice Scalia.

Then comes a job teaching law at her alma mater, just as the Law School is hiring more alumni, more Supreme Court clerks, more women. Three times she’s voted “distinguished professor of the year.” And when the call comes sometime after that 2016 commencement speech, wondering if she’d consider serving on the federal bench, it’s hard not to imagine that chord played first when she was 10 years old resonating in Barrett’s head.

“Look straight ahead and run your best.” Winning, yes, but not as an ego or resume builder. If her uncle’s wisdom drives her, it’s as a call to perseverance through challenge, a message reinforced by her faith. “God is not served well by mediocrity,” said Father Ted Hesburgh, CSC, the late Notre Dame president who felt so strongly about forming students of all backgrounds and talents for public service.

Hesburgh’s favorite prayer, after the Mass and breviary, was “Come, Holy Spirit.” In Louisiana in the 1970s and ’80s, Mike and Linda Coney raised their six daughters and one son in a spirituality centered on the third person of the Trinity. Much was made in the news and social media last fall about the People of Praise, the Catholic and ecumenical lay movement nurtured at Notre Dame during the ’70s, about speaking in tongues as a form of prayer, about “handmaid” as a former title for the community’s women leaders — a label Mary applies to herself when addressing the angel Gabriel in the Gospel of St. Luke.

Less was said about the attributes of Spirit-led Christianity and how they help a believer navigate daily life. But Catholics study the seven “gifts” of the Holy Spirit when preparing to receive the sacrament of Confirmation — wisdom, counsel, knowledge and fortitude seem especially useful for a good lawyer. Readings from St. Paul’s letter to the Galatians remind them of the “fruits” of the Holy Spirit’s presence in the faithful Christian community: Love, joy, kindness, goodness and so on. Such ideals form the core of the vision that groups like People of Praise uphold for their members. Richard Garnett, a neighbor, friend of the Barretts and religious-freedom expert at the Law School, told the South Bend Tribune in 2018 that the family’s faith is “not so different from the lived religious experiences of millions of Americans.”

Before she left home for Rhodes in the fall of 1990, making the journey up I-55 and back many times in the family’s brown-and-orange beater, Amy Coney may have picked up other practices that would help with the duties of a motherhood and professional life she could then scarcely have envisioned. Her father, a Shell Oil attorney and deacon at Metairie’s St. Catherine of Siena parish, fretted over his sermons. “At first preparing a homily took most of Saturday,” he once wrote. “That was unfair to my family. So I asked the Lord to help me get it done in about an hour. He has honored that request.”

At Rhodes, Amy seemed likeliest to follow her mother’s footsteps. Linda Coney had taught high school French before Amy was born. Her daughter majored in English literature, adding a minor in French because she got an A- in one class, and that wouldn’t stand. As a senior, she sat in her dorm room weighing career paths. Teaching and law both promised the reading and writing she loved. Law won, she’s said, because she felt it would involve her more directly in the real world, “the shaping of society.”

Establishing justice

Politico called it “grooming” — as if a cabal of Notre Dame law professors locked in on the most promising student of their 1994 recruiting class and saw a future justice of the U.S. Supreme Court 26 years in the making.

Judge Patrick Schiltz has a different take. “To become a Supreme Court justice is like getting hit by lightning several times in a row,” he says. It’s really hard to do.

Schiltz joined the NDLS faculty in 1995 and taught Evidence to about 45 students. His first time around, he prepared exhaustively. Amy Coney showed up ready, her mind on “a different plane.” She asked at least one question in almost every class, and maybe every fourth question was so probing that her prof didn’t know the answer. He’d scribble it in the margins and promise to find out. Looking over his materials today, he says, “There’s always ‘Amy notes.’”

But here’s the thing, he says, recalling the focused 23-year-old fast becoming a stealth legend in the halls of the old Law School building. “She has an old soul about her.” Calm confidence. Generosity. Law students are competitive, anxious people by nature, says Schiltz, whose 1999 Vanderbilt Law Review article, “On Being a Happy, Healthy, and Ethical Member of an Unhappy, Unhealthy, and Unethical Profession,” was cited in The Washington Post among nine works including To Kill a Mockingbird and The Federalist Papers that every prospective law student should read. Students are “programmed to hate somebody” that good, he says. “I never heard a bad word or a snide word about Amy from any of her classmates. She was just such an obviously gracious, kind, decent person that . . . you couldn’t dislike her if you wanted to.”

Barrett came to the ideas at the core of her judicial philosophy — originalism and textualism — under no one’s influence but her own. “I think I started gravitating towards that as a first-year when I took Constitutional Criminal Procedure, and my professor was not an originalist, but that was my first exposure to constitutional cases,” she told an audience in 2019. Time and again, she agreed with originalist writings, in which she found two basic commitments — one, that the meaning of a law, whether a modern statute or the Constitution itself “is fixed as of the time it’s ratified,” and two, that this meaning prevails over others “if it’s discernible.” Sometimes legal language is open-ended, subjective, like the phrase about “unreasonable searches and seizures” in the Fourth Amendment. There, the meaning of “unreasonable” requires further deliberation. Most of the time, however, the language is clear. “That’s where the Constitution gets its authority,” she said. “We agree to live by the Constitution until it’s lawfully changed” by amendment.

“And judges can’t change it. That’s not democratic,” she said. “The Constitution isn’t the panacea that cures every societal problem. We have to trust our political branches to do that.”

John Garvey, now president of the Catholic University of America, whose First Amendment course Barrett took at Notre Dame, hired the maturing student as his research assistant. They co-wrote an article for the Marquette Law Review about the death penalty, arguing “almost exactly the opposite” of what opponents of Barrett’s two judicial nominations would claim, namely that she would infuse her religious views into her legal opinions. “We argued,” Garvey summarized in a Washington Post op-ed, “that recusal would be the appropriate course of action for a Catholic judge who felt that his or her religious beliefs were in conflict with upholding the law.”

And then Amy Coney, No. 1 in her class, took off for Washington.

Judicial power

The New York Times tells the next story. “Conservative” professors Schiltz and William Kelley did what all professors try to do for their most deserving students: They opened a door. “Judge Silberman, a Reagan appointee whose chambers typically accepted clerks from only top law schools and often recommended them to Justice Scalia, hired [their protégé] without even an interview, after Mr. Kelley had insisted she would have been the top student at Harvard, too.”

“I think I’ve always been tough. Judge Silberman definitely made me tougher,” Barrett said in an interview early last year. “He is formidable. He really can grasp issues in cases very clearly and write clearly and quickly. . . . So that was just a great experience.”

Silberman became another mentor. He would sit behind his former clerk during her 2017 hearings for the 7th Circuit job and, smiling broadly, swear her in to office at her investiture ceremony at Notre Dame. When the time came, back in 1998, for the self-described “baby lawyer” to take her next step, his recommendation to Scalia probably carried the day.

If you weren’t a textualist, clerking for Scalia didn’t make sense, says Ara Lovitt, who shared an office with Amy Coney during October Term 1998. Right or left didn’t matter so much. In fact, he notes, “there was an institution of the so-called Liberal Scalia Clerk, who agreed with his methodology but was left of center . . . just to further ensure that he wasn’t importing any politics into his legal decisions.”

The idea was, the more you open your life and give, the more you receive, the more everyone gets to do and to be.

She — again — made friends quickly. A lunchtime running group dashed down the National Mall to the Washington Monument and back. She grew closest to the three most religious of the female clerks — a Catholic, a Mormon and an Orthodox Jew — and when one of those women, Nicole Stelle Garnett, announced she was expecting, Amy Coney co-hosted a baby shower in the justices’ spouses’ dining room.

Meanwhile, she established herself as an intellectual force. “Early on in the term there was a very big administrative law case involving telecommunications policy,” Lovitt recalls. “A ton of work, super-complicated, and, you know, kind of a thankless job.” Overwhelmed, he and Scalia’s two other clerks sidestepped it. “And she took that and did a great job on it, and got an opportunity to work with clerks in all the other chambers on it. And ultimately Justice Scalia wound up writing an opinion for the majority.”

“When assigned to work on an extremely complex, difficult case, especially one involving a hard-to-comprehend statutory scheme, I would first go to Barrett to explain it to me,” Harvard’s Feldman remembers. “Then I would go to [Justice Stephen Breyer’s clerk Jenny] Martinez to tell me what I should think about it.”

Intelligence and collegiality commanded respect at the court, a tone set most notably by Ginsburg and Scalia, who crossed swords where it mattered — in their writing. In chambers, Barrett’s said of her old boss, “he didn’t want you to agree with him. He wanted you to say what you thought. And so disagreeing with him as I sometimes did and pushing back . . . with someone like Justice Scalia really taught me a lot . . . about oral advocacy and being articulate. And who better to learn how to write under than someone who was as great a writer as he was?”

Domestic “tranquility”

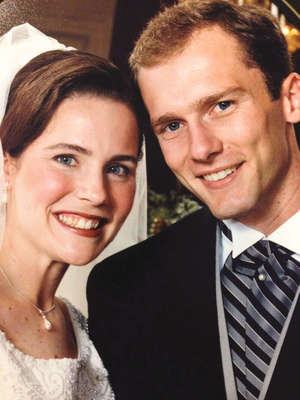

She got married. She became Amy Coney Barrett.

Jesse Barrett ’96, ’99J.D. was two years behind her at the Law School. They went to football games, shared an understanding of who they each were in relationship to God, respected each other as intellectual peers. A boyhood friend remembers Jesse, a future federal prosecutor, introducing him to Amy one night at Corby’s. He thought, “He finally met his match. She’s not going to take any of his stuff! You want the best to shine through in a good friend, and Amy does that” for Jesse.

She cut her private-practice teeth on work that included a bit part in Bush v. Gore, scored a fellowship at George Washington University that helped her explore the academic path. Then Emma was born, and the Barretts confronted a choice that many working parents face, feeling “terribly guilty” about leaving their infant daughter in day care, which they did for a time. They hoped for a big family; they had no plan. Things just unfolded, Amy would later say.

Notre Dame offered her a job in 2002, and she took it. The Barretts evaluated how things were working for them and the kids at every step. Back in South Bend, they played as a team, got intensive help from Jesse’s aunt and benefited from the conveniences of a small city where they had friends from several chapters in their lives.

They’d made the choice to adopt when Amy was pregnant with Tess. Haiti, which then encouraged overseas adoptions, appealed in part because it was close enough to visit as a child grew older. When Vivian came home to South Bend at the age of 14 months, she was malnourished, wearing clothing sized for newborns and unable to stand on her own. Years later, after Liam was born, the Barretts hoped to adopt again. Now Haiti wasn’t so open. Bureaucratic snags caused delay after delay and the couple determined to withdraw their paperwork. Then an earthquake devastated the Caribbean nation, killing hundreds of thousands of people, and the Barretts were contacted for a placement. They had just discovered they were expecting a baby girl they would name Juliet.

Amy Barrett put on her coat and walked 10 minutes in the January cold to a bench in Cedar Grove Cemetery. She contemplated what they had as a family, what a child might need. “OK,” she concluded. “If life’s really hard, at least it’s short.”

If the Rhodes College senior had chosen the law as her means to shape society, she now understood that God would ask nothing more important from her than raising children: “That’s where you have your greatest impact in the world.” A shivering John Peter soon stepped off a plane with Jesse in Chicago. And after Benjamin was born with Down syndrome, Patrick Schiltz and his wife dropped by during a visit from Minnesota to talk about their own positive experiences raising a child with Down.

The idea was, the more you open your life and give, the more you receive, the more everyone gets to do and to be. The Barretts’ backyard became a Harter Heights kid magnet. “I have filled a lot of Easter eggs with Amy Barrett,” Nicole Garnett says, laughing. The Halloween candy exchange, the Mardi Gras soiree featuring Amy’s Louisiana cooking, ordering the bouncy house for the summer block party — the Barretts were always there. So in September 2020, when Garnett, now a Notre Dame law professor, put out the call for meals, rides to school, whatever was needed, two months of slots filled up in two hours. It was Amy Coney Barrett’s It’s a Wonderful Life moment.

Closing statements

Students showed up for day one of Judge Barrett’s Statutory Interpretation seminar at Notre Dame last August having read three opinions in Bostock v. Clayton County, handed down by the Supreme Court not two months earlier. Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote for the 6-3 majority, which ruled essentially that prohibitions against discrimination “because of sex” under the 1964 Civil Rights Act extend to discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. Justices Samuel Alito and Brett Kavanaugh wrote dissents.

Barrett gave a short background lecture, then began asking questions, walking the students through the opinions. The collective task: Make the best possible arguments for and against each one. How should the statute be interpreted and applied to the facts of the case?

Barrett took a risk, says Aly Cox, setting the tone for a discussion-heavy semester with 18 third-year law students who barely knew each other by dissecting a case with “huge” political consequences, pressing them to explain which views they found most convincing. “And it never got super-heated or political,” Cox marvels. “It was just brilliant.”

It was lost on no one that the justices’ debate had taken place on textualist grounds.

Cox calls her former professor — Barrett turned the class over to colleagues when the White House called six weeks later — an intellectual role model. She says she admires what she’s read of Barrett’s scholarship, but that’s the only way you’d know what she thinks.

“She presented all sides of every argument,” says Cox’s classmate Keith Ongeri, the Student Bar Association president who supported Barrett’s nomination even though he voted for Joe Biden. “I personally am not a big believer in originalism, but a lot of my critiques of originalism are founded in what I learned from her.”

Students who took Barrett’s Evidence class all remember watching My Cousin Vinny and a stop-motion Lego video to learn about expert testimony and hearsay objections. But while the methods could be fun, the lessons were often ennobling. Alexa Baltes ’17J.D. wound up in Barrett’s first-year Constitutional Law course “by providence,” she says. “One thing that stands out to me from that class in particular is the faith in the system with which I left it.” Despite jurists’ differing politics and methods, Baltes emerged able to trust they “were engaged in law, not policymaking, and grounded their decisions in first principles rather than preferences.”

She later returned to clerk for her former professor and found that the same heart for the needs of the person in front of her had transferred from Barrett’s campus office to her chambers in downtown South Bend. She recalls the day Barrett set aside an opinion on deadline to get crutches for a clerk who’d injured his leg playing basketball. The time she invited the clerks to share a multiple-course New Orleans meal with her family. A hilariously awkward ride to the federal courthouse in Chicago: the passenger-side doors of the worn-out minivan wouldn’t open, so Barrett hustled to the driver’s side and, laughing, hopped in back, telling her clerks, “I’m good.”

“She’s exactly who you think she is,” said one of the many lawyers asked their impressions by ABA evaluators. “Honest and forthright.” “Selfless and sincere.” “Whip smart.”

“The myth,” said another, “is real.”

“What’s remarkable about Amy is, if you’re sitting outside the Law School, you have no idea what a giant this woman is in her field,” says Aimee Buccellato ’00, an associate professor of architecture whose kids attend school with Barrett’s. “But, you know, when you’re sitting in miniature chairs together, doing a kindergarten activity, she’s just a mom, being like any of the other moms.”

“Well, some people are going to say mean things about her for the rest of her life, and others will turn her into a kind of a hero. And she would probably prefer neither of those things to be the case,” says Nicole Garnett, who is bracing to miss a dear friend she’s “grown up with” as a professor and parent for 20-plus years.

“She’s like the rest of us. She’s been up all night with kids vomiting, and she’s tired and grumpy the next day. She knows what it is to have a surly teenager and a colicky baby, and, you know, the normal pressures of life. So, she’s not perfect. She’s not a saint; none of us are. But she’s pretty workable.”

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.