An intriguing, 1,100-word article arrived in early winter, unsolicited, from William Anderson ’67:

Back when I attended Notre Dame during the 1960s, one of the most visible and beloved professors was Anton-Hermann Chroust. This German émigré first came to ND in 1946 and retired in 1972. He may well have been the foremost scholar on the faculty. He had degrees in history and philosophy from German universities as well as a law degree from Harvard. He is said to have authored more than 200 articles and books ranging from the lost dialogues of Aristotle to the rise of the legal profession in America. He taught classes in both the history and philosophy departments as well as the law school.

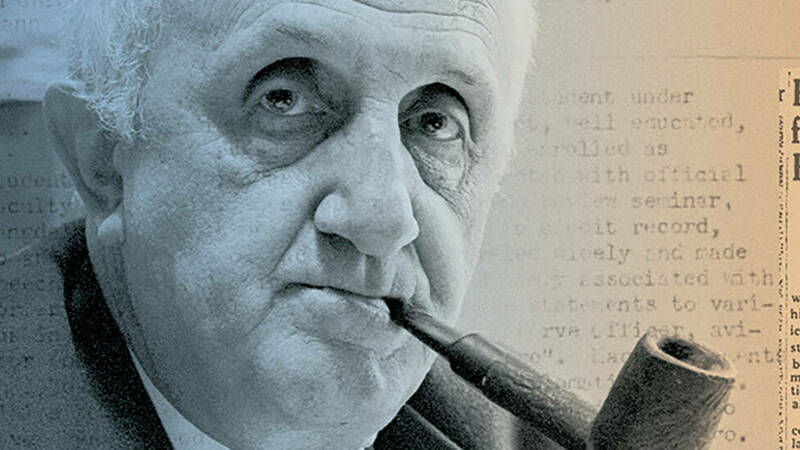

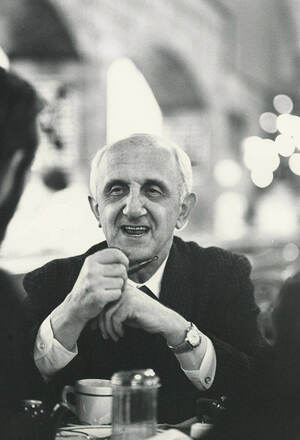

Most every day this pipe-smoking, somewhat rumpled figure would be found in the public cafeteria in the South Dining Hall. There he would hold court not only with other faculty members, but he welcomed any undergraduate who came by. He was intelligent, irreverent and topical. A curmudgeon, he often criticized both the college administration and the Church. In class he once remarked that only the Catholic Church and the Nazis thought schoolchildren should be required to wear uniforms.

Most students admired him — even those he did not teach; everyone knew him as the professor who tooled around campus in his red Mercedes sports car. On The University of Notre Dame Class of 1969 Blog, Tim Swan ’69, ’72J.D. characterized him as our Mr. Chips and called him “the most interesting person I ever met at Notre Dame.” In the popular mystery novels ND philosophy professor Ralph McInerny authored, one will find numerous positive references to “Tony Chroust.”

But a different and disturbing image of Chroust had recently emerged, Anderson wrote: that of a possible Nazi operative before and during the Second World War, as alleged by a new book on the history of Harvard Law School.

Such suspicions deserved further investigation if Notre Dame Magazine were to tell the story. What might archives, personal papers, government documents, vital records and newspapers reveal about the nature of the relationship a prominent and revered Notre Dame professor once had with the Nazis?

The book about Harvard included a chapter about its famed law dean Roscoe Pound, long suspected to have been a Nazi sympathizer, and his lengthy and close friendship with Chroust. The two men met when Chroust arrived in the United States from his native Germany in 1932 at age 25 to study for a law degree at Harvard. Their relationship, and Pound’s extensive efforts to protect and help Chroust, played out over the next several decades — including time during World War II that the immigrant scholar spent in U.S. custody.

Chroust is remembered today as a German American jurist, philosopher, author and historian. From August 1946 until his retirement, he was a professor of law, philosophy and history at Notre Dame. He died in 1982.

Photos in old Dome yearbooks capture Chroust lecturing to a Notre Dame Law School class and chatting with students and colleagues over coffee at the former public cafeteria — the “Pay Caf” — in South Dining Hall. In some pictures, he has a pipe clamped between his teeth, the perfect image of a mid-20th century American university professor.

As Anderson indicated, Chroust was best known for his 1965 book, The Rise of the Legal Profession in America, two books on Aristotle and almost 200 articles. He also authored Socrates, Man and Myth, a critical analysis of attempts to reconstruct a historical and philosophical image of Socrates from the few, and sometimes contradictory, existing sources about the Greek philosopher’s life.

“All we really know for sure about Socrates is his parents’ names, the year he was born and the year he died. The rest is mere conjecture,” Chroust said in a 1979 interview in The Observer.

The Socratic problem is an apt metaphor for Chroust’s own life and career. Based on surviving documents, he was a mystery, a gifted man with a dubious past and conflicting loyalties, a teller of colorful stories — and of outright lies.

He often spoke proudly of being a member of Germany’s gold-medal winning water polo team at the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam. And there was a mysterious spouse, a woman who never visited South Bend.

What is known about Chroust? What is truth and what is myth? And what falls into the dark crevices in between? At the very least, his story offers an example of how a life and one’s association with a movement may leave starkly different impressions when assessed at different points in time.

Arrival in the U. S.

Anton-Hermann Chroust was born on January 28, 1907, in the small Bavarian city of Würzburg, Germany. He was the son of Anton Julius Chroust, an Austrian-born professor of German history at the University of Würzburg, and Johanna Chroust. The family was Catholic.

In September 1932, the brilliant young student arrived in New York aboard the SS Deutschland. He was heading to Boston, where he had a scholarship to attend Harvard Law School. Chroust had earned a bachelor’s degree from Würzburg in 1925, a law degree from the University of Erlangen in 1929 and a doctorate from the University of Munich in 1931.

As an established scholar, he soon met the man who would become his mentor and defender. The dean of Harvard Law School from 1916 to ’36, Nathan Roscoe Pound was an internationally renowned educator and one of the most cited legal scholars of the 20th century, according to The Journal of Legal Studies. He also had a reputation as a Nazi sympathizer. He visited Germany several times during the 1930s and accepted an honorary degree from the University of Berlin in 1934, after Adolf Hitler had become chancellor of Germany.

Chroust finished his academic work at Harvard in 1933, earning a doctorate in juridical science, Harvard’s most advanced law degree. The following May, according to FBI files, he traveled to Germany for about six months, then returned to the U.S. that November and began to look for academic jobs. Meanwhile, he served as a special assistant to Pound, a role that would continue until 1941.

Meeting with Nazis

Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany in January 1933. Under his leadership, the NSDAP — the Nazi Party — began dismantling the nation’s democratic system. Legislation passed that year suspended individual rights and due process of law. New policies severely limited the number of Jewish children who could attend public schools, while books deemed “non-German” were burned throughout the country. By March, the Nazis had opened the first concentration camp at Dachau. Many American academics and intellectuals condemned the swift growth of state-sponsored anti-Semitism in Germany.

The following summer, from June 30 to July 2, 1934, Hitler ordered a series of political executions designed to consolidate his power. At least 85 people, possibly hundreds more, were murdered during the “Night of the Long Knives,” also called the “Blood Purge.”

Two days later, according to research by Boston-based attorney Peter Rees in a 2019 article published in the Boston College Law Review, Pound and his wife arrived in France to begin their summer vacation in Europe. Pound recorded details of their trip in his diary, which today is on file in Harvard’s archives. On July 10, the couple arrived in Oberammergau in southern Bavaria and attended the town’s historic passion play, the Passionsspiele, a dramatic — and, at the time, highly anti-Semitic — depiction of the life and death of Jesus Christ. That afternoon, Pound wrote, they had lunch with an acquaintance identified as “Dr. Chroust.”

The following day, the Pounds traveled to Munich. Pound’s diary records a lunch meeting with Hans Frank, the Bavarian minister for justice, Edmund Mezger, a University of Munich law professor, and Walter Luetgebrune, vice president of the Akademie für Deutsches Recht, the Academy for German Law. That evening, the Pounds, escorted by Chroust and another young lawyer named Josef Bühler, attended a Wagner opera as Frank’s guests. “Great day,” Pound wrote.

On July 12, Pound visited the University of Munich and delivered a speech, then attended a tea at Mezger’s home. Chroust was again among the guests.

These men, all members of the Akademie, were no ordinary lawyers. They were prominent Nazis, and three later were convicted of war crimes.

On the morning of December 9, 1941 — two days after the Pearl Harbor attack that led to America’s entry into the Second World War — FBI agents arrived at Chroust’s rooming house in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and took him into custody, charging him as a dangerous enemy alien.

Frank became Hitler’s personal attorney and governor-general of occupied Poland. In 1946 he was convicted at the Nuremberg Tribunal for mass murder and executed. Mezger worked for Heinrich Himmler, a mastermind of the Holocaust, and was sentenced to prison after the war. Bühler was among participants in the 1942 Wannsee Conference at which senior Nazi leaders agreed on a “final solution” — the planned genocide of all Jews. In 1948, he was found guilty of crimes against humanity and executed.

The Akademie provided legal reasoning and research to support Nazi policies, Rees explains in his article. Among its goals was the establishment of relationships with foreign legal scholars. Rees cites a German Foreign Office report, dated June 1934, that describes Harvard’s law dean as someone who had long been favorably disposed toward Germany and its culture — and its ascendant politics. He had, for instance, spoken out against a Jewish-led boycott of German goods in the United States.

“I would like to point out that a very significant portion of the leading men in the current [U.S.] government emerged from Harvard Law School, and their character continues to have a certain close personal connection with the Law School and its Dean,” a translation of the report states. “The favorable repercussions that a suitable honor would exert on Dean Pound cannot be overlooked.”

The report further suggests that Anton-Hermann Chroust could be helpful in arranging Pound’s activities in Germany because of their friendship. However, nothing that has surfaced in the files of Germany’s Foreign Office states that Chroust was acting as an official agent of the Nazi government.

During Pound’s European sojourn, Austria’s chancellor was assassinated in a Nazi coup, and Hitler became Führer of Germany. Before returning home, Pound gave an interview to the Paris Herald, published on August 4, 1934. He told the newspaper he was “everywhere impressed by the absence of tension and by the peaceful manner in which the people accepted Hitler as their leader.”

Six weeks later, back in Boston, Pound publicly accepted an honorary degree from the University of Berlin, presented in a ceremony on the Harvard campus by the German ambassador to the United States. Pound’s acceptance of the honor, Rees writes, was widely seen as a statement of support for the Nazi government. Harvard University President James Conant attended the ceremony, but refused to be photographed with Pound and the German officials.

Pound would again visit Germany in the summers of 1936 and ’37, after the adoption of the Nuremberg Laws that stripped Jews of their German citizenship. Chroust met or accompanied Pound during each of these trips.

Allegations and arrest

Back at Harvard, Chroust was beginning to attract attention for his behavior and statements about his involvement in events in Germany, even as he pursued academic appointments at American universities. The FBI opened a file on Chroust in 1935 and watched him over the next six years.

Support for Germany and admiration of the Nazis was not uncommon in 1930s America. Immigrants of German ancestry and their descendants made up the nation’s largest ethnic group. Although pride in German ancestry and support for German culture had languished during and after the First World War, many American cities still had German-language newspapers, social clubs and neighborhoods where the language was widely spoken.

At least one organization sought to convert such heartfelt ties to the German homeland into open support for the Nazis and the rise of fascism in Europe. The Amerikadeutscher Volksbund — the German American Bund — was created in New York in 1936 as “an organization of patriotic Americans of German stock.” Members urged U.S. isolationism and the specific avoidance of European conflicts.

The Bund operated about 20 youth and family training camps, and eventually grew to a membership of at least 25,000 people in 70 regional chapters across the country. Camp participants wore Nazi uniforms, gave the Nazi salute and engaged in weapons training and other quasi-military activities. At an “Americanization” rally held at Madison Square Garden on February 20, 1939, the Bund drew 20,000 Nazi supporters to hear speakers denounce Jewish conspiracies as well as President Franklin D. Roosevelt and other American figures. An enormous portrait of Washington hung above the stage, alongside swastika banners. Outside, police officers tried to keep the peace among huge crowds of rally protesters.

Meanwhile, Father Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest based in Royal Oak, Michigan, was fanning the flames of anti-Semitism through weekly radio broadcasts that reached tens of millions of listeners. Coughlin’s largest following was in Boston, where listeners often heeded his criticisms of Jews and his calls to boycott Jewish goods.

His Indiana death certificate also claims he was a member of the U.S. armed forces. And in the box listing marital status, the word “widowed” is crossed out, and the phrase “never married” typed above. But Chroust had married.

In such a cultural environment, Chroust’s position at Harvard would have been conspicuous. The nature of his work as Pound’s “special assistant” was never clear, write historians Bruce Kimball and Daniel Coquillette, the authors of The Intellectual Sword: Harvard Law School, the Second Century. No extant document establishes an official appointment at the law school. But according to archival records, Chroust had an office, conducted research and taught a weekly seminar as part of Pound’s classes. He filed a military draft registration form, required at the time of foreign nationals living in the U.S., and listed Pound as his employer.

World War II began on September 1, 1939, with the German invasion of Poland. That fall, the Bund fell apart, its leader was arrested for embezzlement and tax evasion and many of its assets were seized. As late as May 1940 — after the German invasions of the Netherlands, Belgium and France — a Gallup poll indicated that 93 percent of Americans opposed entering the war against Germany.

On the morning of December 9, 1941 — two days after the Pearl Harbor attack that led to America’s entry into the Second World War — FBI agents arrived at Chroust’s rooming house in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and took him into custody, charging him as a dangerous enemy alien.

Serious allegations had been made against Chroust, according to recently declassified FBI records obtained by Peter Rees. The federal government’s case lists at least 14 different informants, including members of the Harvard faculty. Records state Chroust, during his early years at Harvard, had bragged to neighbors and others about his membership in the NSDAP and his various assignments, even claiming to be a Gauleiter, or district governor, an officer in the Nazi stormtroopers and a German army reservist.

Witnesses said he further claimed to have visited Cuba, Belgium, Mexico City and Texas on Nazi business and reported on New England Germans who were critical of the Nazis. That he had boasted of his connections with the Ministry for Propaganda in Berlin. That he had flaunted his collection of Nazi uniforms and once gave a pro-Nazi speech at a Christmas party. That he claimed a friendship with Hitler and acquaintance with Hermann Göring and Rudolf Hess.

“While Doctor Chroust has professed an anti-Nazi attitude in recent years, there is convincing evidence in the files of this Department to show that he was at one time a member of the Nazi Party and that in the years prior to 1936, he was an intellectual apologist and propagandist for Hitler and the Nazis,” U.S. Attorney General Thomas C. Clark wrote in 1945, rejecting a request to change Chroust’s status at that time as an enemy alien parolee.

“This evidence leads irresistibly to the conclusion that at least until 1936 Dr. Chroust, who is admittedly a brilliant and learned man, was also a whole-hearted Nazi and had been entrusted by the Nazi government with an important mission in this country. There is, however, some evidence tending to show that beginning in 1936 Dr. Chroust experienced a change of heart and became an anti-Nazi. . . . The question in the case, therefore, is whether Dr. Chroust’s expressed anti-Nazi position subsequent to 1936 was genuine or whether his reformation was insincere and brought about by some motive other than allegiance to democratic principles,” Clark wrote.

Records in Germany identify him as a member of the Nazi party as late as July 15, 1939. Clark said his office had evidence that Chroust “remained a paid up member of the Nazi Party” until 1941.

Before he was detained in 1941, Chroust had failed to apply for an extension of his visa beyond April 3 of that year, which meant he was living in the U.S. in violation of the law. Federal authorities soon began deportation proceedings.

Chroust had traveled widely in the U.S. during his Harvard years, including a 1938 road trip to the West Coast, The Boston Daily Globe reported in 1942.

The Globe story described Pound’s efforts to intercede on Chroust’s behalf. Pound told the newspaper that his protégé hoped to join the U.S. Army and had started paperwork to become a citizen. He told an Alien Enemy Hearing Board “that, whether [Chroust] was a Nazi or not, he would still keep him under his wing as a student,” Kimball and Coquillette write in The Intellectual Sword.

Pound had stepped down as dean in 1936 but remained on Harvard’s law faculty for another 13 years. He wrote many letters on Chroust’s behalf to members of Congress and other government officials, trying to clear Chroust’s name. In March 1943, Chroust was released on parole with Pound designated to serve as his parole sponsor. When Chroust was detained a second time in 1945, Pound again sought his release.

Through all of this, Pound never disclosed his 1934 meeting with high-level Nazis in Munich or mentioned that Chroust was present. Kimball and Coquillette argue that Pound may even have perjured himself by providing an alibi for Chroust during the Night of the Long Knives, claiming the young German was with him and his wife at the time. “Pound’s omission and falsehood appear to constitute serious ethical and professional transgressions and even a criminal offense because they were written to a federal official, the U.S. attorney general,” the authors conclude.

Among Pound’s papers at the Harvard Law Library are letters he wrote in the late 1930s and early ’40s recommending Chroust’s hiring to top administrators at more than a dozen American universities, including Michigan, Texas, Arizona, Drake and the University of Puerto Rico. Some of these letters make vague references to Chroust’s purported political difficulties in his home country because of his Catholic faith.

“Chroust is not the type of man who shrinks from getting out of school and into the world,” Pound assured a professor at Iowa State. “On the contrary, he has knocked about the world a good deal and in particular has run about the greater part of this country in an automobile looking at men and things.”

The war in Europe ended in May 1945. Meanwhile, Pound continued writing letters to acquaintances across the country, recommending Chroust for a faculty position “without reservation.”

Chroust was released on parole a second time on February 23, 1946, but he was again facing possible deportation, according to correspondence in Pound’s papers. Six months later, he joined the Notre Dame faculty.

Pound had connections at Notre Dame and had been to campus several times. He presented guest lectures each year from 1942 to ’45, according to reports in The Notre Dame Scholastic.

In July 1946, Chroust wrote a letter to the former dean’s secretary at Harvard, saying he was being offered a position at Notre Dame. “But in order to clinch the job I will have to submit a letter of recommendation from Dean Pound — so I am told,” he wrote. Pound was out of the country. Chroust asked if it was possible to find a copy of a 1945 recommendation to the University of Denver and mail it to Notre Dame.

That letter recommended Chroust’s hiring “without reservation” and sought to separate him from any affiliation with the Nazis. “He studied under some of the most important jurists in the German Universities as they were before the Hitler regime,” Pound wrote. Chroust “is an exceptionally fine fellow personally. He speaks and writes English as though it were his native tongue.”

“The effect of Pound’s letter was something stunning,” Chroust later told the secretary. Upon receiving it, Rev. Howard Kenna, CSC, Notre Dame’s director of studies, had sent a telegram inviting him to South Bend for an interview.

On September 26, Chroust wrote to thank Pound, noting how helpful his secretary had been. “This letter won me my present position, that is an associate professorship in law.”

A copy of the letter sent in Pound’s name remains in Chroust’s files in the University Archives, as do recommendations written in 1946 by two other men affiliated with Harvard, W.J. Batz and Professor Arthur von Mehren.

It remains unknown what information Chroust provided Notre Dame when he applied for the job, or whether University officials were aware of his time in U.S. custody during the war. His files do not include a 1946 curriculum vitae or resume.

Chroust became a U.S. citizen in South Bend on February 7, 1951, with Pound serving as his sponsor. A photograph from the ceremony was published in the South Bend Tribune. Pound had remained at Harvard until 1949, when he moved to the UCLA School of Law. He later returned to Cambridge, where died in 1964 at age 93.

A popular professor

Chroust settled readily into his life at Notre Dame. In 1952, he was among 65 members of the faculty who signed their names to large advertisements in newspapers across the country endorsing Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson, a Democrat, in his campaign for president.

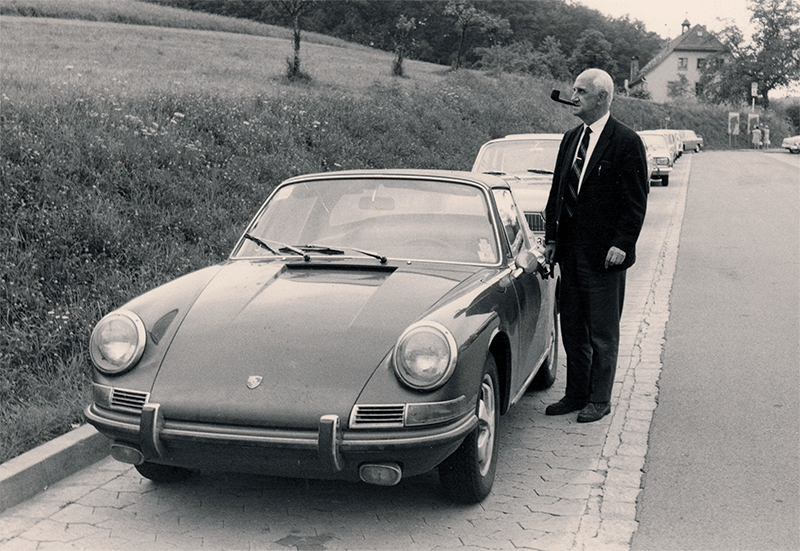

He became a kind of campus celebrity, driving around in his Mercedes Benz 300SL, which he later replaced with a red 1967 Porsche 911S Targa. In his later years, he spent May to October traveling and studying in Europe. He’d ship his car to Europe and back so he could drive himself.

Students in the University’s Innsbruck Program in 1967 recall hearing the growl of a sports car coming up the mountain to their residence. The visitor was Chroust, driving his new Porsche.

Back in South Bend, Ed Fitzpatrick ’69, ’70MME, ’74J.D., who at the time drove a Ford Fairlane, recalls Chroust challenging him to a drag race.

Fitzpatrick shares another memory: “After one class, I was confused about a certain item so I went up to his desk and said, ‘Professor, I am afraid that I didn’t quite understand what you said about such and such. It seemed kind of Greek to me.’ He said, ‘OK, let’s have a look in my notebook. Yup, you are right, it is Greek,’ and he held up his notebook for me to read and everything in it was written in Greek.”

Chroust continued to teach part time in retirement. He died of natural causes on January 11, 1982, at his South Bend home. He was 74. He is buried in Cedar Grove Cemetery.

“He wore his erudition easily and comfortably, like a pair of shoes; he had not a trace of pomposity,” the Notre Dame Lawyer eulogized. In his will, he left money to fund scholarships for law students: one at Harvard, one at Yale and five at Notre Dame.

Chroust’s obituary in the South Bend Tribune erroneously stated he was a World War II veteran. His Indiana death certificate also claims he was a member of the U.S. armed forces. And in the box listing marital status, the word “widowed” is crossed out, and the phrase “never married” typed above.

But Chroust had married. His engagement to Elisabeth Redmond of Brookline, Massachusetts, was announced in the June 13, 1937, edition of The Boston Daily Globe. Redmond, then age 23 and a Boston native, had attended the Winsor School and later spent several years traveling abroad. Chroust “is at present a research fellow at the Harvard Law School,” the announcement stated.

The two had met in May 1934, when the German battle cruiser Karlsruhe visited Boston during a “goodwill tour” designed to bolster support abroad for the Nazi government. Redmond, who had visited Germany several times and spoke German, was invited by a family friend, Baron Kurt von Tippelskirch, the German consul at Boston, to help entertain the visiting officers. She met Chroust at a dance, according to a letter her mother wrote to Pound many years later.

They were married March 29, 1941, by a justice of the peace in Rockland, Massachusetts. Less than nine months later, Chroust was taken into custody. They separated in 1946, and Elisabeth Chroust remained in Boston and never moved to South Bend. The couple had no children. Their divorce was finalized in 1950 in St. Joseph County, Indiana. Neither remarried.

In her 2002 book, Loyal Sons & Daughters: A Notre Dame Memoir, Sister Jean Lenz, OFM, ’67M.A. recalled meeting Chroust and occasionally stopping to listen to his reminiscences during gatherings in the Pay Caf. Chroust was famous for his definition of history, the beloved former rector and administrator wrote: “the rhythmic repetition of human stupidity down through the contingency of time.”

One evening, Chroust recounted a deeply personal story. “He told me about his young wife who met with a tragic accident while horseback riding. She lingered for some time with severe head injuries. They were hard days for Professor Chroust,” Lenz wrote.

Elisabeth Redmond Chroust was a skilled horsewoman in her youth. Her triumphs in horse shows received notice in The Boston Daily Globe. She was knocked unconscious in 1933 during a riding accident in Weimar, Germany, her mother had once told Pound. But Elisabeth died in 1961 at age 47 in a hospital in Braintree, Massachusetts, from complications of cancer and tuberculosis. At that point, she and Anton-Hermann Chroust had been divorced for more than a decade.

An enigma

Two years after he published his law review article, Peter Rees says he’s not sure if Chroust was an official Nazi agent. “I think my article raises a lot more questions,” he says, “than it provides answers.”

That brings us back to William Anderson’s essay.

Saved from deportation, Chroust came to Notre Dame in 1946. What is unknown is how much ND knew of Chroust’s controversial past. It is possible Pound’s recommendation and Chroust’s denials along with his brilliant mind convinced the school to overlook the past accusations. It remains difficult for me, and I assume for many former students, to reconcile the man we knew with his past. At the very least he was a member of the Nazi Party before the war; at worst he was a Nazi spy. The latter claim appears to lack credibility.

The most damning evidence against him are the statements he made to Harvard faculty and friends. There is little corroborative proof backing up these assertions. Some, such as the claim that he had saved Hitler’s life, stretch the limits of credulity. It is likely, in a perverted way, Chroust created stories for his colleagues to make himself appear more important. It would not be the only time he acted in this manner; many years later, in the 1960s, Chroust would boast to his students that he had won a gold medal in water polo for Germany in the Olympics of 1928. When he passed in 1982, the student newspaper, The Observer, had a short obituary that included mention of his gold medal.

The internet age has made the truth easier to uncover. Germany did win its only gold medal for water polo in Amsterdam in 1928. The official records of the games list the German team members by name; Chroust’s is missing. Some find old habits are difficult to break — but better to be remembered as a teller of tall tales than as a Nazi agent.

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine. William Anderson is a professor emeritus of history at Suffolk Community College in New York and author of The Price of Liberty: The Public Debt of the American Revolution.