In the heat of a July afternoon during the throes of the pandemic, my backyard serves as a location for a virtual hearing of the Family Division of the Circuit Court for Montgomery County, Maryland. After postponements since May due to COVID-19, the case became one of the court’s first held online.

My clients are a 36-year-old woman and her 20-year-old daughter. They are from El Salvador. Neither of them has legal status in the United States. Our case pertained to the possibility of the daughter attaining a Special Immigrant Juvenile classification under the Immigration and Nationality Act — a path to eventual U.S. citizenship. For a child under age 21 to be granted that status, the law requires proof of abuse, abandonment or neglect that prevents them from returning home.

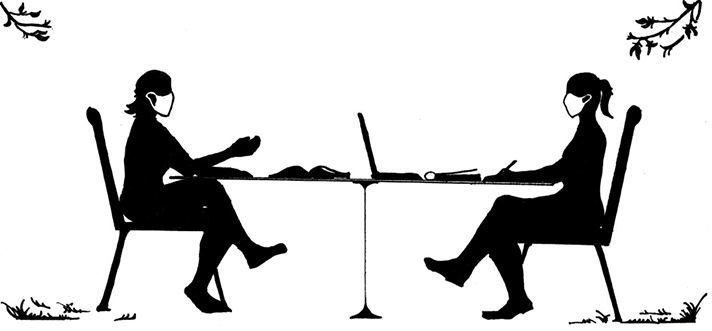

I doubted that mother, daughter and myself could maintain the social distance necessary in my small home office. The covered patio in my backyard would be the best alternative. A six-foot table was set up with chairs at both ends. I felt that we were being prudent and compliant.

Admitting original documents for the court record was one of my concerns about the circumstances. The certified birth certificate for the daughter and original IDs would normally be presented at the hearing. But the court modified its process to allow for scanned IDs and accepted the copy of the birth certificate attached to the pleading filed in February. The court’s creative flexibility has been critically important to the administration of justice.

Language was another potential issue. Neither mother nor daughter are fluent in English, but the administrative assistant for the magistrate assured me that the interpreter we had requested would participate in the call from the courtroom.

Since I do not speak Spanish, the patience and effort of volunteer translators is essential to the conduct of these cases. One person in particular has assisted me with several clients far beyond her immediate responsibility as an interpreter, such as driving them to meetings when their rides have fallen through. When one client went to the wrong courthouse the morning of a hearing, it was this translator who took the initiative and went out of her way to clear up the confusion. There were only minutes to spare when the client arrived before a failed court appearance would have forced a continuance.

The federal statute provides for a two-part legal process. The first part requires an adult, in their local state court, to obtain an order of custody for the unaccompanied child and approval of factual findings to permit the minor’s application for Special Immigrant Juvenile status. When these two orders have been granted, the child, who must be under 21 years old and unmarried, can pursue the second part of the process before the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. My role has been to file the complaint for custody and motion for factual findings in the circuit court.

It takes courage for my clients and their children to come to the United States without legal status. It’s an act of bravery for parents who lack such protections to sign petitions and appear in court on behalf of their children. To my knowledge, immigration authorities have never made an arrest inside the local circuit court. Still, I have seen fear in the eyes of many young mothers who understand that they’re risking removal from the country so that her child might someday become a U.S. citizen.

During the online hearing, there is feedback noise from more than one device being connected at a time. We continue the hearing with only one device connected.

Both mother and daughter are very anxious to obtain these court orders because the daughter will age out of the statutory requirement of being under age 21 within a few weeks. The daughter, along with her disabled older sister, had been raised for several years by her aging grandparents. Both girls had been neglected and abandoned by their father from early childhood.

The daughter had been living in fear not only of the generalized gang violence in El Salvador, but the very real experience of being extorted and threatened to become a “girlfriend” of the gang. There was no one who could protect her from this violence in El Salvador.

The unusual proceeding ends well for mother and daughter — the proposed orders are granted. Two very happy people leave my backyard that afternoon. A third happy person stays.

Two weeks later, a Guatemalan family of four — a mother and her three children — join me for another socially distanced outdoor teleconference hearing. All four had suffered emotional and physical abuse at the hands of the father. The mother describes his rage when he sliced off part of her finger with a machete.

Tears spill as the judge grants the requested judicial orders for all three children.

As a pro bono attorney with various organizations assisting young people in obtaining Special Immigrant Juvenile status, I am gratified that all my clients, from various countries, have obtained the orders we requested. This work has given me much joy — and ample compensation in hugs, smiles and happy tears.

Maureen Power Wilkerson has represented minors pro bono for five years as an adjunct to her estates and trusts practice.