What does the future hold for the religiously faithful in the United States, a nation in which the “nones” — those with no religious affiliation — now count as the largest “religious” group?

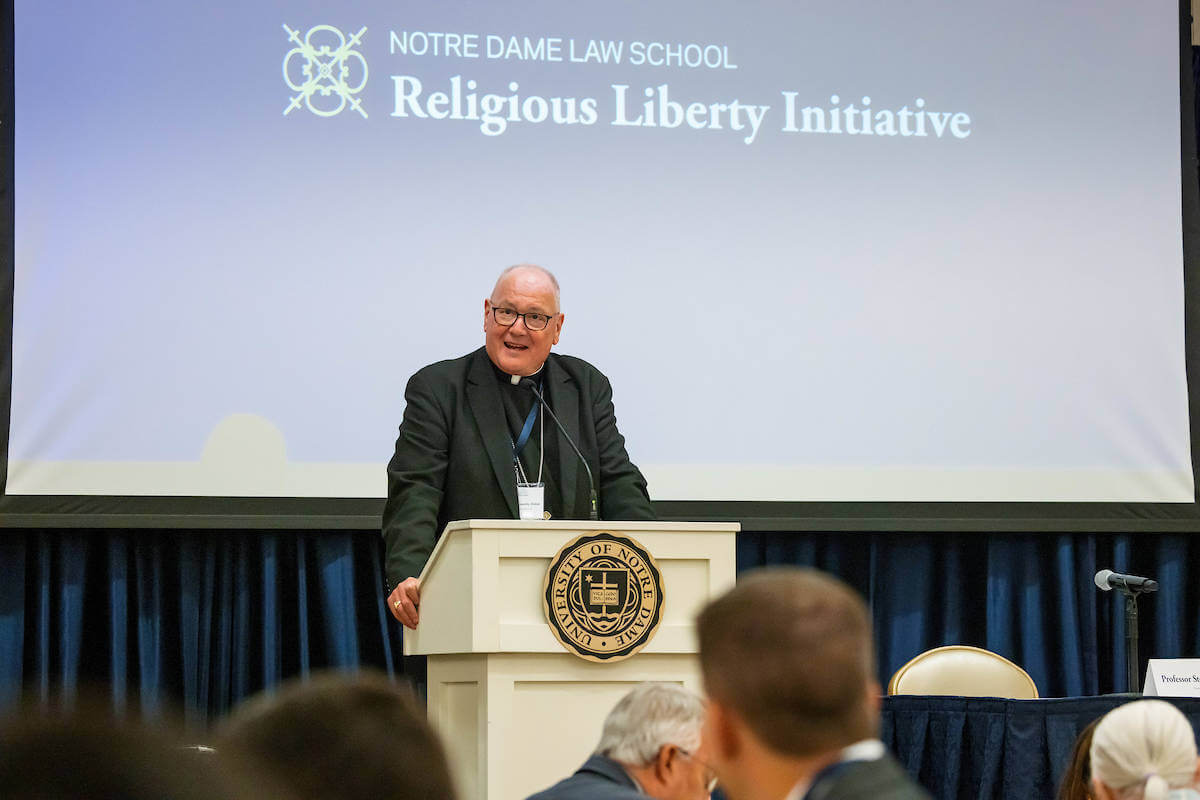

Four faith leaders addressed the contemporary quest for religious freedom in American society at an interfaith dialogue panel on campus June 28 as part of Notre Dame Law School’s inaugural Religious Liberty Summit.

Cardinal Timothy Dolan, Catholic archbishop of New York, gave a keynote address, then joined the panel discussion that also included: Jacqueline Rivers, executive director of The Seymour Institute for Black Church and Policy Studies; Elder Quentin Cook, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, a governing body of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; and Rabbi Meir Soloveichik, an orthodox rabbi who leads Congregation Shearith Israel in New York, the oldest Jewish congregation in the U.S. (Soloveichik spoke remotely via video.)

Following are selections from the panelists.

Cardinal Timothy Dolan:

What used to be a rather non-controversial no-brainer — defending religious freedom, something as American as mom, apple pie, the flag and Knute Rockne — has now become caricatured, I’m afraid, as an oppressive, partisan, right wing, unenlightened crusade.

I vigorously defend our first and most cherished liberty, not because I’m a believer, but because I’m a citizen. I defended it not to boost the Church, but to boost the human rights tradition at the heart of our republic.

Religious freedom is enshrined not to protect the government from religion, but religion from the government. The Baptists in Rhode Island, the Quakers in Pennsylvania, the Congregationalists in Massachusetts and the tiny Catholic minority in Maryland during the colonial years, they didn’t want any favors from the government. These groups just wanted basically to be left alone, left alone to exercise their faith, to worship as they had been raised and to follow their properly formed consciences in the public square.

Elder Quentin Cook:

Accountability to God for our relationships with each other is a powerful force for good and strongly supports democracy. Being accountable sustains and blesses the values that are most important for societal unity.

My plea today is that all religions work together to defend faith and religious freedom in a manner that protects people of diverse faiths, as well as those of no faith. Catholics, evangelicals, Jews, Muslims, Latter-day Saints and other faiths must be part of a coalition of faiths that succor, act as a sanctuary and promulgate religious freedom across the world.

Jacqueline Rivers:

Religion was one of the central claims that Southern planters made to defend slavery, and they acted on what they claimed were their religious beliefs. Now since we all believe that there is one God, and since we believe he speaks to our consciences, one has to wonder whether they actually believed what they claimed. But that was a claim they made, that they were acting on deeply held religious beliefs, which were massively disadvantageous to enslaved black Africans.

(Black Christians) have powerful, active, passionate outpourings of faith, yet on the issue of religious freedom, we are the sleeping giant. Because we have seen many conservative Christians, not just white evangelicals, use their faith as a means to discriminate against Black people.

Rabbi Meir Soloveichik:

We as Jews seek to be neighbors. We seek to be fully part of the society in which we find ourselves, but we also demand — first and foremost — that we will (retain) the right to be strangers, set apart by our faith and by our principles.

Even as aspects of our own age have indicated that the going might indeed get tough nevertheless, in the process, we communities of faith have also found each other. And that, at least, is something to celebrate.

The Law School last year established the Religious Liberty Initiative, which promotes religious freedom around the world for people of all faiths.

Nury Turkel, a noted Uyghur-American attorney and human rights activist was honored at the summit with the first Notre Dame Prize for Religious Liberty.

Turkel was born in 1970, during the Cultural Revolution, in a re-education camp in western China. His mother had been detained when she was six months pregnant, while his father, a professor, was taken to a separate forced labor camp.

The family was taken into custody because they are Uyghurs, a recognized ethnic minority group in China that practices the Muslim faith. More than a million Uyghurs have been detained in internment camps in China and subjected to abuse, forced labor and indoctrination, according to the U.S. State Department.

Turkel earned his law degree at American University. Last year, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi appointed Turkel to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom.

Religious freedom is a hallmark issue for G. Marcus Cole, the Joseph A. Matson Dean and Professor of Law. “I want people all around the world to look to Notre Dame for help when their religious liberty is being encroached upon or they’re being oppressed because of their faith — or lack of faith,” Cole said in a 2020 interview in Notre Dame Magazine.

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine.