I

The Via dei Giubbonari is a narrow pedestrian street in Rome, used by Italians, pilgrims and tourists alike. At its midpoint the crowd parts: Half the people turn downhill to take the footbridge over the Tiber to Trastevere, and the other half keep going straight, toward the streetcar stop and Largo Argentina, a transfer point for city buses. This means that the quarter bounded by the two routes, the streetcar tracks and the river is more or less untouched by tourism.

So it was when I was there last spring, anyhow. Walking toward the streetcar, I tended right for a change, hoping to find a half-remembered shop with watchbands in the window. After many trips to Rome, I like to think I know the area pretty well: the church of Trinità dei Pellegrini where the Latin Mass devotees go, the timeworn osteria without a name, the parking garage with its Italian term, Autorimessa spelled out in elegant script. Soon I found myself in streets where I’d walked before but never attentively. Here was a small piazza full of compact cars parked bumper to bumper. I went through it almost on tiptoe, and as I did, I noticed a plaque on a wall that recorded in Italian that this was the place where the Apostle Paul had stayed when in Rome.

A standard-issue Baroque church named for the saint was boarded up for renovations. For the moment, the plaque alone marked the spot.

Paul — here? In this unspectacular place? In a city that has made the marking of sacred history through elegant monuments both a religion and an art, it didn’t seem possible. Joni Mitchell’s line about paving paradise and putting up a parking lot came to mind. I was amazed, and a little aggrieved, on Paul’s behalf; I felt solidarity with the saint whose name I carry around.

II

Amazed because if there’s any figure whose stature in Rome would seem assured, it is Paul, right? He is thought of as Christianity’s second founder. It was Paul who brought Christianity to the Gentiles (through the efforts recounted in the Acts of the Apostles); it was Paul who brought Gentiles to Christianity (through his letters to small communities of would-be believers near and far). Those epistles are the source for some of the best-known sayings in Western civilization: a man reaps what he sows; the letter killeth, but the spirit giveth life; for now we see through a glass darkly, but then we shall see face to face, and so on. Paul’s theology was the basis for the Reformation, prompted when Luther pondered the Church in light of Paul’s assertion, drawn from Habbakuk, that “The just shall live by faith.” Four centuries later, his theology was the wellspring for the crisis theology of Karl Barth; in the next generation, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, captured by the Nazis and accused of taking part in a plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler, modeled his Letters and Papers from Prison on the letters Paul wrote from prison. Two decades later, Martin Luther King Jr. did likewise with his Letter from Birmingham Jail. Accused of extremism, King replied that, like Paul, he was “an extremist for the Christian gospel.”

Pablo Picasso, Pablo Casals, Paul McCartney and Paul Hewson (aka Bono) carry Paul’s name. Three recent popes have called themselves Paul in whole or part. I’ve long figured that my own name is a consequence of that: On September 8, 1965, the Vatican announced that Pope Paul VI would travel to New York City — the first pope to visit the New World. I was born the next day and was baptized Paul a few days later.

Now I was in the place where Paul had spent time with the Romans to whom he had written his Letter to the Romans — about two years, spent under house arrest. It’s owing to Paul’s efforts as much as Peter’s that the Church thrived in this part of the world and wound up becoming Roman Catholicism. How, in history-conscious Rome, could Paul’s part of the city be overlooked like this?

III

Of course, Paul is amply represented elsewhere in Rome — entombed at the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls; knocked off his horse by a lightning-flash of faith in the Caravaggio painting at Santa Maria del Popolo; lauded on June 29, when the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul marks the start of summer in Italy.

But the neglect I saw that day was suggestive. Paul, it seems to me, has receded in importance within Catholicism. The stature of second founder has passed to St. Francis of Assisi, especially since Jorge Mario Bergoglio took his name in 2013 upon his election to the papacy.

I know I have lost touch with Paul. And I know that’s not right. So I’m going to try to get back in touch with him the way he kept in touch with his disciples: through a short, loosely organized piece of writing.

IV

Like so many cradle Catholics, I grew up hearing parts of Paul’s letters read aloud at Mass and reading those same parts in the newsprint-and-staple missalette, a paragraph or three at a time.

It wasn’t till my early 20s that I looked into Paul in earnest. Out of college, suddenly a 9-to-6 office worker in Manhattan, living in a skeletally furnished apartment uptown, lacking a circle of friends or a clear sense of what was next, I began a kind of independent study in Christianity, puzzling out the religion to which I’d always belonged and trying to grasp my place in it.

The sites of this haphazard undertaking were the museums, secondhand bookshops and churches of the city, which in those days were open throughout the day for individual devotion.

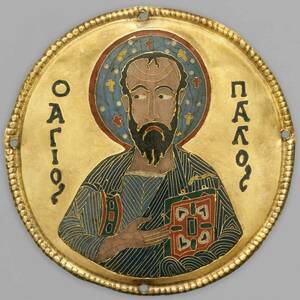

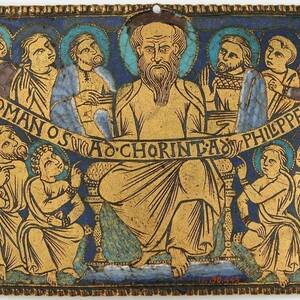

Sundays, I would go to Mass at one of the grand churches on the Upper East Side, buy a hot dog from the vendor outside the Metropolitan Museum, lunch in four bites on the steps, and go in. I usually went first to the catacomb-like rooms where the art of the early Middle Ages was on display: reliquaries, patens, ivories, roundels. A glass case held a set of gold medallions, like baseball cards of the early Christians. I peered in. There was Paul: bald, bearded, wrinkle-browed, haloed, his eyes cast unnaturally to his right, as if supervising Peter. And there, too, was Paul at the center of the disciples on an enamel plaque from Becket-era England: hair, beard, brow and eyes etched in time-defying detail. I bent and met my reflection in the glass.

V

Although I didn’t know it, the diminishment of Paul was already well advanced.

The earliest known Christian writing is his: a letter he sent to Christians in Thessalonica in about A.D. 50. The 13 letters associated with Paul make up more than half the New Testament, but scholarship has altered his profile. Since 1943, when Pope Pius XII lifted some restrictions on Catholic biblical studies, and after Vatican II especially, the use of historical-critical methods has upended the common understanding of the New Testament and the early Church.

Many of us know those developments through the stress on “the historical Jesus.” This Jesus is distinctly Jewish and only partly aware of a calling to die and rise again. He is seen one way in the synoptic gospels (Mark, Luke and Matthew, based on the same main source), a different way in the Gospel of John, and variously in the gnostic and apocryphal texts.

The Catholic scholars who sought the historical Jesus proposed that more precise knowledge of this figure would bring us closer to him and him to us. That was my experience. Lucid distillations of the scholarship — Cullen Murphy’s 1986 cover story in The Atlantic is still a favorite — prompted a quickening of curiosity and a deepening of faith. “Basically the Christian message is He Himself,” the Swiss theologian Hans Küng told Murphy, and the fresh scholarship — Jesus, for example, if a typical Near Eastern man of his time, would have been about 5-foot-4; yet about his appearance “the Gospels say not one word” — made Jesus vivid and enigmatic at once.

Inevitably, those scholarly methods diminished the role of Paul. For one thing, they sought to “get back” to the Jesus of history as he was before he was cloaked in Pauline theology, which is centered on the risen Christ known through faith. For another, they trimmed the Pauline canon. Only seven of the 13 letters are now seen as “authentically” composed by Paul: Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians and Philemon. Ephesians is seen as “deutero-Pauline” and “possibly pseudonymous” — it’s either a work of joint authorship or one written wholly by somebody else. So is Colossians (“Here there cannot be Greek and Jew, circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave, free man, but Christ is all, and in all”). So is 2 Thessalonians (“For even when we were with you, this we commanded you, that if any would not work, neither should he eat”). Titus and 1 and 2 Timothy (“I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith”) were probably written by others. Hebrews surely was.

This change in the understanding of the epistles is not a loss per se. It bolsters the view that the first Christian teachings reflect the convictions of a community more than the predilections of a single author. Seen as works of many hands, the letters are actually more authoritative records of early Christian belief than they were before. But there’s no question that Paul has been shrunken somewhat.

VI

During the same period, the Christian communities in those places where Paul had traveled were also greatly diminished. William Dalrymple, in From the Holy Mountain (1997), explains: “In the east of Turkey, the Syrian Orthodox Church is virtually extinct, its ancient monasteries either empty or in the process of being evacuated. . . . In Lebanon, the Maronites have now effectively lost the long civil war, and their stranglehold on political power has finally been broken. Most Maronites today live abroad, in exile. The same is true of the Palestinian Christians a little to the south: nearly half a century after the creation of the State of Israel, fewer Palestinian Christians now remain in Palestine than live outside it . . . the remaining Christians in Jerusalem could be flown out in just nine jumbo jets.” Also in this period, Paul’s authority as the progenitor of Church-centered Christianity has been forcefully challenged.

Reading C.S. Lewis’ The Four Loves during my haphazard independent study, I was astonished to find this most tradition-loving of modern Christian writers dismissing Paul. Jesus, Lewis declared approvingly, “hardly ever gave a straight answer to a straight question. He will not be, in the way we want, ‘pinned down.’” Lewis went on: “Descending lower, we find a somewhat similar difficulty with St. Paul. I cannot be the only reader who has wondered why God, having given him so many gifts, withheld from him (what would to us seem so necessary for the first Christian theologian) that of lucidity and orderly exposition.”

Today Paul’s exposition of Christianity is seen by some as the source of all that’s wrong with Christianity. It’s as if he left a series of stumbling blocks that the Church has to get past: Wives, submit to your husbands; men, take no thought of sex, lest you be impure when Christ comes in judgment; fornicators, beware! His declaration that Christians should “be subject to the governing authorities” blunted Jesus’ challenge to the social order; his counsel that a disciple should treat an enslaved man kindly — but not free him — became a proof-text for the justification of slavery.

Elaine Pagels, in Adam, Eve, and the Serpent (1988), made Paul and then Augustine the villains of early Christianity. More puritanical than Jesus himself, “Jesus’ zealous disciple Paul” had led even married men to shun sex because in his account sexual relations would distract them from the urgent work of proclaiming the Gospel before the end of the world in Christ’s second coming; Augustine had made the dread of sex the linchpin of his theology, reverse-engineering Christian thought so that it could be seen as going all the way back to the fall of Adam due to the seductions of Eve. And the rest, Pagels argued, was history.

A Jesuit I knew warned me off Adam, Eve, and the Serpent the way one of his forebears might have told me to keep clear of Lady Chatterly’s Lover. In its place he recommended Henry Chadwick’s The Early Church, and I bought the Penguin paperback edition. The cover, taken from an early-medieval British piece in the Victoria and Albert Museum, showed Paul in dispute with Jews and Greeks in Damascus. It is an arresting image. He is bald and bearded but in action: eyes fixed on his disputants, lips turned down in vexation, right hand extended to assert a point, the forefinger bent so that it nearly meets the bent forefinger of his antagonist.

That Paul was Paul for me for decades. I now have a better idea why: It turns out that the Paul on the cover of Chadwick’s book and the Paul in the Met came from the same workshop. No wonder the image of Paul as an angry, middle-aged man took hold of me with documentary authority.

How did the bald-and-bandy-legged guy I saw in the glass case at the Met stir things up so much? Through intensity of belief, that’s how.

VII

That Paul is a true believer: a man who knows what he believes, who regards the power, vividness and exception-rejecting clarity of his beliefs as evidence of their veracity, and who is determined to see to it that the men he is talking with end up believing the way he does.

Of course, that’s not all he was. Paul was a Hellenic Jew — one educated in Greek. As Jesus was a carpenter, so Paul was a tent maker. And he was a missionary. An introduction to the New Testament lightly used by one of my sons in college describes him as a shopkeeper: He “evidently did not preach on the street corner or stage evangelistic rallies, and he did not . . . begin by preaching in the local synagogue. He instead started up a business in town and talked to his customers, convincing them to accept the Christian message.” But whatever else he was, he was a true believer first and last. Prior to his conversion from Judaism, this aspect of his character led him to deride the Church and join in the persecution of it; afterward, it emboldened him to speak and write ardently straight through to his martyrdom in Rome.

How did the bald-and-bandy-legged guy I saw in the glass case at the Met stir things up so much? Through intensity of belief, that’s how.

And that, when I get down to it, I think, is why he feels remote to me today. He is remote because I want him to be. In our time, the true believer is the progenitor of so much that strikes me as overdone, unsound, misguided, dangerous; and many of the true believers among us give a bad name to those of ages past — and to Catholicism, to religion itself.

As I see it, so much in the life of the believer — about human origins, about the ways God is met and known, about the claims of the Church, about the sheer variety and superabundance and kinship and contradictoriness of the religious traditions, about the body and sex and love and fidelity, about violence and suffering — calls for reflection from a state of principled uncertainty. In this, true-believing is a stumbling block. The true believer is distant because I am keeping my distance.

VIII

And yet there is another Paul in the letters we call his. This Paul is “the least of the apostles,” the adult convert, the unsystematic believer working up a theology via correspondence, the anti-rigorist stressing the spirit of the law.

IX

A few years ago at Powell’s, a new-and-used bookstore in Portland, Oregon, I decided to reacquire some books I had read in childhood. Robin Lee Graham’s The Boy Who Sailed Around the World Alone. Rocky Bleier’s Fighting Back. Mary Stewart’s The Crystal Cave. And Good News for Modern Man — the New Testament that was stocked in bulk in our parish, with a cover featuring the banners of foreign newspapers. Back in New York, I put Good News on the shelf alongside the Revised Standard Version, the New Jerusalem Bible, Monsignor Ronald Knox’s New Testament in English, Tyndale’s New Testament and La Santa Bibbia, and forgot about it.

I took it out not long ago. The corners are curled. The copyright page has the imprimatur of Richard Cardinal Cushing, Archbishop of Boston, March 7, 1966. The text is illustrated with line drawings of key episodes, in a style I now recognize as a cross between Matisse’s late, single-line images and the “Don’t Litter” signage in the national parks. “Paul’s Letter to the Romans” begins on page 339.

I read the first two chapters, marking them with another vestige of my childhood: a Dixon Ticonderoga pencil. It was as if I was reading Paul for the first time. This Paul is a communicator, and the epistle is his means of communication.

So much is communicated in those two chapters. There’s the narrative of salvation and Paul’s place in it. There’s a tender greeting to the Christians in Rome. And there’s an account of “The Power of the Gospel” (the Good News subhead calls it this) as succinct and winning as anyone has ever made. Paul tells us: “For I have complete confidence in the gospel: it is God’s power to save all who believe, first the Jews and also the Gentiles. For the gospel reveals how God puts men right with himself: it is through faith alone, from beginning to end. As the scripture says, ‘He who is put right with God through faith shall live.’”

That “put right” is just right, so much more so than the “made righteous” of other translations; it at once captures the not-rightness of sin (like a broken bone that needs to be put right) and offsets the apodictic certitude of “faith alone.”

Paul roots “faith alone” in a prosecutorial account of human waywardness. His feature exhibit is homosexuality: “the men give up natural sexual relations with women and burn with passion for each other. Men do shameful things with each other, and as a result they receive in themselves the punishment they deserve for their wrongdoing.” During the AIDS epidemic, this passage was cited often in regard to homosexual acts. (Pat Buchanan, a presidential candidate in 1988 — and a Catholic — said Paulishly: “The homosexuals have declared war on nature, and now nature is exacting an awful retribution.”) Here again is Paul the true believer, rendering judgment on those whose beliefs are not fully his.

X

So Chapter Two is an about-face. “Do you, my friend, pass judgment on others?” Paul asks. He doesn’t wait for an answer. “You have no excuse at all, whoever you are. For when you judge others, but do the same things that they do, you condemn yourself.”

The point is more plain-spoken and commonsensical than I remembered it. I found reasons for this, shelved side by side in my workspace. Different translators have rendered the passage variously. In his New Testament, Knox, the brilliant English radio priest and friend of literary converts like Evelyn Waugh, put it this way: “So, friend, if thou canst see thy neighbor’s faults, no excuse is left thee, whoever thou art; in blaming him, thou dost own thyself guilty, since thou, for all thy blame, livest the same life as he.” The New Jerusalem Bible’s version has a bony simplicity: “So no matter who you are, if you pass judgment you have no excuse. It is yourself that you condemn when you judge others, since you behave in the same way as those you are condemning.” A recent translation by the Orthodox polymath David Bentley Hart is wierdly fusty: “So you are without defense, O man — everyone who judges — for in that you judge another you condemn yourself; because you who judge engage in the same practices.”

XI

The passage about hypocrisy goes to the root of Paul. For Paul, more than anybody else in the history of Christianity, judged others in a way that wound up condemning himself. He judged the first followers of Jesus, taking a role in stoning St. Stephen to death, and his about-face from Judaism to Christianity was so abrupt and dramatic that he became Western civilization’s archetype of the convert, the twice-born, the born-again.

XII

The Conversion of St. Paul is that Caravaggio painting in the church of Santa María del Popolo. It depicts the moment when Saul, en route to Damascus, is knocked to the ground and startled by a voice — the voice of Christ — who asks, “Saul, Saul, why have you been persecuting me?”

The church stands on a vast piazza where rallies take place, and to go there is to hear echoes of the hurly-burly of Roman public life when Paul was in the city, noisily making his case for Christ. The painting, from 1601, is paired with Caravaggio’s Crucifixion of St. Peter in a side chapel. The pairing is visual: Peter, aged and gray-bearded, shirtless, arms outthrust, is nailed to a cross that tilts downward from upper left to lower right. Paul, shirtless, arms outthrust, has been thrown off a horse so that he tilts downward from left to right. And the pairing is thematic: Conversion will end in crucifixion; crucifixion will be a conversion through death to eternal life.

What’s striking is where the paintings diverge. Where Peter is aged, bald and bearded, Paul is young, dark-haired and clean-shaven. This painting is the only image of young-man Paul that I know, and Paul’s youth brings out aspects of his character that I’ve overlooked all these years. Seeing it, I see Paul differently.

XIII

Why? Let’s see. Paul was born in A.D. 5, joined the persecution of Stephen in 32 and was converted on the road to Damascus in 34 — when he was 29 years old. A person of 29 isn’t an especially young person. But he is distinctly younger than the bald-and-bearded Paul who has stood pointing a finger in my soul all these years. Such a person is the age of Binx Bolling in Walker Percy’s novel The Moviegoer — a man at the end of a long coming of age.

Three years after that about-face on the road to Damascus, Paul was jailed in the city for stirring things up, but he escaped by hiding in a basket that was passed over the city wall. The scene shown on the reliquary that made such an impression on me took place soon after, in A.D. 37. So, the Paul in that episode would have been 32 — much younger than the bald, bearded, beady-eyed figure who is shown jabbing a finger at his interlocutors. No elder, Paul at the time was roughly the age of the Dante who sets out in the middle of the road of his life with the right way lost.

This Paul was also a new believer. He had turned to Christ about a thousand days earlier. The strong faith that was his most distinctive trait must have been roiling in him, convulsing him, brimming over. His is the ardor of a discoverer, a trial-and-error type whose experiment has led to an uncontrolled reaction.

XIV

Christian belief was itself new just then. Jesus had died on the cross maybe four years before. Not until 10 years later were the disciples first called “Christians,” as Acts laconically records. Not till three years after that would Paul, at age 45, write the first of his surviving letters. Only in A.D. 57 would he write the one to the Romans, which, as the longest and most strenuous of the letters, is placed first among the New Testament epistles. That is, the summation of Paul’s thought is presented as an introduction to it, the end of the journey as the beginning. Where he wound up is where we are asked to start.

The newness of Paul’s belief likely made him keenly aware of how vulnerable were these new believers to whom he addressed his letters. Doubt, slackening, scruples, a confusion of the law with the spirit, works with faith: The conflicts he stresses as vexing the groups of believers in Thessalonica and Corinth and Galatia were conflicts he knew firsthand. He was further along in faith than they were, but he and they alike were new adherents to a new religion in a way that those of us raised in societies with a Christian dimension will never be.

As it was for Paul in the first century, so it is for us in the 21st. We come from a robust tradition but find ourselves in a world made new, and we’re working things out as we go.

XV

All this in turn helps to explain the scattered and often chaotic character of Paul’s approach — the qualities that C.S. Lewis grumbled about. Paul was a man in a hurry. He was also an improviser — working through ideas with his listeners, sometimes preaching them all night and then dictating them on the fly to a companion, who did his best to capture the quicksilver qualities of Paul’s thought. His isn’t a do-it-yourself religion of the kind Flannery O’Connor saw in the postwar deep South and sought to render in her fiction, but it comes close.

I can identify with that approach. It’s not unlike the haphazard independent study in Christianity I undertook after college. But to put it that way is to miss the point.

The point is that Paul’s account of Christian belief has probably meant so much to so many people through the ages precisely because of his independence and haphazardness. What makes Paul’s sense of things credible is not that it has the authority of the second founder and true believer, but that it has the searching urgency of the new believer, who has been knocked sideways by an experience of Christ and is left to figure what it means and why it matters.

In this sense, Paul is less a second founder than a first precursor. For so many of us, Christian belief is a fitful and ongoing conversion. As it was for Paul in the first century, so it is for us in the 21st. We come from a robust tradition but find ourselves in a world made new, and we’re working things out as we go.

XVI

In Rome again a few weeks ago, I returned to the quarter near the river where Paul stayed when he was in Rome. It was even more desolate than I remembered. It was late October, and at 5:30 p.m. the streets were dark. It was not hard to imagine how dark the area must have been 2,000 years ago, when once the sun had set, torches and candles were the only sources of light.

I came to a church whose façade touted the life and works of a saint I’d never heard of: César de Bus, a Provençal of the 16th century. The door was open. I went in, figuring I’d say a prayer in the empty church, as I often do in Rome.

The church was not empty. Maybe a dozen men sat in the pews, singly or in pairs, facing the altar. Some had prayer books open in their laps. No one made a sound. The men, most of them, were brown-skinned. It was a gathering of believers such as I’d never seen in Catholic Rome.

Drowsy, I took a seat and began to form words in a prayerlike shape. . . .

I awoke to the sound of a bell. This was probably the night office; the men had assembled for the ancient rite. One man was leading it; I couldn’t tell which one. It was in Italian. That I could tell. Slowly but confidently, the men moved through the rubric of prayers, alternating responses: those on the left, those on the right, those on the left, and so on. I grasped words here and there. “Deo.” “Signore.” “Grazie.” “Aiutaci.” Help us.

This church, these men, this nameless, unsupervised, unregulated service: It felt like a new thing. For a moment I saw and heard something like what the people of this part of Rome must have seen and heard when Christian believers first settled there. It was new — and yet it was something other than new. The words were those of Catholic communal prayer, words that had been prayed in this church, in this neighborhood, in this city, more or less continuously for a couple thousand years. No doubt some of the words were Paul’s.

Paul Elie is a senior fellow in Georgetown University’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs and a regular contributor to The New Yorker. He is the author of The Life You Save May Be Your Own and Reinventing Bach.