Dunn with R&B singer Usher, right, and legendary TV producer Norman Lear in a 2015 event in Lear’s honor at Morehouse College. Photos provided

Dunn with R&B singer Usher, right, and legendary TV producer Norman Lear in a 2015 event in Lear’s honor at Morehouse College. Photos provided

Stephane Dunn ’94 M.A., ’00MFA, ’00 Ph.D., has always savored reading. Her parents kept books around her childhood home in Elkhart, Indiana, and she frequently visited the public library with her older sister. She’s still in contact with her now-88-year-old sixth-grade teacher, who encouraged her to write and create skits in class, and also with her high school English teacher Mrs. Poe, who let Dunn borrow books from her classroom library. Dunn thanks both teachers in the acknowledgments of her 2022 young-adult novel, Snitchers.

Dunn also credits the “undeclared storytellers” of her life — her aunties, mother and grandmother — whose knack for oral history and affinity for language inspired Dunn from a young age to fall in love with nontraditional narrative forms. “That was such a colorful tapestry of voices — the way they talked, reminisced about down South. . . . Their voices are accents that have remained imprinted on my imagination,” she says.

Notre Dame was a part of Dunn’s life even before she enrolled as a graduate student. In high school, she spent several summers on campus in the Upward Bound program, which helps low-income and first-generation students prepare for college, and she has fond memories of catching lightning bugs with her cousins at her grandmother’s house on the corner of Sorin and St. Peter streets.

She attended the University of Evansville in southern Indiana as an undergraduate. During Dunn’s first semester in grad school, however, she felt lost in the classroom. Surrounded by white, mostly affluent students, Dunn doubted she belonged.

Her only Black professor, the late Erskine Peters, noticed her struggle. An expert in African American literature, Peters had written African Openings to the Tree of Life, an acclaimed book about African religion, folklore, symbol and ritual that helped Dunn understand her experience as a Black student in a predominantly white space. The two formed a connection.

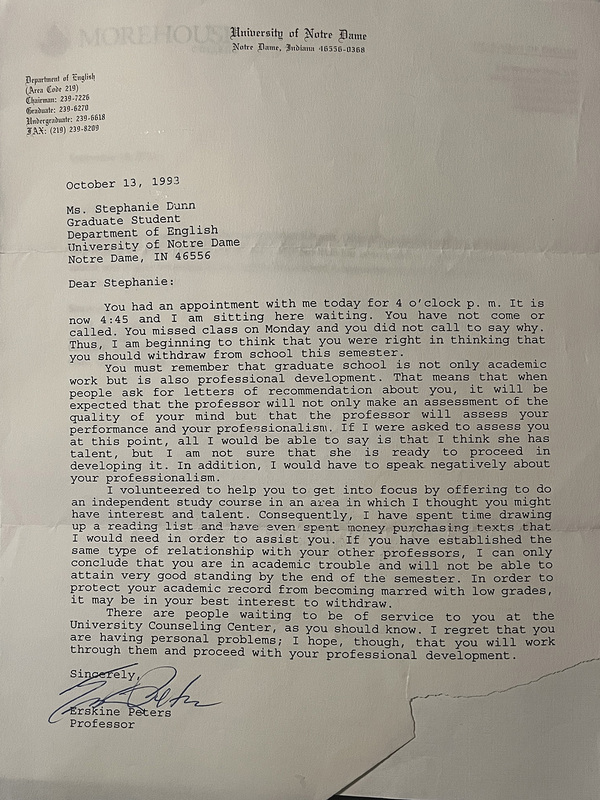

Peters became her adviser, scheduling a meeting with Dunn to review her academic plan. When she failed to show up, he wrote her a letter. The gist: I’m here waiting for you. You are bright and intelligent, but you are not stepping up.

“It’s my prized possession from graduate school, that letter,” says Dunn, who keeps it on her desk.

The motivation Peters helped her find has propelled Dunn in multiple academic and creative pursuits, including co-founding the Cinema, Television and Emerging Media Studies Program at Morehouse College, where she is a professor. A scholar of race, class and gender in American and African culture, particularly in film, TV and literature, she has co-written two short documentaries, Fight for Hope and Mr. Creek’s Move, and a number of plays.

A common thread has been grappling with violence. When police brutality and racially motivated violence became more visible over the last decade, Dunn wrote pieces for Ebony and Ms. magazines, and for The Elkhart Truth, recounting her and others’ encounters with these issues, including that of a childhood friend who was murdered while waiting to pick up her son from school. Another friend was shot to death at age 22. In the Ms. piece, Dunn draws parallels between her mother’s and aunt’s experiences with domestic violence and the case against former NFL player Ray Rice.

Snitchers was a product of years of meditation on violence. The novel follows protagonist Nia Barnes, a soon-to-be high schooler in a small Midwestern city coping with the murder of her father, who was shot in the middle of the night with no witnesses. Violence consumes Nia’s life, and her obsession with true crime and detective novels inspires her to try to find the murderer.

“I really did need to pour into something, to deal with my own angst over it,” Dunn says, “but I still wanted to remain hopeful in the midst of it all. I’m raising a Black son.”

Dunn has found that teenagers, especially those who grow up in harsh circumstances, think deeply about violence. Many of them must “thread through violence” every day, whether on their commutes to school or within their own neighborhoods or households. Dunn brought that mindset to Snitchers.

She argues books are essential for teenagers’ psychological development and the expansion of their worldviews. In light of current national conversations about censorship, Dunn notes how texts such as the autobiographies of Malcom X, Maya Angelou, Angela Davis, Frederick Douglass and Richard Wright express the liberation that can come from literacy. To exclude books, especially when most students need encouragement to read at all, is dangerous.

“Books are the doorway to imagination, but also to the development of literacy and being able to critically think. There’s a lot on the line with censorship. It’s the way we can access other lives, other people, other cultures,” Dunn says. “It really does alarm and scare me, because I don’t know where I’d be if I had not read early on.”

Dunn cites the books that shaped her, and they are diverse in content and authorship: Judy Blume’s Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret. Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie series.

“What do I really have in common with The Grapes of Wrath?” Dunn says. “But it spoke to me, the humanity of it, and lives I would have never thought about at all.”

Allie Griffith is the alumni editor of this magazine.